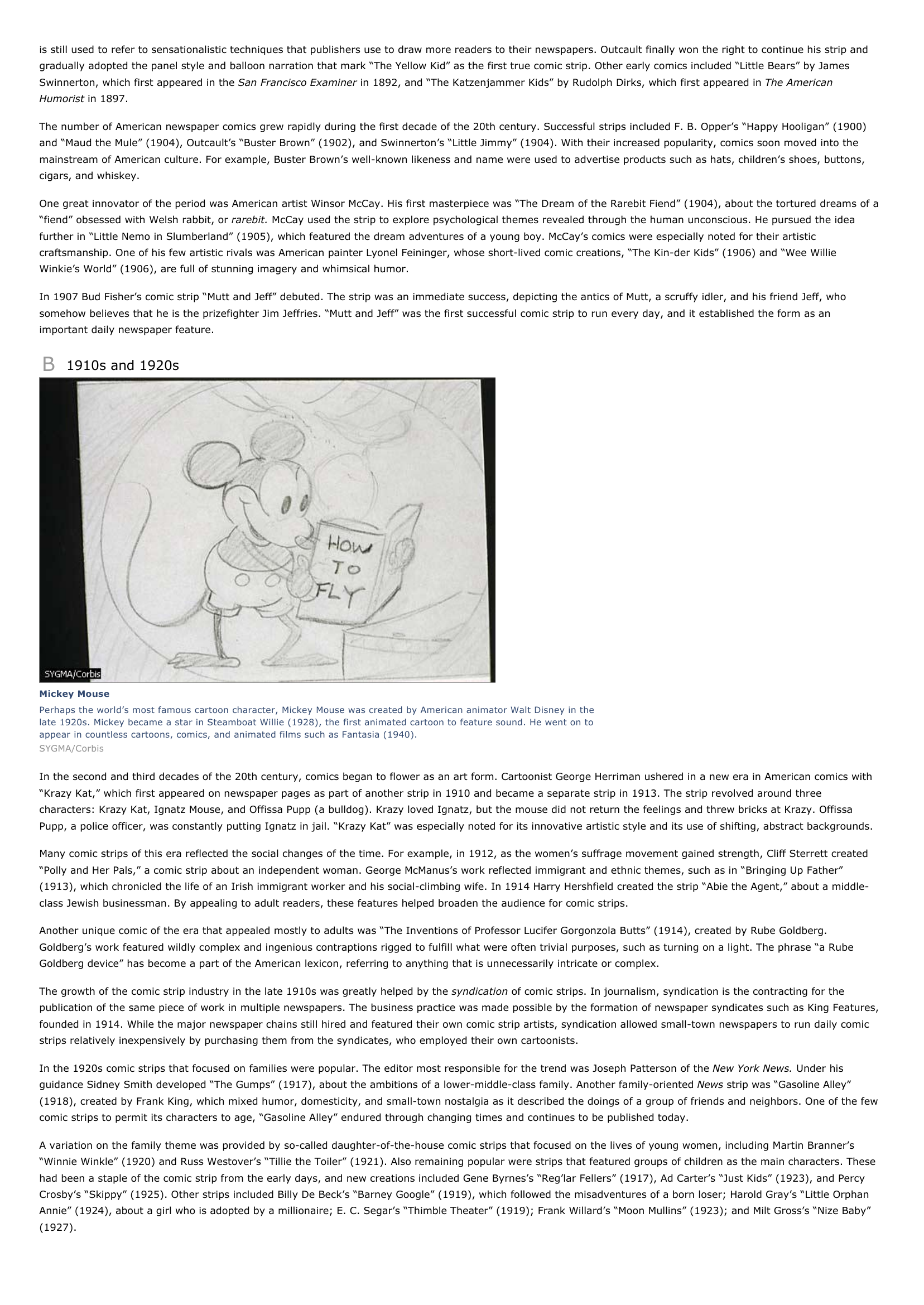

Comics I INTRODUCTION Comics, series of drawings arranged to tell a story. Most comics also include some text, which appears as dialogue or captions. Comics typically feature a continuing cast of characters. The term comics comes from the first examples of the form, which were all humorous. While many comics remain focused on humor, others involve politics, human interest, suspense, adventure, or serious treatments of relationships. In their most basic form, comics consist of simple line drawings rendering characters and scenes. They share common roots with the cartoon, a term that encompasses single-panel gag and editorial drawings as well as hand-drawn illustrations and advertisements. Comics are also related to animation, which is defined as motion pictures created by recording a series of still images, often drawings. Animated television shows and movies, sometimes called cartoon animation, are extremely popular. Many times the most popular comics are animated for TV or movies, or turned into live-action shows and motion pictures. Newspaper comics, also called comic strips, typically appear in three or four square-shaped cells, called panels. The panels are arranged in a row and are read from left to right, like text. Comic books are booklet-length comics that are more stylized and tell a more involved story. They can be written in the same style as comic strips, but they also often feature panels of different shapes and sizes and are read both horizontally and vertically. Most daily newspaper comics are published six days a week in black and white, while those on Sunday tend to be in color. Most comic books are produced in color. In the early 20th century, comics were accused of glorifying unsavory characters and thus encouraging children to misbehave. They were also condemned as being a waste of time. For several decades this view remained common. But in the 1960s people began to reevaluate comics and appreciate their artistic qualities. International comics conferences were organized, major art exhibitions devoted attention to comics, and comic art museums were founded. Comics are now regarded as one of the most significant forms of 20th-century culture. II ORIGINS The historical roots of the comics appear in the work of English artists of the 18th and 19th centuries, notably George Cruikshank, James Gillray, William Hogarth, and Thomas Rowlandson. These artists told stories by using sequences of pictures, each of which was known as a cartoon. They also made extensive use of the balloon, a white space issuing from the lips of the characters that held the words that the characters were saying. Perhaps the best examples of early balloon technique appeared in Rowlandson's cartoons, which he used to make social commentary. One of his major works featured a character named Dr. Syntax who traveled to different places and made observations about people and customs. Some of the techniques employed by the English cartoonists spread to other European countries. The most popular European comic artists of the time included Rodolphe Töppfer of Switzerland, whose Histoires en Estampes (1846-1847; Stories in Etchings) reveal an unusual ability to tell stories through pictures; Wilhelm Busch of Germany, whose "Max und Moritz" (1865) earned him great fame; and Christophe of France, author of "La Famille Fenouillard" (1889; "The Fenouillard Family"). III NEWSPAPER COMIC STRIPS The art of cartooning developed in the United States throughout the 19th century, galvanizing public opinion about important political issues of the day and even playing a pivotal role in elections. American cartoonists such as Thomas Nast, Joseph Keppler, and Bernard Gillam became very influential during this period. Towards the end of the century, comic strips, originally referred to as funnies, first appeared in the Sunday supplements of major newspapers. Newspaper publishers William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer were competing furiously for readers during this time, and they quickly saw comic strips as a valuable feature to attract more readers. A Late 1800s and Early 1900s Mutt and Jeff Mutt and Jeff first appeared as Mr. A. Mutt in a November 1907 issue of the San Francisco Chronicle. Bud Fisher's comic strip subsequently was introduced to a wide audience by newly formed newspaper syndicates, and it became the first successful daily comic strip in the United States. To satisfy demand, newspapers published collections of the cartoons, and a 1911 Mutt and Jeff collection was one of the first comic books to be published. THE BETTMANN ARCHIVE The first successful American comic strip was "The Yellow Kid," drawn by Richard Outcault. The main character of the strip initially appeared in Outcault's earlier cartoon series, "Hogan's Alley," first published in 1895 in Pulitzer's New York World. Outcault set the action of "Hogan's Alley" among squalid city tenements and backyards filled with dogs and cats, tough characters, and ragamuffins. One of the street urchins was a bald-headed child dressed in a long, dirty nightshirt. Outcault used the nightshirt as a place to make comments relating to the subject of the cartoon, and the printers, experimenting with yellow ink, chose the nightshirt as a test area. The yellow was a success, and so was the Yellow Kid, as the public dubbed the character. In 1896 Hearst hired Outcault away from the World, and Outcault began drawing "The Yellow Kid" series for Hearst's New York Journal. However, the World kept "Hogan's Alley," and the struggle between the two newspapers over the publication rights to the Yellow Kid character gave rise to the term yellow journalism. This term is still used to refer to sensationalistic techniques that publishers use to draw more readers to their newspapers. Outcault finally won the right to continue his strip and gradually adopted the panel style and balloon narration that mark "The Yellow Kid" as the first true comic strip. Other early comics included "Little Bears" by James Swinnerton, which first appeared in the San Francisco Examiner in 1892, and "The Katzenjammer Kids" by Rudolph Dirks, which first appeared in The American Humorist in 1897. The number of American newspaper comics grew rapidly during the first decade of the 20th century. Successful strips included F. B. Opper's "Happy Hooligan" (1900) and "Maud the Mule" (1904), Outcault's "Buster Brown" (1902), and Swinnerton's "Little Jimmy" (1904). With their increased popularity, comics soon moved into the mainstream of American culture. For example, Buster Brown's well-known likeness and name were used to advertise products such as hats, children's shoes, buttons, cigars, and whiskey. One great innovator of the period was American artist Winsor McCay. His first masterpiece was "The Dream of the Rarebit Fiend" (1904), about the tortured dreams of a "fiend" obsessed with Welsh rabbit, or rarebit. McCay used the strip to explore psychological themes revealed through the human unconscious. He pursued the idea further in "Little Nemo in Slumberland" (1905), which featured the dream adventures of a young boy. McCay's comics were especially noted for their artistic craftsmanship. One of his few artistic rivals was American painter Lyonel Feininger, whose short-lived comic creations, "The Kin-der Kids" (1906) and "Wee Willie Winkie's World" (1906), are full of stunning imagery and whimsical humor. In 1907 Bud Fisher's comic strip "Mutt and Jeff" debuted. The strip was an immediate success, depicting the antics of Mutt, a scruffy idler, and his friend Jeff, who somehow believes that he is the prizefighter Jim Jeffries. "Mutt and Jeff" was the first successful comic strip to run every day, and it established the form as an important daily newspaper feature. B 1910s and 1920s Mickey Mouse Perhaps the world's most famous cartoon character, Mickey Mouse was created by American animator Walt Disney in the late 1920s. Mickey became a star in Steamboat Willie (1928), the first animated cartoon to feature sound. He went on to appear in countless cartoons, comics, and animated films such as Fantasia (1940). SYGMA/Corbis In the second and third decades of the 20th century, comics began to flower as an art form. Cartoonist George Herriman ushered in a new era in American comics with "Krazy Kat," which first appeared on newspaper pages as part of another strip in 1910 and became a separate strip in 1913. The strip revolved around three characters: Krazy Kat, Ignatz Mouse, and Offissa Pupp (a bulldog). Krazy loved Ignatz, but the mouse did not return the feelings and threw bricks at Krazy. Offissa Pupp, a police officer, was constantly putting Ignatz in jail. "Krazy Kat" was especially noted for its innovative artistic style and its use of shifting, abstract backgrounds. Many comic strips of this era reflected the social changes of the time. For example, in 1912, as the women's suffrage movement gained strength, Cliff Sterrett created "Polly and Her Pals," a comic strip about an independent woman. George McManus's work reflected immigrant and ethnic themes, such as in "Bringing Up Father" (1913), which chronicled the life of an Irish immigrant worker and his social-climbing wife. In 1914 Harry Hershfield created the strip "Abie the Agent," about a middleclass Jewish businessman. By appealing to adult readers, these features helped broaden the audience for comic strips. Another unique comic of the era that appealed mostly to adults was "The Inventions of Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts" (1914), created by Rube Goldberg. Goldberg's work featured wildly complex and ingenious contraptions rigged to fulfill what were often trivial purposes, such as turning on a light. The phrase "a Rube Goldberg device" has become a part of the American lexicon, referring to anything that is unnecessarily intricate or complex. The growth of the comic strip industry in the late 1910s was greatly helped by the syndication of comic strips. In journalism, syndication is the contracting for the publication of the same piece of work in multiple newspapers. The business practice was made possible by the formation of newspaper syndicates such as King Features, founded in 1914. While the major newspaper chains still hired and featured their own comic strip artists, syndication allowed small-town newspapers to run daily comic strips relatively inexpensively by purchasing them from the syndicates, who employed their own cartoonists. In the 1920s comic strips that focused on families were popular. The editor most responsible for the trend was Joseph Patterson of the New York News. Under his guidance Sidney Smith developed "The Gumps" (1917), about the ambitions of a lower-middle-class family. Another family-oriented News strip was "Gasoline Alley" (1918), created by Frank King, which mixed humor, domesticity, and small-town nostalgia as it described the doings of a group of friends and neighbors. One of the few comic strips to permit its characters to age, "Gasoline Alley" endured through changing times and continues to be published today. A variation on the family theme was provided by so-called daughter-of-the-house comic strips that focused on the lives of young women, including Martin Branner's "Winnie Winkle" (1920) and Russ Westover's "Tillie the Toiler" (1921). Also remaining popular were strips that featured groups of children as the main characters. These had been a staple of the comic strip from the early days, and new creations included Gene Byrnes's "Reg'lar Fellers" (1917), Ad Carter's "Just Kids" (1923), and Percy Crosby's "Skippy" (1925). Other strips included Billy De Beck's "Barney Google" (1919), which followed the misadventures of a born loser; Harold Gray's "Little Orphan Annie" (1924), about a girl who is adopted by a millionaire; E. C. Segar's "Thimble Theater" (1919); Frank Willard's "Moon Mullins" (1923); and Milt Gross's "Nize Baby" (1927). C 1930s to Mid-1940s In the 1930s adventure and action strips dominated the comic strip form. The first example of this type appeared as early as 1906, with "Hairbreadth Harry," the first strip that did not have a distinct ending each week. Instead, the strip introduced a suspense situation, which forced readers to wait until the next appearance of the strip to discover how events turned out. The cliffhanger, as the final panel of impending danger was called, became an essential element of adventure comic strips. The adventure trend truly began in 1929 when two major comic strips of this type were introduced. One was "Buck Rogers," a science-fiction strip about a military man and his adventures in the 25th century. The other was "Tarzan," which was based on the jungle tales of American writer Edgar Rice Burroughs and drawn exceptionally well by Harold Foster and, later, Burne Hogarth. In 1931 Chester Gould created the first detective strip, "Dick Tracy," which became a model for similar comics and featured hard-hitting stories on contemporary themes such as Prohibition. In 1934 Alex Raymond produced three strips of international renown: "Secret Agent X-9," "Jungle Jim," and "Flash Gordon." Of these, "Flash Gordon" is perhaps the most famous, following the adventures of a space traveler as he battles evildoers such as Ming the Merciless, emperor of the planet Mongo. Other action-adventure strips became hugely successful during this era. One long-lasting strip was Foster's "Prince Valiant" (1937), which incorporated themes of Arthurian legend and described the exploits of one of the knights of the Round Table. Other well-known strips of the time included Milton Caniff's "Terry and the Pirates" (1934) and Frank Godwin's "Connie," which began in 1927 as a conventional daughter-of-the-house strip but evolved into an adventure strip in the 1930s. Another adventure strip starring a woman, Dalia (Dale) Messick's "Brenda Starr" (1940), featured an intrepid reporter. Two other important action-adventure strips of this period were created by Lee Falk: "Mandrake the Magician" (1934) and "The Phantom" (1936). Despite the dominance of these action strips, popular humorous comics also appeared in the late 1920s and 1930s. Popeye the Sailor, famous for his reliance on spinach to make him strong, debuted in "Thimble Theater" in 1929. In 1930 Chic Young created "Blondie," which featured a typical American suburban family: Blondie, her husband Dagwood, and (eventually) their children Alexander and Cookie. Over time, the changes in "Blondie" have reflected social changes, especially among women, as Blondie has evolved from a flapper (a term used to describe fun-loving fashionable women in the 1920s and 1930s) to a housewife to an entrepreneur with her own business. Another successful humor strip was "Li'l Abner," which Al Capp debuted in 1934. The strip depicted small-town life and featured many memorable characters, including Li'l Abner himself, his wife Daisy Mae, his parents Mammy and Pappy Yokum, and the detective Fearless Fosdick. Another character from the strip was Sadie Hawkins, and from her fictional attempts to catch a husband comes the modern tradition of Sadie Hawkins Day, when girls take the initiative and ask boys out. The Walt Disney character Mickey Mouse was successfully adapted from the movie screen to the comics in 1930, and Donald Duck followed in 1936. Another gently humorous newspaper comic strip that proved popular was "Archie" (1947), which focused on a group of high school students and their daily lives. The "Archie" characters first appeared in another format--comic books--beginning in 1941. During World War II (1939-1945), many comic strip artists created heroes who served in the armed services, and war themes dominated the stories. The two most noteworthy strips were Roy Crane's "Buz Sawyer" (1943) and Frank Robbin's "Johnny Hazard" (1944). Another strip that came out shortly after the war, "Steve Canyon" (1947) by Milton Caniff, starred a United States Air Force colonel. D Late 1940s and 1950s Charles Schulz Cartoonist Charles Schulz began drawing his comic strip "Peanuts" in 1950 and continued it for nearly 50 years. The chronicles of Charlie Brown, his dog Snoopy (shown here), and their friends remain popular around the world. The characters have also been the focus of many animated television specials and even plays. Ben Margot/AP/Wide World Photos After World War II ended, the trend in comics moved toward strips that dealt thoughtfully with intellectual questions. The forerunner was Walt Kelly's "Pogo" (1948), a strip with animals as the main characters, but that nonetheless dealt with some of the major social, political, and moral questions of the times. Charles Schulz, whose "Peanuts" strip (1950) became one of the most beloved and successful comics ever, created such characters as Charlie Brown, his sister Sally, his dog Snoopy, the bird Woodstock, and friends Lucy, Linus, Schroeder, and Peppermint Patty. These characters--all of them children or animals--dealt with the trials of life using penetrating humor and insight, reflecting on issues such as self-worth, unrequited love, and the pursuit of happiness. "Peanuts" was turned into a series of popular animated television specials beginning in the 1960s. Other strips that broadened the editorial voice of the comics included Jules Feiffer's eponymous "Feiffer" (1956), a weekly strip featuring a nameless modern dancer who served as the artist's voice for social and political issues of the times; Mell Lazarus's "Miss Peach" (1957), set in a school; and Johnny Hart's "B.C." (1958), which explored human nature with cavemen and cavewomen who have modern sensibilities. Another notable development of this period was the soap-opera strip. Such comics concentrated on relationships and typically featured more conversation than action. One of the earliest such strips was "Mary Worth" (1940; begun as "Apple Mary" in 1934). Later followed soap-opera strips such as "Rex Morgan, M.D." (1948) and "On Stage" (1957). Traditional humor also remained popular, with creations such as Mort Walker's "Beetle Bailey" (1950), featuring a hapless private in the United States Army; "Hi and Lois" (1954), also created by Walker, about a traditional suburban family; and Hank Ketcham's "Dennis the Menace" (1951), about a young boy constantly finding his way into trouble. E 1960s and 1970s Garry Trudeau Cartoonist Garry Trudeau displays one of his "Doonesbury" comic strips. Trudeau began drawing the strip in 1970, and its treatment of President Richard Nixon, the Vietnam War, and other political topics quickly attracted both fans and critics. "Doonesbury" earned Trudeau the 1975 Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning. Mark Lennihan/AP/Wide World Photos In the 1960s and early 1970s, fewer comic strips of lasting popularity appeared, but there were some exceptions. "The Wizard of Id" (1964), by Johnny Hart and Brant Parker, had a medieval setting and featured an insecure king. "Wee Pals" (1965) by Morrie Turner, one of the first successful black cartoonists, was a pioneer in featuring a multicultural cast of characters--in this case, a group of schoolchildren. "Broom Hilda" (1970), by Russ Myers, used a humorous witch as its main character. The political turmoil of the 1960s and early 1970s proved fertile ground for a young cartoonist named Garry Trudeau. His strip "Doonesbury" (1970) focused on a group of college-aged friends but also provided commentary on real people and political events. Frequently controversial, "Doonesbury" became the first comic strip to win a Pulitzer Prize, capturing the 1975 award for editorial cartooning. Other important comics included "Quincy" (1970), by Ted Shearer, starring an interracial group of children; "Zippy the Pinhead" (1970), an unconventional strip featuring the skewed observations and catch phrases of a clown. "Hägar the Horrible" (1973), by Dik Browne, focused on the adventures--both military and domestic--of a rotund Viking. In the late 1970s, there was a strong resurgence of innovative humor strips. "Cathy" (1976), by Cathy Guisewite, chronicled the challenges that women face in the modern world. In 1977 the Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist Jeff McNelly created "Shoe," a newsroom satire in which the assorted characters are different types of birds. In 1978 Jim Davis's "Garfield," a strip about a demanding cat and his befuddled master, made its first appearance. "For Better or for Worse" (1978), by Canadian Lynn Johnston, focused on the comical aspects of everyday family life. Unlike most cartoonists, Johnston has allowed the characters of her strip to age and even die. F 1980s to the Present The decade of the 1980s saw several new comic strips that explored the edges of the form both editorially and artistically. Berkeley Breathed's "Bloom County" (1980) was an unconventional and satiric strip with a bizarre cast of characters, including Bill, a scrawny, addiction-prone cat; Opus, a lusty, self-obsessed penguin; Milo, a little boy who is a tabloid-style journalist; Oliver Wendell Jones, a young scientist and computer hacker; the neurotic Binky; and other assorted quirky animals and humans. Another very popular strip of the era was Bill Watterson's "Calvin and Hobbes" (1985), about a hyperactive six-year-old and his tiger sidekick, a stuffed animal who only comes alive for the boy. The little boy's frequent imaginary interactions with space aliens and dinosaurs allowed Watterson to produce extremely ambitious and creative strips, especially in the larger Sunday format. Other, more conventional strips that emerged during the decade included "Kudzu" (1981), "Sally Forth" (1982), and "Mother Goose and Grimm" (1984). As the modern workplace became more technological, few strips reflected this change. One that did, Scott Adams's "Dilbert" (1989), examined the trials and travails of corporate office workers and became a huge success. Another social trend that the comics slowly began to catch up with during this period was the rise in single-parent and nontraditional households. The strip "Stone Soup" (1995), by Jan Eliot, followed the lives of two sisters, one widowed and one divorced, who struggle to raise their children and maintain their sanity. The late 1980s and 1990s saw an influx of black artists to the comics page. The strips "Curtis" (1988), "Herb & Jamaal" (1989), and "Jump Start" (1990) all emerged within a short time span and feature black characters in a variety of situations. In 1996 Aaron McGruder debuted "The Boondocks," a sometimes-controversial comic strip about two black boys who have to adjust when they move from the city to live with their grandfather in the suburbs. Other new strips in the 1990s could be construed as designed to fill in audience slots pertaining to specific family situations. Examples of this included "Baby Blues" (1990), about new parents; "Zits" (1997), about a teenage boy and his bewildered parents; and "Nest Heads" (1998), about a couple dealing with their grown children moving out. Occupying its own niche is "Mutts" (1994), a strip about two dogs and a cat in the tradition of "Krazy Kat." IV COMIC BOOKS Comic books are booklets that come in varying sizes, and are most often in color. The length of comic books allows them to tell more involved stories than comic strips can. The design of the panels can also differ from comic strips, which nearly always consist of three or four equally sized square panels per strip. In comic books, the number of panels on each page can differ, as can their size and shape. Sometimes one scene can occupy an entire page. The forerunners of the comic book were 19th-century picture stories popular in Europe, such as Histoires en Estampes (1846-1847; Stories in Etchings) by Swiss artist Rodolphe Töppfer. In North America the earliest comic books were reprintings of comic strips in book form. This practice began as early as 1897 with The Yellow Kid. In the early 1900s the publisher of the comic strips "Buster Brown," "The Katzenjammer Kids," and "Happy Hooligan" issued color reprints of these strips. Other companies followed suit in ensuing decades, with the reprinting of such standards as "Bringing Up Father," "Mutt and Jeff," "Little Orphan Annie," and "The Gumps." A 1930s Batman The crime-fighting Batman was one of the earliest comic book heroes. Shown here is the 1939 cover of the first Batman comic, drawn by artist Bob Kane. The character is still popular in graphic novels, movies, and comic books today. Michael Barson/Archive Photos The first comic book to be published with some brand-new material was The Funnies, which ran for 13 issues in 1929. Some early comic books were created for manufacturers to give away as a special bonus, such as Funnies on Parade, which was made for Proctor & Gamble in 1933. The first comic book to sell on newsstands was Famous Funnies in 1934. In 1935 came the appearance of New Fun, the first comic book containing exclusively original material. New Fun was published by DC Comics, which would go on to become one of the largest comic book publishers in the world. In 1937 DC began publishing Detective Comics, the first series utilizing a single theme from issue to issue. Comic books vaulted into the public consciousness in 1938 with the debut of the character Superman in Action Comics. Superman, who came from a dying planet as a child, was endowed with special abilities under the Earth's sun--he could fly and boasted superhuman strength, X-ray vision, and other powers. He also had a secret identity as a mild-mannered newspaper reporter named Clark Kent. The popular new character sent sales of Action Comics soaring, and an American myth was born. The success of Superman ensured the viability of comic books as a form and gave rise to countless other superheroes. One of them was Batman, so named for his costume that looked like a bat. He fought evildoers not with superhuman powers but with uncommon physical skills and intelligence. This character debuted in 1939 in Detective Comics and quickly became as well known as Superman. Both characters have been featured in television series and motion pictures through the years, gaining further popularity. B 1940s and 1950s During World War II the demand for superheroes ran high, and several of the most famous and enduring characters debuted during this period. These heroes included Captain America, who battled Nazis beginning in 1941; Wonder Woman (1941), who boasted superhuman strength and speed, special bracelets that deflected bullets, and a magic lasso; and others, such as The Sub-Mariner (1939), Green Lantern (1940), the Flash (1940), and Captain Marvel (1940). After the boom of the war years and with the early coming of television, comic-book readership dropped dramatically. Many publishers went out of business, and others turned to stories featuring violence and horror. The most extreme case was William Gaines's line of horror comics that became popular during this period under the EC label, including titles such as Crypt of Terror, The Vault of Horror, and The Haunt of Fear. This trend toward violence and horror tales resulted in a public outcry that reached a peak in 1954. In that year psychiatrist Frederic Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent, a book sharply critical of the comic book industry, and the U.S. Senate held hearings on Juvenile Delinquency (Comic Books). To prevent government censorship, publishers were compelled to set up the Comics Code Authority (CCA), a self-regulating body with broad policing powers. The comic book code saved the industry from probable ruin, but it also stifled creativity in the field, discouraging artists and publishers from exploring new styles and genres. Sales slipped even more. C 1960s and 1970s In the 1960s the comic book industry began to move in new directions. A leader in this trend was Marvel Comics, which introduced a host of new superheroes who had special powers but also suffered many of the same insecurities as real people. The first such heroes were the Fantastic Four, created by Marvel's Stan Lee in 1961: Mr. Fantastic, who could stretch his elastic body almost without limit; the Invisible Woman, who had the power to make herself and other things invisible; the Human Torch, who could transform his body into flame; and the Thing, who was made of orange rock and had superhuman strength. Despite their powers, the Fantastic Four suffered the same difficulties in life as anyone else. The Fantastic Four comic would also introduce other popular superheroes-with-flaws, such as the Silver Surfer (1966). The Incredible Hulk (1962) was another character that Lee created. The Hulk was the "alter ego" of Dr. Bruce Banner, a scientist who was accidentally exposed to massive amounts of gamma radiation. After the exposure, whenever Banner's temper flared he turned into a green-skinned, muscle-bound monster called the Hulk. The most successful Marvel character may have been Spider-Man, another Lee character who debuted in 1962. Spider-Man's true identity was Peter Parker, an awkward teenager who is bitten by a radioactive spider and gains speed, agility, and strength. Despite these advantages, Parker still suffers many of the same personal problems as a regular high school boy--and this helped make him one of the comics' most popular characters. Marvel's innovations led to huge sales and a spot at the top of the industry along with DC. A different sort of innovation took place during this period among so-called underground cartoonists such as Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, and S. Clay Wilson. These artists covered a wide range of subject matter--even incorporating sexual content and drug use--as they pushed the limits of comics, or comix, as they liked to call them. Eventually these underground artists achieved popular recognition and some became famous, like Crumb, the creator of memorable characters such as Fritz the Cat and Mr. Natural. The offbeat comic magazine Mad was first published in the 1950s, but it gained in popularity during the industry changes of the 1960s. The publication was one of the sole survivors of the EC Comics empire, which crumbled under governmental scrutiny of the industry in the early 1950s. Featuring a host of talented regular writers and artists, Mad's anti-authoritarian skewering of popular culture--everything from movie satires to comic strips and side-panel cartoons--found a wide audience among teenagers and young adults of the era. The 1970s were troubled years for the comic book industry. A sharp drop in the birthrate meant that fewer children were buying comics, and sales declined. While some publishers tried to promote new comic magazines aimed at an older audience, others drastically cut their production. Television also continued to compete for the same audience, offering animated cartoons (The Superfriends, 1973-1986) and even live-action shows (The Incredible Hulk, 1977-1982; Wonder Woman, 1976-1979) based on comic book characters. With newsstand sales plummeting and many companies folding, the comic book medium was saved at the end of the decade by direct market distribution. This method consisted of a network of specialized comic stores that bought comic books on a nonreturnable basis--once the stores purchased the comic books from the publishers, the stores could not return unsold comics. Bolstered by guaranteed sales of their product, comic book publishers rebounded. Marvel preserved its position as a leading comic book publisher with a successful line of X-Men comics in the 1970s. The X-Men were mutants who had special powers, such as being able to levitate objects or shoot a powerful beam from their eyes. The original X-Men appeared in 1963, but the comic did not gain a large following until the late 1970s. The series eventually spawned an entire line of spinoffs, such as X-Factor and X-Terminator. D 1980s to the Present Art Spiegelman Underground cartoonist Art Spiegelman earned critical and commercial acclaim for his two-volume graphic novel, Maus: A Survivor's Tale (1986 and 1991). The work, based on the experiences of Spiegelman's parents during the Holocaust of World War II, received a special Pulitzer Prize citation in 1992. Jacques M. Chenet/Corbis While Marvel continued to create new, multifaceted characters, DC Comics maintained a steady course based on their traditional titles. DC's business was strongly helped in the late 1970s and 1980s by the box-office success of a series of movies featuring the Superman and Batman characters. This allowed the company to experiment with new titles, such as The New Teen Titans, Camelot 3000, Starman, and Watchmen. The direct market also allowed a host of small comic book publishers, the so-called independents, to survive and sometimes flourish. Many of the most intriguing creations of this period came from the independents, including Howard Chaykin's American Flagg!, Harvey Pekar's American Splendor, and Jeff Smith's Bone. Tremendously popular as well during this time was the wacky comic Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, which came out in 1984 and featured four genetically altered turtles who were trained in martial arts and named after Renaissance artists: Leonardo, Michelangelo, Donatello, and Raphael. The Turtles became a youth craze during the decade, spawning huge toy and merchandising sales and a series of Hollywood movies. A major change during this period was an industry shift from producing comics for children to creating titles and story lines aimed at older teens and adults. A sign of this change was the emergence and growing popularity of the graphic novel, an extended story told in comic book style but with as much focus on the text as the artwork. The graphic novel that had a major role in this trend was Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986), written and drawn by Frank Miller. This Batman was no cartoon superhero, but rather a vengeful, brooding crime fighter who appealed mostly to older readers. Many graphic novels use the form to make powerful statements on significant themes. A chief example is Maus: A Survivor's Tale, written and drawn by underground cartoonist Art Spiegelman. The work personalizes the Holocaust, telling the story of Spiegelman's parents, who survived imprisonment in Nazi concentration camps during World War II. The comic book form, which includes the use of mice for Jewish characters and cats for the Nazis, serves to make the gripping story even more stark and powerful. Years in the making, Maus was published in two volumes (1986 and 1991) to critical and commercial acclaim, receiving a special Pulitzer Prize citation in 1992. Other comic artists who became known for their graphic novels were Will Eisner, whose autobiographical graphic novels include A Contract with God (1985), The Dreamer (1986), and Dropsie Avenue (1995); and Howard Cruse, who published Stuck Rubber Baby (1995), a coming-of-age tale set in the American South in the 1960s. Several works of this genre dealt with the war in the former Yugoslavia: Joe Kubert's Fax from Sarajevo (1996) and Joe Sacco's Safe Area Gorazde (2000). The 1990s were turbulent years for the comic book business, however, as the industry experienced both boom and bust. After an influx of new collectors and speculators boosted sales in the early 1990s, the market collapsed in 1994 and comic book stores closed in large numbers. The downturn hammered industry leader Marvel, which filed for bankruptcy in 1996, but the company rebounded as the industry's fortunes improved at the end of the century. Some of the most popular and innovative comic book artists of the early 21st century were those who produced more complex, subtle works, such as Daniel Clowes (Ghost World, 1998; David Boring, 2000) and Chris Ware (Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, 2000). Far from being targeted solely at hardcore comics fans, these works have received mainstream recognition, as when Clowes's Ghost World was made into a 2001 movie starring actors Steve Buscemi and Thora Birch. Another 2001 movie derived from a graphic novel was the thriller From Hell, with actors Johnny Depp and Heather Graham. V CURRENT TRENDS The state of the comic at the beginning of the 21st century is mixed. Comic strips have established themselves as a vital part of the daily newspaper, followed by millions of readers who are quick to complain if one of their favorites is dropped. At the same time, many of the top cartoonists--such as Berkeley Breathed and Bill Watterson--have left the profession, whether because they are creatively burnt out, financially secure through book and merchandise sales, or frustrated by the limits of the medium (or a combination of these). There may never be another cartoonist with the longevity and commitment of Charles Schulz, who died in February 2000 on the night before his final "Peanuts" strip ran. Schulz alone authored the groundbreaking strip for 50 years, and he also decided that the strip would not continue after his death (except in reruns). Comic books may face even greater challenges in the future. The form has undergone great change, from an industry focused on children to one catering to older readers. Many major retail chains have dropped or reduced their shelf space for comic books, leaving primarily urban specialty stores as the main distribution channel. At the same time, competition from the Internet, video games, motion pictures, and proliferating television shows has cut heavily into sales. Although there are still successful titles being produced by talented artists and writers, the comic book industry will have to battle hard to regain this lost market share in the future. Contributed By: Maurice Horn Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.