Daniel Defoe: Robinson Crusoe (Sprache & Litteratur).

Publié le 13/06/2013

Extrait du document

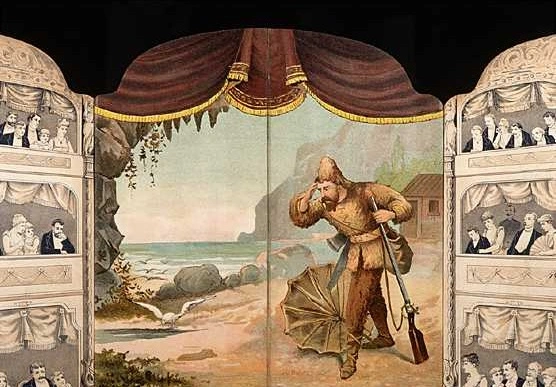

Daniel Defoe: Robinson Crusoe (Sprache & Litteratur). Daniel Defoe verband in seinem 1719 veröffentlichten Roman The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (Das Leben und die seltsamen Abenteuer des Robinson Crusoe) erstmals Fakten - in seinem Fall einen Augenzeugenbericht - mit Fiktion. Seine Geschichte rund um den Schiffbrüchigen Robinson Crusoe revolutionierte das Genre des Abenteuer- und Jugendromans. Im ersten der beiden folgenden Auszüge schildert der Protagonist die Erkundung des Schiffswracks und seine erfreuliche Entdeckung, einen großen Teil der Lebensmittel und nützlichen Gegenstände an Bord unversehrt vorzufinden. Im zweiten Auszug beschreibt er das Äußere seines eingeborenen Gefährten, den er nach dem Wochentag ihres Zusammentreffens Freitag nennt. Daniel Defoe: Robinson Crusoe When I waked it was broad day, the weather clear, and the storm abated, so that the sea did not rage and swell as before; but that which surprised me most was, that the ship was lifted off in the night from the sand where she lay, by the swelling of the tide, and was driven up almost as far as the rock which I first mentioned, where I had been so bruised by the dashing me against it; this being within about a mile from the shore where I was, and the ship seeming to stand upright still, I wished myself on board, that, at least, I might save some necessary things for my use. When I came down from my apartment in the tree, I looked about me again, and the first thing I found was the boat, which lay as the wind and the sea had tossed her up upon the land, about two miles on my right hand. I walked as far as I could upon the shore to have got to her, but found a neck or inlet of water, between me and the boat, which was about half a mile broad; so I came back for the present, being more intent upon getting at the ship, where I hoped to find something for my present subsistence. A little after noon, I found the sea very calm, und the tide ebbed so far out, that I could come within a quarter of a mile of the ship; and here I found a fresh renewing of my grief: for I saw evidently, that if we had kept on board, we had been all safe - that is to say, we had all got safe on shore, and I had not been so miserable as to be left entirely destitute of all comfort and company, as I now was. This forced tears from my eyes again; but as there was little relief in that, I resolved, if possible, to get to the ship - so I pulled off my clothes, for the weather was hot to extremity, and took the water. But when I came to the ship, my difficulty was still greater to know how to get on board; for, as she lay aground and high out of the water, there was nothing within my reach to lay hold of. I swam round her twice, and the second time I spied a small piece of rope, which I wondered I did not see at first, hang down by the fore-chains, so low as that with great difficulty I got hold of it, and, by the help of that rope, got up into the forecastle of the ship. Here I found that the ship was bulged, and had a great deal of water in her hold, but that she lay so on the side of a bank of hard sand, or rather earth, and her stern lay lifted up upon the bank, und her head low almost to the water: by this means all her quarter was free, and all that was in that part was dry; for you may be sure my first work was to search and to see what was spoiled, and what was free, and first I found that all the ship's provisions were dry and untouched by the water: and being very well disposed to eat, I went to the bread-room and filled my pockets with biscuit, and ate it as I went about other things, for I had no time to lose. I also found some rum in the great cabin, of which I took a large dram, and which I had indeed need enough of to spirit me for what was before me. Now I wanted nothing but a boat, to furnish myself with many things which I foresaw would be very necessary to me. (...) He was a comely handsome fellow, perfectly well made, with straight long limbs, not too large, tall, and well shaped, and, as I reckon, about twenty-six years of age. He had a very good countenance, not a fierce and surly aspect, but seemed to have something very manly in his face, and yet he had all the sweetness and softness of an European in his countenance too, especially when he smiled: his hair was long and black, not curled like wool; his forehead very high and large, and a great vivacity and sparkling sharpness in his eyes. The colour of his skin was not quite black, but very tawny, and yet not of an ugly yellow nauseous tawny, as the Brazilians and Virginians, and other natives of America are, but of a bright kind of a dun olive colour, that had in it something very agreeable, though not very easy to describe. His face was round and plump, his nose small, not flat like the negroes, a very good mouth, thin lips, and his teeth fine, well set, and white as ivory. After he had slumbered, rather than slept, above half an hour, he waked again, and comes out of the cave to me, for I had been milking my goats, which I had in the enclosure just by: when he espied me, he came running to me, laying himself down again upon the ground, with all the possible signs of an humble thankful disposition, making many antic gestures to show it. At last he lays his head flat upon the ground, close to my foot, and sets my other foot upon his head, as he had done before: and, after this, made all the signs to me of subjection, servitude, and submission imaginable, to let me know how much he would serve me as long as he lived. I understood him in many things, and let him know I was very well pleased with him. In a little time I began to speak to him, and teach him to speak to me; and first, I made him know his name should be Friday, which was the day I saved his life, and I called him so for the memory of the time: I likewise taught him to say Master, and then let him know that was to be my name: I likewise taught him to say Yes and No, and to know the meaning of them. I gave him some milk in an earthen pot, and let him see me drink it before him, and sop my bread in it; and I gave him a cake of bread to do the like, which he quickly complied with, and made signs that it was very good for him. Daniel Defoe: The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. London o. J., S. 44f., S. 184f. Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Liens utiles

- Daniel Defoe (Sprache & Litteratur).

- Robinson Crusoe (extrait) Daniel Defoe (...) In a little time I began to speak to him, and teach him to speak to me; and, first, I made him know his name should be Friday, which was the day I saved his life.

- Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart: Die Fürstengruft (Sprache & Litteratur).

- Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart (Sprache & Litteratur).

- Daniel Casper von Lohenstein (Sprache & Litteratur).