To have a conscience involves being conscious of the moral quality

Publié le 22/02/2012

Extrait du document

«

ends up doing the right thing.

Talk of a ‘perverted' conscience may mean that a person's ultimate convictions are

judged to be perverse, as in the first strand identified; or that their capacity to know good from evil, in general or in

the particular case, has been distorted or corrupted.

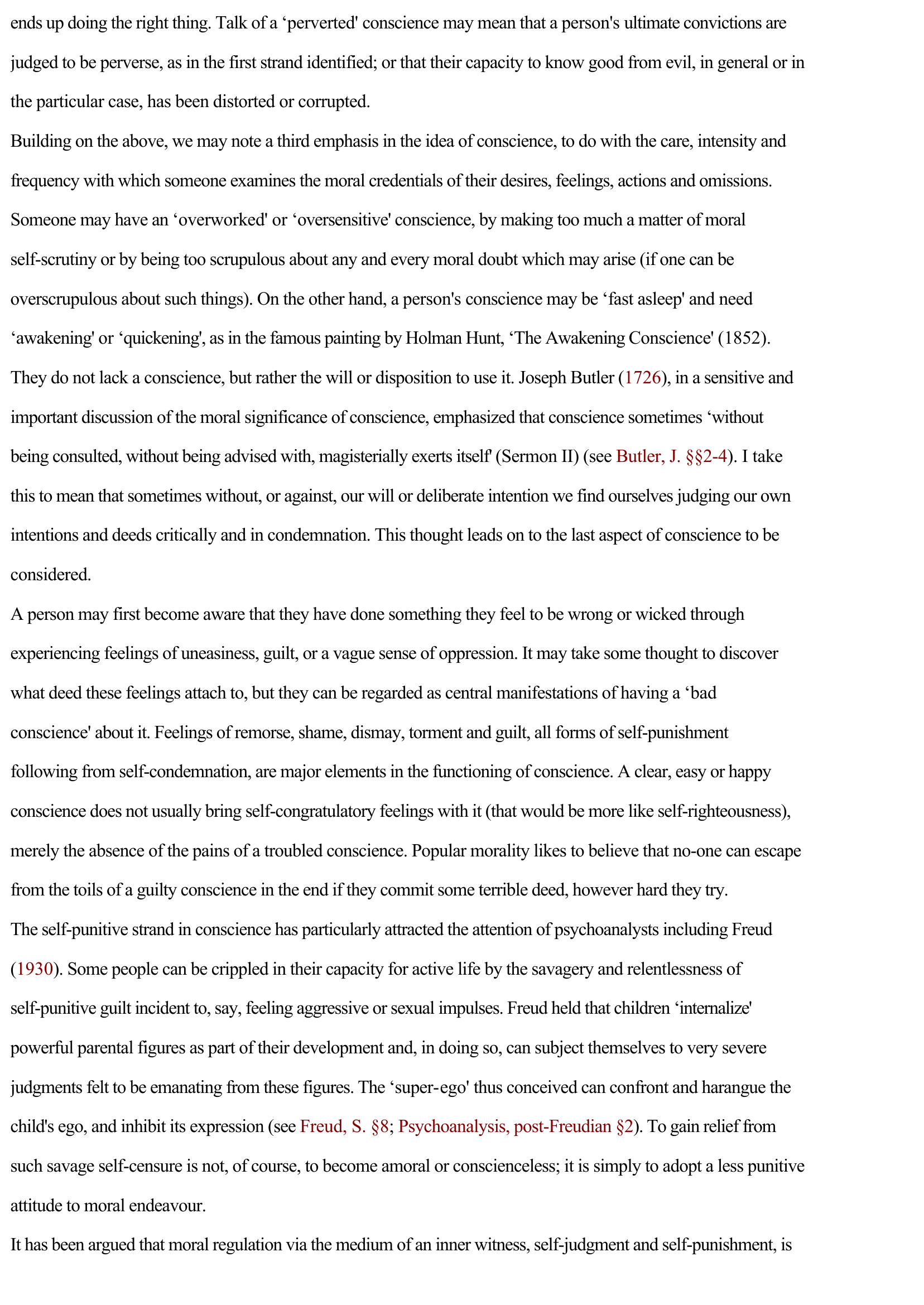

Building on the above, we may note a third emphasis in the idea of conscience, to do with the care, intensity and

frequency with which someone examines the moral credentials of their desires, feelings, actions and omissions.

Someone may have an ‘overworked' or ‘oversensitive' conscience, by making too much a matter of moral

self-scrutiny or by being too scrupulous about any and every moral doubt which may arise (if one can be

overscrupulous about such things).

On the other hand, a person's conscience may be ‘fast asleep' and need

‘awakening' or ‘quickening' , as in the famous painting by Holman Hunt, ‘The Awakening Conscience' (1852).

They do not lack a conscience, but rather the will or disposition to use it.

Joseph Butler ( 1726 ), in a sensitive and

important discussion of the moral significance of conscience, emphasized that conscience sometimes ‘without

being consulted, without being advised with, magisterially exerts itself' (Sermon II) (see Butler, J.

§§2-4 ).

I take

this to mean that sometimes without, or against, our will or deliberate intention we find ourselves judging our own

intentions and deeds critically and in condemnation.

This thought leads on to the last aspect of conscience to be

considered.

A person may first become aware that they have done something they feel to be wrong or wicked through

experiencing feelings of uneasiness, guilt, or a vague sense of oppression.

It may take some thought to discover

what deed these feelings attach to, but they can be regarded as central manifestations of having a ‘bad

conscience' about it.

Feelings of remorse, shame, dismay, torment and guilt, all forms of self-punishment

following from self-condemnation, are major elements in the functioning of conscience.

A clear, easy or happy

conscience does not usually bring self-congratulatory feelings with it (that would be more like self-righteousness),

merely the absence of the pains of a troubled conscience.

Popular morality likes to believe that no-one can escape

from the toils of a guilty conscience in the end if they commit some terrible deed, however hard they try.

The self-punitive strand in conscience has particularly attracted the attention of psychoanalysts including Freud

(1930 ).

Some people can be crippled in their capacity for active life by the savagery and relentlessness of

self-punitive guilt incident to, say, feeling aggressive or sexual impulses.

Freud held that children ‘internalize'

powerful parental figures as part of their development and, in doing so, can subject themselves to very severe

judgments felt to be emanating from these figures.

The ‘super -ego' thus conceived can confront and harangue the

child's ego, and inhibit its expression (see Freud, S.

§8 ; Psychoanalysis, post-Freudian §2 ).

To gain relief from

such savage self-censure is not, of course, to become amoral or conscienceless; it is simply to adopt a less punitive

attitude to moral endeavour.

It has been argued that moral regulation via the medium of an inner witness, self-judgment and self-punishment, is.

»

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- Commentaire Texte Bergson L'évolution créatrice, l'élan vital et la conscience

- expose sur la conscience

- La conscience de soi suppose-t-elle autrui ?

- LA CONSCIENCE (résumé)

- La conscience me fait-elle connaître que je suis libre ?