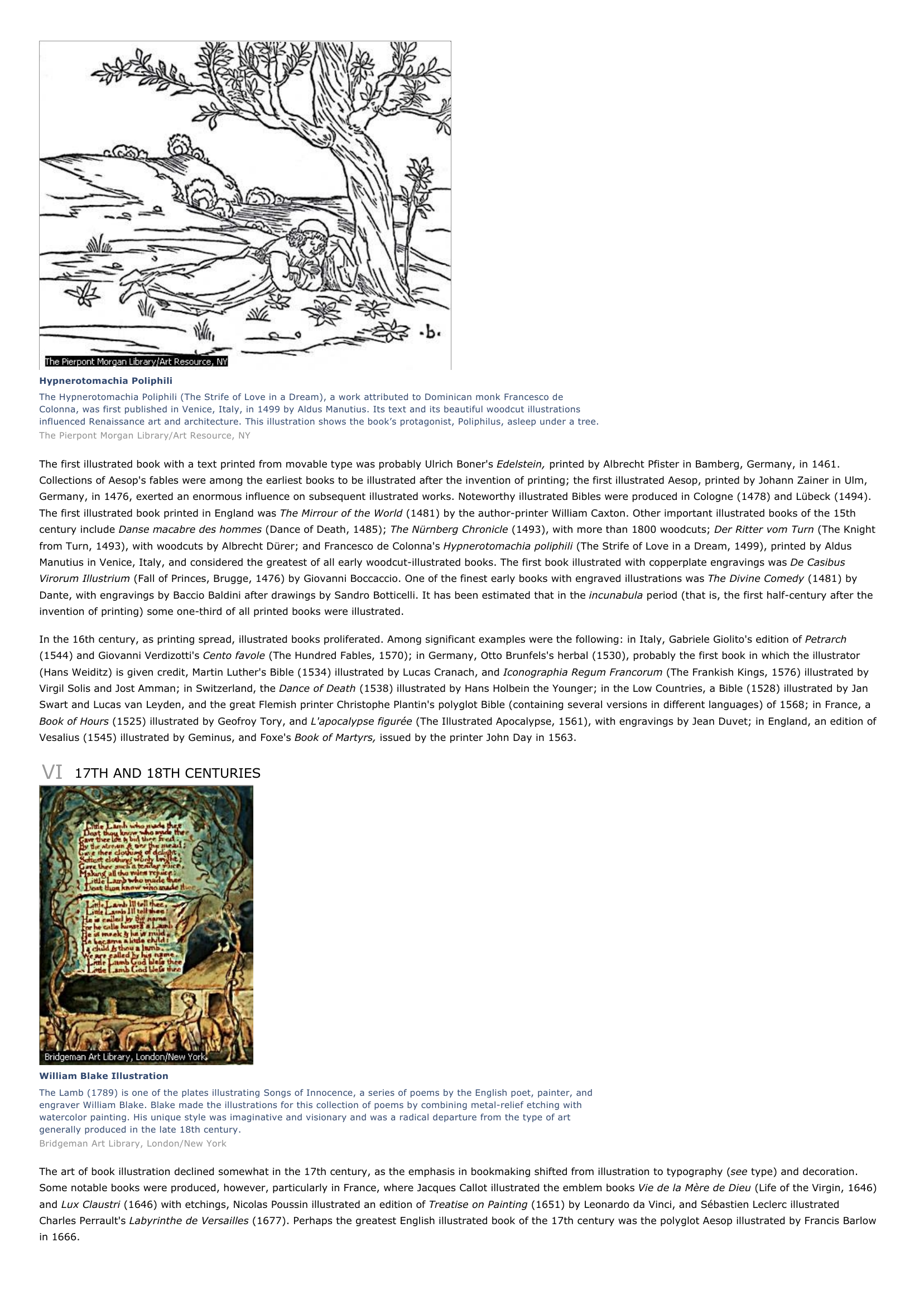

Illustration I INTRODUCTION Illustration, pictorial material appearing with a text and amplifying or enhancing it. Although illustrations may be maps, charts, diagrams, or decorative elements, they are more usually representations of scenes, people, or objects related in some manner--directly, indirectly, or symbolically--to the text they accompany. The historical origins of illustration are as ancient as those of writing. The pictographs of early humans, and the hieroglyphics of such early civilizations as the Egyptian, contain the roots of both illustration and text. II HAND ILLUSTRATION Section of the Egyptian Book of the Dead The Egyptian Book of the Dead was a text containing prayers, spells, and hymns, the knowledge of which was to be used by the dead to guide and protect the soul on the hazardous journey through the afterlife. Beginning in the 18th Dynasty, the Book of the Dead was inscribed on papyrus. This section of one such book, from the early 19th Dynasty, shows the final judgment of the deceased (in this case Hu-Nefer, the royal scribe) before Osiris, god of the dead. Hieroglyphs as well as illustrations portray the ritual of weighing the deceased's heart to determine whether he can be awarded eternal life. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Before the invention of printing, books (that is, manuscripts in scroll or codex form) were illustrated by hand. The earliest surviving example of an illustrated book is an Egyptian papyrus scroll from about 2000 BC. In ancient Egypt the Book of the Dead, a text designed to be placed in tombs, was the most frequently illustrated work. In classical Europe the earliest illustrations seem to have been made for scientific texts. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle referred to illustrations, now lost, accompanying his biological writings. Illustrations in the form of authors' portraits were the next development, followed by the illustration of literary texts such as the Iliad and the Odyssey. Literary illustration was also being produced in China beginning about the 5th century BC. Artists in medieval Europe illustrated texts with paintings in the form of miniatures, pictorially embellished initial letters, or marginal decorations. In the Islamic world, Persian and Mughal artists illustrated works of poetry and history with delicate, jewel-like paintings. Duplicate illustrations, like duplicate manuscripts, could be produced only through copying by hand. Medieval books were most often made of parchment, which had replaced papyrus about III AD300; but by the late Middle Ages paper had come into use. See Illuminated Manuscripts. PRINTED REPRODUCTION METHODS The first mechanical reproduction of illustrations was achieved by means of wooden blocks. A picture was drawn on the smooth surface of a block, the wood on either side of the lines of the drawing was carved away, and the resulting relief image was smeared with pigment or ink and printed on parchment or paper. The process could be repeated again and again, producing many identical pictures from a single block. Sometimes an entire book page, text as well as illustration, was cut on a block; books made by this technique are called block books. With their necessarily limited texts, most block books were simple, crude productions aimed at the nearly unlettered general public, for whom they presented religious messages; the Biblia Pauperum (Paupers' Bible) and Ars moriendi (Art of Dying) are famous examples. See Prints and Printmaking. The printing press, on which an extensive text could be printed from movable type, also made it possible for separate woodcut illustrations to be printed along with the text (see Printing). The need for greater detail in illustrations led to the development of techniques for engraving and etching metal plates, usually copper. The mezzotint, a refined form of copperplate engraving capable of reproducing subtle gradations of light and shadow, was developed in the 18th century, as was the aquatint, by which the effect of watercolor painting could be simulated. Late in the century white-line wood engraving was perfected; in this technique, metal-engraving tools were used on the end-grain surface of very hard wood to produce pictures of considerable delicacy, often with images appearing in white against a dark background. At the end of the 18th century lithography was invented, providing the artist with greater fluidity and scope in illustration technique; the possibilities were increased by the introduction, in the first half of the 19th century, of color lithography. Photography, perfected in the second half of the 19th century, ultimately provided versatile photomechanical methods of reproducing the illustrator's original, in whatever medium it might be created. IV USES OF PRINTED ILLUSTRATIONS Beginning in the late 18th century, the illustrated book was joined by the illustrated periodical, which flourished thereafter. Fiction had been illustrated almost from its beginnings, and by the 19th century the practice had grown so that few novels were issued without at least a frontispiece (an illustration facing or preceding the title page in a book), often in color. The illustration of topographical, architectural, and botanical works also proliferated in the 19th century. In the 20th century, the practice of illustrating adult fiction declined. Illustration of books for adults came to be confined principally to nonfiction, with emphasis on illustrations as learning tools, especially in textbooks and other reference books. The illustration of children's literature, however, began to be increasingly common in the 19th century, and after the middle of the 20th century it accounted for the greater part of all book illustration. Periodicals came to rely heavily on photographic illustration. V 15TH AND 16TH CENTURIES Hypnerotomachia Poliphili The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (The Strife of Love in a Dream), a work attributed to Dominican monk Francesco de Colonna, was first published in Venice, Italy, in 1499 by Aldus Manutius. Its text and its beautiful woodcut illustrations influenced Renaissance art and architecture. This illustration shows the book's protagonist, Poliphilus, asleep under a tree. The Pierpont Morgan Library/Art Resource, NY The first illustrated book with a text printed from movable type was probably Ulrich Boner's Edelstein, printed by Albrecht Pfister in Bamberg, Germany, in 1461. Collections of Aesop's fables were among the earliest books to be illustrated after the invention of printing; the first illustrated Aesop, printed by Johann Zainer in Ulm, Germany, in 1476, exerted an enormous influence on subsequent illustrated works. Noteworthy illustrated Bibles were produced in Cologne (1478) and Lübeck (1494). The first illustrated book printed in England was The Mirrour of the World (1481) by the author-printer William Caxton. Other important illustrated books of the 15th century include Danse macabre des hommes (Dance of Death, 1485); The Nürnberg Chronicle (1493), with more than 1800 woodcuts; Der Ritter vom Turn (The Knight from Turn, 1493), with woodcuts by Albrecht Dürer; and Francesco de Colonna's Hypnerotomachia poliphili (The Strife of Love in a Dream, 1499), printed by Aldus Manutius in Venice, Italy, and considered the greatest of all early woodcut-illustrated books. The first book illustrated with copperplate engravings was De Casibus Virorum Illustrium (Fall of Princes, Brugge, 1476) by Giovanni Boccaccio. One of the finest early books with engraved illustrations was The Divine Comedy (1481) by Dante, with engravings by Baccio Baldini after drawings by Sandro Botticelli. It has been estimated that in the incunabula period (that is, the first half-century after the invention of printing) some one-third of all printed books were illustrated. In the 16th century, as printing spread, illustrated books proliferated. Among significant examples were the following: in Italy, Gabriele Giolito's edition of Petrarch (1544) and Giovanni Verdizotti's Cento favole (The Hundred Fables, 1570); in Germany, Otto Brunfels's herbal (1530), probably the first book in which the illustrator (Hans Weiditz) is given credit, Martin Luther's Bible (1534) illustrated by Lucas Cranach, and Iconographia Regum Francorum (The Frankish Kings, 1576) illustrated by Virgil Solis and Jost Amman; in Switzerland, the Dance of Death (1538) illustrated by Hans Holbein the Younger; in the Low Countries, a Bible (1528) illustrated by Jan Swart and Lucas van Leyden, and the great Flemish printer Christophe Plantin's polyglot Bible (containing several versions in different languages) of 1568; in France, a Book of Hours (1525) illustrated by Geofroy Tory, and L'apocalypse figurée (The Illustrated Apocalypse, 1561), with engravings by Jean Duvet; in England, an edition of Vesalius (1545) illustrated by Geminus, and Foxe's Book of Martyrs, issued by the printer John Day in 1563. VI 17TH AND 18TH CENTURIES William Blake Illustration The Lamb (1789) is one of the plates illustrating Songs of Innocence, a series of poems by the English poet, painter, and engraver William Blake. Blake made the illustrations for this collection of poems by combining metal-relief etching with watercolor painting. His unique style was imaginative and visionary and was a radical departure from the type of art generally produced in the late 18th century. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The art of book illustration declined somewhat in the 17th century, as the emphasis in bookmaking shifted from illustration to typography (see type) and decoration. Some notable books were produced, however, particularly in France, where Jacques Callot illustrated the emblem books Vie de la Mère de Dieu (Life of the Virgin, 1646) and Lux Claustri (1646) with etchings, Nicolas Poussin illustrated an edition of Treatise on Painting (1651) by Leonardo da Vinci, and Sébastien Leclerc illustrated Charles Perrault's Labyrinthe de Versailles (1677). Perhaps the greatest English illustrated book of the 17th century was the polyglot Aesop illustrated by Francis Barlow in 1666. In the 18th century France led the world in book illustration, with such efforts as the Fables (1755) of Jean de La Fontaine illustrated by Jean Baptiste Oudry, the same author's Contes (Tales, 1762) illustrated by Pierre Choffard and Charles Eisen, and an edition of the Contes (1795) illustrated by Jean Honoré Fragonard. Important English illustrated books in this period included an Aesop (1722) with engravings by Samuel Croxall, Hudibras (1726) by Samuel Butler, with engravings by William Hogarth; Poems (1753) by Thomas Gray, illustrated by Richard Bentley; and Anatomy of the Horse (1766) illustrated by George Stubbs. The German artist Daniel Chodowiecki illustrated The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759-1767) by Laurence Sterne. In the latter part of the 18th century the most significant English book illustration was done by Thomas Bewick, who revived and perfected white-line wood engraving in such books as History of Quadrupeds (1790), and by the poet-artist William Blake, whose "illuminated books," beginning with Songs of Innocence (1789), returned to an approach similar to that used in the block books of the 15th century. Japanese artists illustrated books with colored woodcuts of birds, flowers, and everyday life, as for example Shigemasa (Mirror of Fair Women,1776), Masanobu Kitao (Yoshiwara,1784), and Utamaro (Bird Book,1791). VII 19TH AND 20TH CENTURIES Isolde Isolde is an illustration by the late-19th-century English painter and graphic artist Aubrey Beardsley. The use of decorative line, stylized figure, and flat space exemplifies the art nouveau style. Beardsley did a large number of illustrations for magazines and books. His use of dramatic darks and lights is well suited to the graphic medium. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York In the 19th century, illustration again flourished, most markedly in England in the 1860s. Early in the century the London publisher Rudolph Ackermann produced a great many works on English topography and architecture, with hand-colored aquatints by such prominent illustrators as Thomas Rowlandson (The Microcosm of London,1808). The great landscape painter J. M. W. Turner illustrated a few books, such as Italy (1830); George Cruikshank, "Phiz" (Hablot K. Browne), and John Leech all produced famous illustrations for the novels of Charles Dickens. In the 1860s the Dalziel family of wood engravers produced celebrated books illustrated by such artists of the period as Charles Keene, John Everett Millais, and Birket Foster. Strong decorative elements marked the work of illustrators such as Aubrey Beardsley, who illustrated Salome (1894) by Oscar Wilde, and Edward Burne-Jones, who illustrated the Kelmscott Press Chaucer (1896). The productions of the influential craftsman William Morris at the Kelmscott Press emulated the medieval book, whereas the work of William Nicholson (London Types,1898) anticipated the 20th-century children's picture book. Artists who produced important book illustration in France during the 19th century included Eugène Delacroix, Honoré Daumier, Gustave Doré, Grandville (Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard), Gavarni (Sulpice Guillaume Chevalier), Édouard Manet, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. In Japan the tradition of colored woodcuts of everyday life was continued by such masters as Hokusai and Hiroshige (see Ukiyo-e). The most significant illustrated books of the early 20th century were produced in France. The Paris art dealer and publisher Ambroise Vollard commissioned illustrations by such renowned artists as Pierre Bonnard, Marc Chagall, André Derain, Raoul Dufy, Marie Laurencin, Aristide Maillol, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Rouault, and Maurice de Vlaminck. The era may be said to represent a final flowering of book illustration for adults, although some noteworthy contributions came from the later part of the century. The American artist Ben Shahn turned to book illustration toward the end of his career (for example, A Partridge in a Pear Tree,1959); and the American printmaker Fritz Eichenberg worked on editions of the works of such writers as Emily Brontë, William Shakespeare, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. VIII CHILDREN'S BOOKS Illustration from Alice In Wonderland English artist Sir John Tenniel illustrated the original Alice in Wonderland, a classic children's book written by English author Lewis Carroll in 1865. This illustration shows Alice at a tea party hosted by the Mad Hatter and the March Hare; the fourth guest is the Dormouse. Tenniel also illustrated Carroll's Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There (1872). In addition to Tenniel's book illustrations he was a prolific magazine illustrator and was known for his caricatures of famous political figures. Van Bucher/Photo Researchers, Inc. Illustrated children's books, which would ultimately account for the major portion of all illustrated books, grew steadily in numbers during the 19th century, especially in England and the United States. Important illustrators included William Mulready (The Butterfly's Ball,1807); George Cruikshank ( Grimm's Fairy Tales,1823); Edward Lear (A Book of Nonsense,1846); F. O. C. Darley (Rip Van Winkle,1850); Gustave Doré (Les contes de Perrault,1862); John Tenniel (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland,1865); Richard Doyle (In Fairyland,1870); Arthur Hughes (Sing-Song,1872); Winslow Homer (Courtin',1874); Randolph Caldecott (The House that Jack Built,1878); Kate Greenaway (A Apple Pie,1886); Walter Crane (The Baby's Own Aesop,1887); and Beatrix Potter (The Tale of Peter Rabbit,1900). These artists exerted a strong influence on the course of later illustration in children's books. Also noteworthy were the American illustrator Howard Pyle (The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood,1883); the French artist Louis Maurice Boutet de Monvel (Jeanne d'Arc,1896); and the English watercolorist Arthur Rackham (Aesop's Fables,1912). In the 20th century, noteworthy illustration for children's books was produced in England by Leslie Brooke (Johnny Crow's Garden,1903); Edmund Dulac (Arabian Nights Entertainments,1907); E. H. Shepard (Winnie-the-Pooh,1926); Brian Wildsmith (Brian Wildsmith's Mother Goose,1964); Edward Ardizzone ( Tim and Ginger,1965); and Kit Williams (Masquerade,1979). Important American illustrators of children's books include N. C. Wyeth (Treasure Island,1924); Maxfield Parrish ( Mother Goose in Prose,1897); Wanda Gág (Millions of Cats,1928); Robert Lawson (The Story of Ferdinand,1936); Ludwig Bemelmans (Madeline,1939); Ezra Jack Keats (The Snowy Day,1962); and Maurice Sendak (Where the Wild Things Are,1963). Modern classics in the field have also come from Spain (Rafael Munoa's Platero y yo,1963); France (Jean de Brunhoff's Babar books, beginning in 1931); Germany (Reiner Zimnik's Jonas the Fisherman,1956, and Marlene Reidel's Eric's Journey,1960); and Japan (Yashima Taro's Crow Boy,1955). Most of the contemporary illustrated books are those produced for children. See Children's Literature. Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.