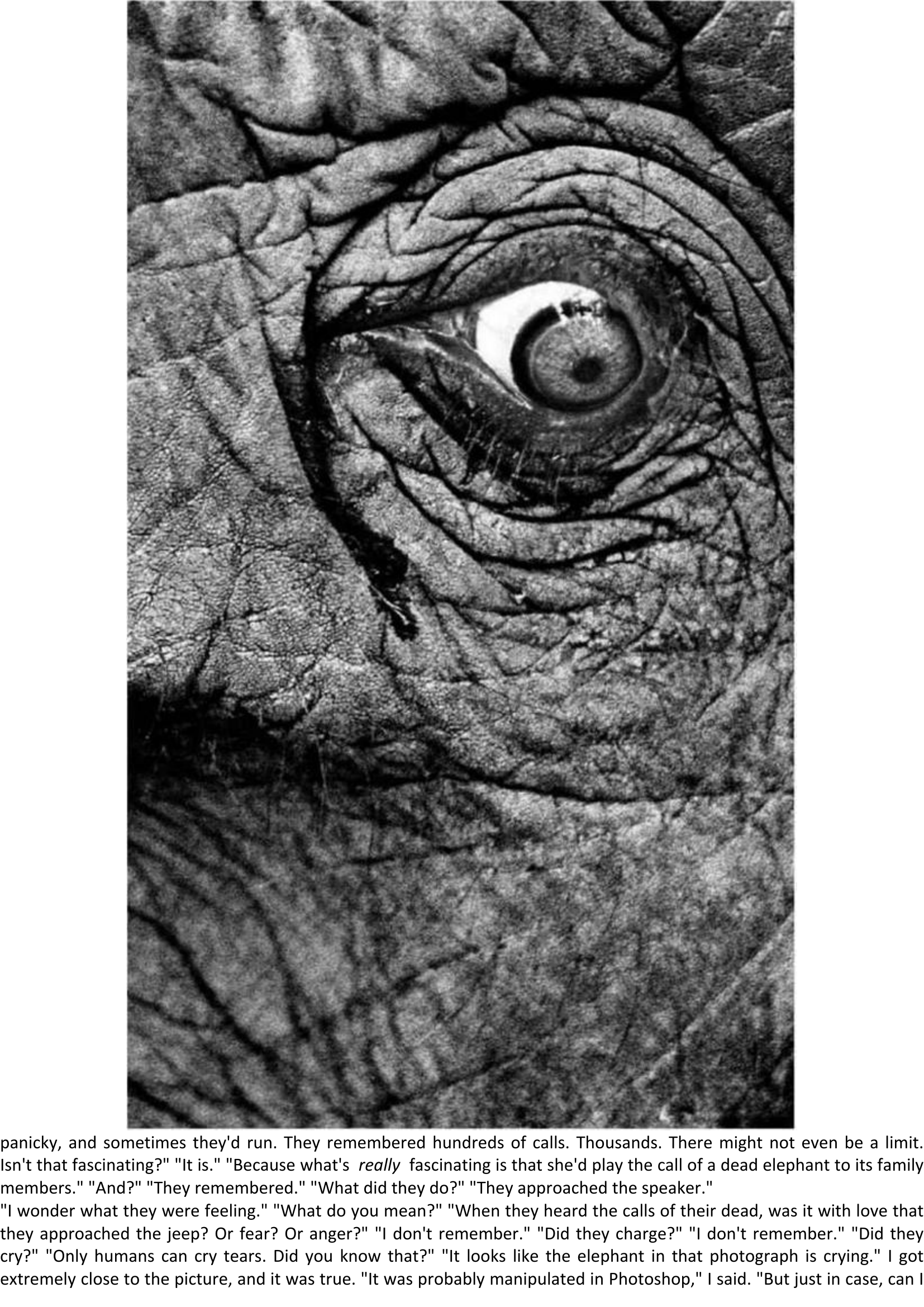

man in the other room called again, this time extremely loudly, like he was desperate, but she didn't pay any attention, ike she didn't hear it, or didn't care. touched a lot of things in her kitchen, because it made me feel OK for some reason. I ran my finger along the top of her icrowave, and it turned gray. "C'est sale," I said, showing it to her and cracking up. She became extremely serious. "That's embarrassing," she said. "You should see my laboratory," I said. "I wonder how that could have happened," she aid. I said, "Things get dirty." "But I like to keep things clean. A woman comes by every week to clean. I've told her a million times to clean everywhere. I've even pointed that out to her." I asked her why she was getting so upset about such a small thing. She said, "It doesn't feel small to me," and I thought about moving a single grain of sand one millimeter. I took a wet wipe from my field kit and cleaned the microwave. Since you're an epidemiologist," I said, "did you know that seventy percent of household dust is actually composed of uman epidermal matter?" "No," she said, "I didn't." "I'm an amateur epidemiologist." "There aren't many of those." Yeah. And I conducted a pretty fascinating experiment once where I told Feliz to save all the dust from our apartment for year in a garbage bag for me. Then I weighed it. It weighed 112 pounds. Then I figured out that seventy percent of 112 ounds is 78.4 pounds. I weigh 76 pounds, 78 pounds when I'm sopping wet. That doesn't actually prove anything, but it's eird. Where can I put this?" "Here," she said, taking the wet wipe from me. I asked her, "Why are you sad?" "Excuse me?" "You're sad. Why?" The coffee machine gurgled. She opened a cabinet and took out a mug. "Do you take sugar?" I told her yes, because Dad lways took sugar. As soon as she sat down, she got back up and took a bowl of grapes from her refrigerator. She also took out cookies and put them on a plate. "Do you like strawberries?" she asked. "Yes," I told her, "but I'm not hungry." She put out some strawberries. I thought it was weird that there weren't any menus or little magnetic calendars or ictures of kids on her refrigerator. The only thing in the whole kitchen was a photograph of an elephant on the wall next o the phone. "I love that," I told her, and not just because I wanted her to like me. "You love what?" she asked. I pointed t the picture. "Thank you," she said. "I like it, too." "I said I loved it." "Yes. I love it." "How much do you know about elephants?" "Not too much." "Not too much a little? Or not too much nothing?" "Hardly anything." "For example, did you know that scientists used to think that elephants had esp?" "Do you mean E.S.P.?" "Anyway, elephants can set up meetings from very faraway locations, and they know where their friends and enemies are going to be, and they can find water without any geological clues. No one could figure out how they do all of those things. So what's actually going on?" "I don't know." "How do they do it?" "It?" "How do they set up meetings if they don't have E.S.P.?" "You're asking me?" "Yes." "I don't know." "Do you want to know?" "Sure." "A lot?" "Sure." "They're making very, very, very, very deep calls, way deeper than what humans can hear. They're talking to each other. Isn't that so awesome?" "It is." I ate a strawberry. "There's this woman who's spent the last couple of years in the Congo or wherever. She's been making recordings of the calls and putting together an enormous library of them. This past year she started playing them back." "Playing them back?" "To the elephants." "Why?" I loved that she asked why. "As you probably know, elephants have much, much stronger memories than other mammals." "Yes. I think I knew that." "So this woman wanted to see just how good their memories actually are. She'd play the call of an enemy that was recorded a bunch of years earlier--a call they'd heard only once--and they'd get panicky, and sometimes they'd run. They remembered hundreds of calls. Thousands. There might not even be a limit. Isn't that fascinating?" "It is." "Because what's really fascinating is that she'd play the call of a dead elephant to its family members." "And?" "They remembered." "What did they do?" "They approached the speaker." "I wonder what they were feeling." "What do you mean?" "When they heard the calls of their dead, was it with love that they approached the jeep? Or fear? Or anger?" "I don't remember." "Did they charge?" "I don't remember." "Did they cry?" "Only humans can cry tears. Did you know that?" "It looks like the elephant in that photograph is crying." I got extremely close to the picture, and it was true. "It was probably manipulated in Photoshop," I said. "But just in case, can I take a picture of your picture?" She nodded and said, "Didn't I read somewhere that elephants are the only other animals that bury their dead?" "No," I told her as I focused Grandpa's camera, "you didn't. They just gather the bones. Only humans bury their dead." "Elephants couldn't believe in ghosts." That made me crack up a little. "Well, most scientists ouldn't say so." "What would you say?" "I'm just an amateur scientist." "And what would you say?" I took the picture. I'd say they were confused." hen she started to cry tears. thought, I'm the one who's supposed to be crying. "Don't cry," I told her. "Why not?" she asked. "Because," I told her. "Because what?" she asked. Since I didn't know why she was crying, I couldn't think of a reason. Was she crying about the elephants? Or something else I'd said? Or the desperate person in the other room? Or something that I didn't know about? I told her, "I bruise easily." She said, "I'm sorry." I told her, "I wrote a letter to that scientist who's making those elephant recordings. I asked if I could be her assistant. I told her I could make sure there were always blank tapes ready for recording, and I could boil all the water so it was safe to drink, or even just carry her equipment. Her assistant wrote back to tell me she already had an assistant, obviously, but maybe there would be a project in the future that we could work on together." "That's great. Something to look forward to." "Yeah." Someone came to the door of the kitchen who I guessed was the man that had been calling from the other room. He just stuck his head in extremely quickly, said something I didn't understand, and walked away. Abby pretended to ignore it, but I didn't. "Who was that?" "My husband." "Does he need something?" "I don't care." "But he's your husband, and I think he needs something." She cried more tears. I went over to her and I put my hand on her shoulder, like Dad used to do with me. I asked her what she was feeling, because that's what he would ask. "You must think this is very unusual," she said. "I think a lot of things are very unusual," I said. She asked, "How old are you?" I told her twelve--lie #59--because I wanted to be old enough for her to love me. "What's a twelve-year-old doing knocking on the doors of strangers?" "I'm trying to find a lock. How old are you?" "Forty-eight." "Jose. You look much younger than that." She cracked up through her crying and said, "Thanks." "What's a forty-eight-year-old doing inviting strangers into her kitchen?" "I don't know." "I'm being annoying," I said. "You're not being annoying," she said, but it's extremely hard to believe someone when they tell you that. I asked, "Are you sure you didn't know Thomas Schell?" She said, "I didn't know Thomas Schell," but for some reason I still didn't believe her. "Maybe you know someone else with the first name Thomas? Or someone else with the last name chell?" "No." I kept thinking there was something she wasn't telling me. I showed her the little envelope again. "But this is your last name, right?" She looked at the writing, and I could see that she recognized something about it. Or I thought I could see it. But then she said, "I'm sorry. I don't think I can help you." "And what about the key?" "What key?" I realized I hadn't even shown it to her yet. All of that talking--about dust, about elephants--and I hadn't gotten to the whole reason I was there. I pulled the key out from under my shirt and put it in her hand. Because the string was still around my neck, when she eaned in to look at the key, her face came incredibly close to my face. We were frozen there for a long time. It was like time was stopped. I thought about the falling body. "I'm sorry," she said. "Why are you sorry?" "I'm sorry I don't know anything about the key." Disappointment #3. "I'm sorry, too." Our faces were so incredibly close.