Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Charles Darwin

Publié le 09/01/2010

Extrait du document

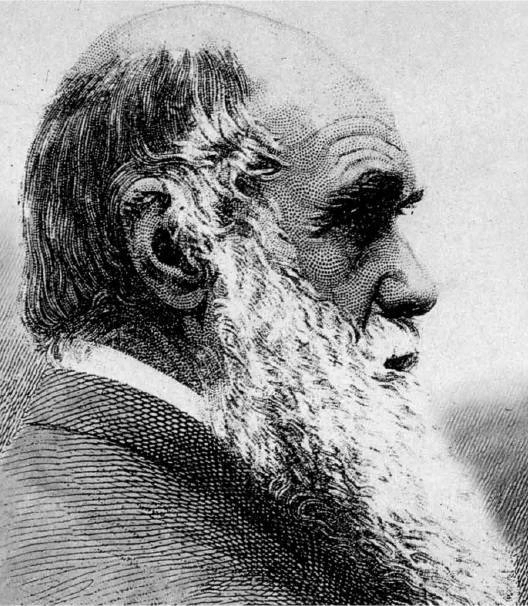

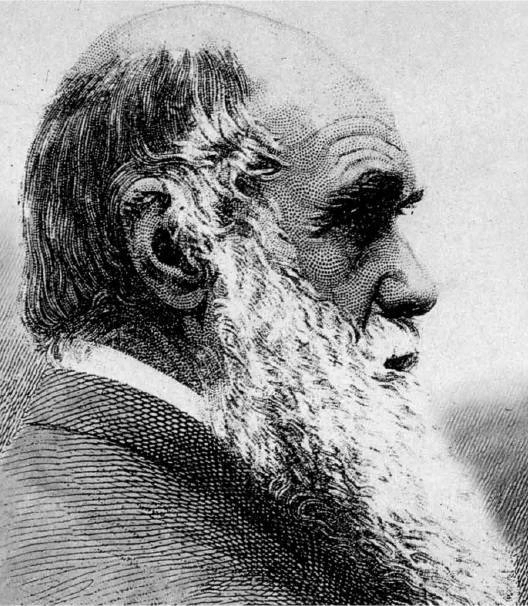

In his funeral oration on Karl Marx, Engels described the materialist conception of history as a scientific breakthrough comparable with Darwin’s discovery of evolution by natural selection. Unlike Marx’s theory, Darwin’s discovery was a genuine scientific advance, and the detailed discussion of it belongs to the history of science. But it casts a backward light on several philosophical issues we have encountered earlier, and philosophical as well as scientific conclusions have been drawn from it. Hence even an outline history of philosophy would be incomplete without a brief account of the theory and its philosophical implications. Charles Darwin was born in Shrewsbury in 1809 and attended the school there before university studies in Edinburgh and Christ’s College, Cambridge. After taking his degree in 1831 he joined HMS Beagle on a five-year tour of the globe as resident naturalist; he published a record of his botanical and geological researches on the cruise in a series of works between 1839 and 1846. During the 1840s he began to develop the theory of natural selection which he eventually published in his great work The Origin of Species in 1859. This was followed by The Descent of Man in 1871 and a series of treatises on variations of structure and behaviour within and across species, which continued almost up to his death in 1882.

«

cousins, descended from a common ancestor.The case for Darwin's theory was enormously strengthened in the twentieth century with the discovery of themechanisms of heredity and the development of molecular genetics.

It would not be to my purpose, and would bebeyond my competence, to evaluate the scientific evidence for Darwinism.

But it is necessary to spend some timeon the philosophical implications of his theory, assuming that it is well established.From Darwin's time until the present, evolutionary theory has met opposition from many Christians.

At the meetingof the British Association in 1860 the evolutionist T.

H.

Huxley reported that the Bishop of Oxford inquired from himwhether he claimed descent from an ape on his father's or his mother's side.

Huxley – according to his own account– replied that he would rather have an ape for a grandfather than a man who misused his gifts to obstruct scienceby rhetoric.Darwin's theory obviously clashes with a literal acceptance of the Bible account of the creation of the world inseven days.

Moreover, the length of time which would be necessary for evolution to take place would be immenselylonger than the six thousand years which Christian fundamentalists believed to be the age of the universe.

But anon-literal interpretation of Genesis had been adopted by theologians as orthodox as St Augustine, and fewChristians in the twentieth century find great difficulty in accepting that the earth may have existed for billions ofyears.

It is more difficult to reconcile an acceptance of Darwinism with belief in original sin.

If the struggle forexistence had been going on for aeons before humans evolved, it is impossible to accept that it was man's firstdisobedi¬ence and the fruit of the forbidden tree which brought death into the world.

But that is a problem for thetheologian, not the philosopher, to solve.On the other hand, it is wrong to suggest, as is often done, that Darwin disproved the existence of God.

For allDarwin showed, the whole machinery of natural selection may have been part of a Creator's design for the universe.After all, belief that we humans are God's creatures has never been regarded as incom¬patible with our being thechildren of our parents; it is equally compatible with our being, on both sides, descended from the ancestors of theapes.

Some theistsmaintain that we inherit only our bodies, and not our souls, from our parents.

They can no doubt extend their thesisto Adam's inheritance from his non-human progenitor.At most, Darwin disposed of one argument for the existence of God: namely, the argument that the adaptation oforganisms to their environment shows the existence of a benevolent creator.

But Darwin's theory still leaves muchto be explained.

The origin of individual species from earlier species may be explained by the mechanisms ofevolutionary pressure and selection.

But these mechanisms cannot be used to explain the origin of species as such.For one of the starting points of explanation by natural selection is the existence of true-breeding populations,namely species.

Modern Darwinians, of course, do offer us explana¬tions of the origin of speciation, and of lifeitself; but these explanations, whatever their merits, are not explanations by natural selection.In the case of the human species, there is a particular difficulty in explaining by natural selection the origin oflanguage.

It is easy enough to understand how natural selection can favour a certain length of leg, because thereis no difficulty in describing a single individual as long-legged, and we can see how length of legs may beadvantageous to an individual.

It does not seem plausible to suggest that in a parallel way the use of languagemight be favoured by natural selection, because it is not possible to describe an individual as a language user at astage before there was a community of language-users.

For language is a rule-governed, communal activity, totallydifferent from the signalling systems to be found in non-humans.

Because of the social and conventional nature oflanguage there is something very odd about the idea that language may have evolved because of the advantagespossessed by language-users over non-language-users.

It seems almost as absurd as the suggestion that banksevolved because those born with an innate cheque-writing ability had an advantage in the struggle for life overthose born without it.The most general philosophical issue raised by Darwinism concerns the nature of causality.

The fourth of Aristotle'sfour causes was the goal or end of a structure or activity.

Explanations falling in this category were calledteleological after the Greek word for end, telos.

Teleological explanations of activity, in Aristotle, have two features.First, they explain an activity by reference not to its starting point, but to its terminus.

Secondly, they do theirexplaining by exhibiting arrival at the terminus as being in some way good for the agent whose activity is to beexplained.

Thus, Aristotle will explain downward motion of heavy bodies as a movement towards their natural place,the place where it is best for them to be.

Similarly, teleological explanations of structures in an organism will explainthe development of the structure in the individual organism by reference to its completed state, and exhibit thebenefit conferred on the organism by the structure once completed: thus, ducks grow webbed feet so that theycan swim.

Descartes was contemptuous of Aristotelian teleology; he maintained that the explanation of every movement andevery physical activity must be mechanistic, that is to say it must be given in terms of initial conditions describedwithout evaluation.

Descartes offered no good argument for his contention; but in the subsequent history ofscience, blows were dealt at each of the two elements of Aristotelian teleology, by Newton and Darwin separately.Newtonian gravity, no less than Aristotelian natural motion, provides an explanation by reference to a terminus;gravity is a centripetal force, a force ‘by which bodies are drawn, or impelled, or in any way tend, towards a pointas to a centre'.

Where Newton's explanation differs from Aristotle's is that it involves no suggestion that it is in anyway good for a body to arrive at the centre to which it tends.

Darwinian explanations, like Aristotle's, demand thatthe terminus of the process to be explained shall be beneficial to the relevant organism; but unlike Aristotle, Darwinexplains the process not by the pull of the final state but by the initial conditions in which the process began.

Thered teeth and red claws involved in the struggle for existence were, of course, in pursuit of a good, namely thesurvival of the individual organism to which they belonged; but they were not in pursuit of the good which finallyemerged from the process, namely the survival of the fittest species.Not that Darwin's discovery put an end to the search for final causes.

Far from it: contemporary biologists are much.

»

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- De l'origine des espèces de Charles Darwin (résumé et analyse)

- ORIGINE DES ESPÈCES PAR VOIE DE SÉLECTION NATURELLE (De l’) de Charles Darwin - résumé, analyse

- Charles Robert Darwin (Vie, œuvre, Apports, Concepts, Commentaires).

- Charles Robert Darwin

- Charles Darwin 1809-1882 Né à Shrewsbury, mort à Down (Kent).