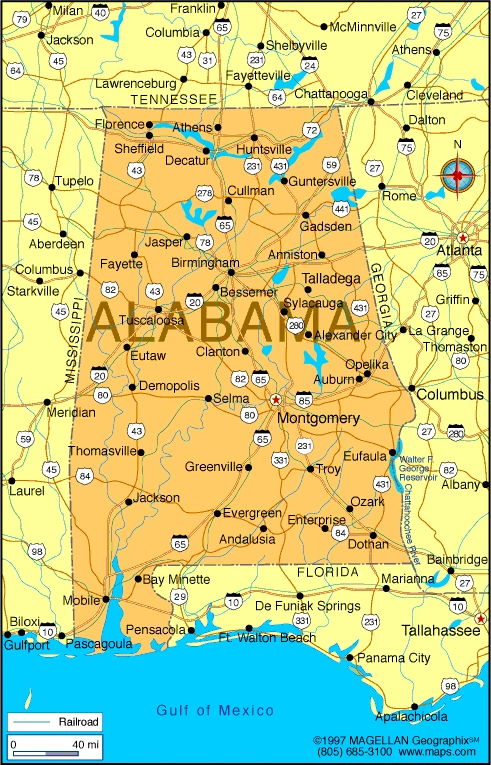

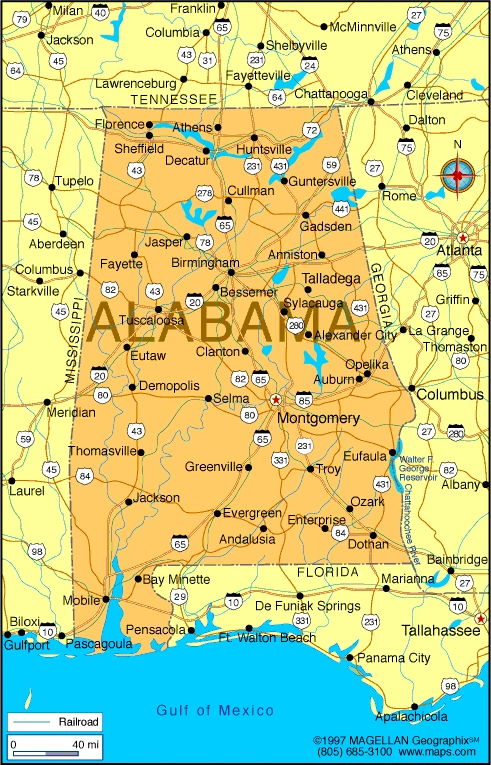

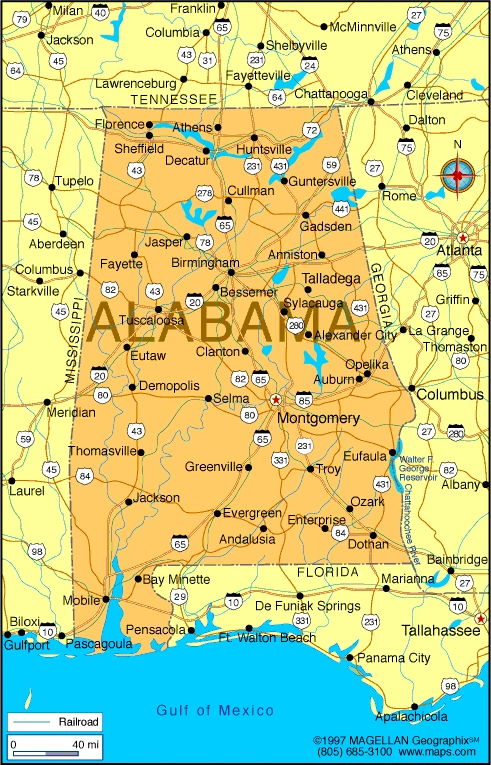

Alabama (state) - geography. I INTRODUCTION Alabama (state), in the east south central United States, at the southern end of the Appalachian Mountains and on the Gulf of Mexico. It is one of the principal states of the South and is often referred to as the Heart of Dixie. In the course of about 450 years, Spanish, French, British, and Confederate flags, as well as the Stars and Stripes, have flown over Alabama, and residents of the state have a deep-seated sense of history. Alabama entered the Union on December 14, 1819, as the 22nd state. The state capital, Montgomery, became the provisional capital of the Confederate States of America in 1861 and is popularly known as the Cradle of the Confederacy. A few Alabamian towns and cities still maintain an air of informal dignity and charm characteristic of the Old South, supported by prosperous cotton plantations. This popular image, however, was never wholly true of Alabama and is far less so now. Although cotton is still an important crop, corn, peanuts, soybeans, and other crops, with pasture grasses and woodlands, have taken over much of the former cotton lands. Modern agricultural machinery has replaced mules and picking cotton by hand. The most marked change in Alabama, however, has been its comparatively rapid industrialization, particularly in the second half of the 20th century. In the northwest the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) program of hydroelectric power production, begun in the 1930s, fostered the growth of giant fertilizer, munitions, and aluminum industries. Similar industrial expansion has occurred in central and southwestern areas, including around Birmingham, the state's largest city. Alabama received its name from the Alabama River, which in turn was named after a Native American tribe that inhabited the region at the time the first Europeans arrived. The name is believed to be a combination of two Choctaw words roughly meaning vegetation (alba) and gatherer (amo), which were applied to the Alabama, or Alibamon, people. While the state proudly displays its "Heart of Dixie" nickname on vehicle license plates, Alabama is also known as the Yellowhammer State. This nickname dates from the American Civil War (1861-1865), when a company of Alabama soldiers decked their uniforms with yellow trimmings that resembled the wing patches of the yellowhammer. II PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY Alabama covers 135,765 sq km (52,419 sq mi), including 2,476 sq km (956 sq mi) of inland water and 1,344 sq km (519 sq mi) of coastal water over which the state has jurisdiction. It is the 30th largest state in the Union. Roughly rectangular in shape, Alabama has a maximum distance north to south of 533 km (331 mi) and a maximum distance east to west of 338 km (210 mi). The mean elevation is about 150 m (500 ft). A Natural Regions From plateaus and uplands in the northeastern section of the state, the land slopes gradually southward across forested ridges, rolling prairie, and fertile valleys to the delta of the Mobile River on an arm of the Gulf of Mexico. Alabama can be divided into five natural regions: the Appalachian Plateaus, the Ridge and Valley province, the Piedmont, the Interior Low Plateau, and the Gulf Coastal Plain. The Appalachian Plateaus, the Ridge and Valley province, and the Piedmont together make up part of the vast Appalachian Region, or Appalachian Highland. The Appalachian Region, in Alabama, extends across much of the northern half of the state in a northeast-southwest direction. The northwestern part of the region is the Cumberland Plateau, which is one of the Appalachian Plateaus. It is an almost level sandstone upland that averages about 400 m (about 1,300 ft) above sea level and is drained by the Tennessee and Black Warrior rivers. The Ridge and Valley province is made up of sandstone ridges paralleled by fertile limestone valleys. The ridges impose a distinctive northeast-southwest trend on the local pattern of rivers, railroads, and highways. The meandering Coosa River is the main stream of the Ridge and Valley province. Southeast of the Coosa lie the rugged Talladega Mountains, which rise to 733 m (2,405 ft) above sea level at Cheaha Mountain, Alabama's highest point. Between the Talladega Mountains and the Georgia state line on the east is the Piedmont Plateau, a large area with numerous low hills and ridges. The Interior Low Plateau extends southward into northern Alabama from Tennessee. It is a limestone region that is made up of low uplands and broad valleys. The region is drained by the Tennessee River. The Gulf of Mexico portion of the Coastal Plain covers the remainder of the state. Sedimentary rocks, much younger than those of the Appalachian Region, underlie the Gulf Coastal Plain. The plain is by no means flat. Parallel bands of low, generally forested hills and ridges stretch across the plain from east to west. The ridges usually have a steep northern slope and a more gentle southern slope. They are separated by broad level lowlands, including the well-known Black Belt, which is a gently rolling prairie, 40 to 80 km (25 to 50 mi) wide, that extends across the state into Mississippi. The Black Belt, named for its fertile dark-colored soils, is one of the major agricultural regions of Alabama. In the extreme southwest, near the Gulf of Mexico, the plain becomes very flat and swampy. The southeastern part of the plain is a flat area, dotted with pine forests. Extensive areas of these forests have been cleared to provide excellent farming lands. B Rivers and Lakes Most of Alabama drains southward to the Gulf of Mexico. The principal rivers in the western half of the state are the Tombigbee and its chief tributary, the Black Warrior. Much of eastern and central Alabama is drained by the Alabama River and its headstreams, the Coosa and the Tallapoosa. The Tombigbee and Alabama unite north of Mobile to form the Mobile River, which flows into the Gulf of Mexico through Mobile Bay. The Mobile is roughly paralleled by the Tensaw River, which extends from the Mobile just below the junction of the Alabama and Tombigbee to the bay. The marshy floodplain between the two rivers is intersected by many meandering channels. Southeastern Alabama is drained by three major rivers, which all flow into the gulf. They are the Chattahoochee, which forms the southern part of the Alabama-Georgia state line, the Choctawhatchee, and the Conecuh. In the north the Tennessee River flows westward in a great bend across almost the entire width of the state before turning northward to join the Ohio River in Kentucky. The Tennessee is the most important river in northern Alabama and forms a section of a vast inland waterway system. There are no large natural lakes in Alabama. However, the state has several large reservoirs, including Wheeler Lake on the Tennessee River and R. L. Harris Reservoir on the Tallapoosa River. Also on the Tennessee and also part of the TVA system are Wilson Lake and Guntersville and Pickwick lakes, which lie partly in other states. Guntersville Lake is the largest in the state. Martin Lake is on the Tallapoosa River, and Weiss Reservoir (partly in Georgia) and Logan Martin, Lay, Mitchell, and Jordan lakes are on the Coosa River. Holt and Warrior reservoirs and Lakes Lewis Smith and Bankhead are on the Black Warrior River or its tributaries, and Miller's Ferry Reservoir is on the Alabama River. Lakes Harding and Eufaula and West Point Lake lie on the Chattahoochee River, on the Alabama-Georgia state line. C Coastline Alabama's coastline on the gulf is short, measuring 85 km (53 mi) from the Mississippi state line to the Perdido River on the Florida state line. When all of the indentations along the coast are measured, the state's shoreline is 977 km (607 mi) long. It includes the shores of Mobile Bay, an inlet 56 km (35 mi) long at the mouth of the Mobile River. Barrier beaches partly block the entrance to the bay, leaving narrow openings on either side of Dauphin Island. Dauphin and other islands along Alabama's coast west of Mobile Bay are separated from the mainland by Mississippi Sound. D Climate Alabama has a humid subtropical climate, with short, relatively mild winters and long warm summers. Temperature differences between the coastal and inland areas, however, are small. January averages range from about 11°C (57°F) at Mobile to about 7°C (44°F) at Birmingham. July averages are in the upper 20°s C (low 80°s F) at Mobile and at Birmingham. Very low or very high temperatures are unusual. The growing season, the period between the last killing frost of spring and the first killing frost of fall, ranges from about 200 days in the north to more than 300 days in the southwest. During the summer, daytime temperatures are frequently in the upper 20°s C (mid-80°s F) or higher and afternoon thundershowers are common. In winter, mild humid air masses from the gulf alternate with cold air masses from the north. Snow occasionally falls in the north. Rainfall is plentiful, ranging annually from about 1,350 mm (about 53 in) in the north to more than 1,730 mm (68 in) in the southwest. Most rainfall occurs in winter and early spring, but a second wet season occurs in July, owing primarily to thunderstorms. Tropical cyclones and, in some years, severe hurricanes are a threat to the coastal areas in summer. Winds, floods, and high tides accompanying the storms can cause considerable damage to crops and property. E Soils Alabama has a wide variety of soils. The most fertile are the limestone-derived loams and clays of the Tennessee Valley and of the Black Belt. Good farming soils are also found in the major river valleys and along the northern edge of the Gulf Coastal Plain. The sandy loams of the Cumberland Plateau and the southern Gulf Coastal Plain are easy to work, and good crops can be produced with the aid of fertilizers and crop rotation. In many parts of the state, however, the soils are now quite infertile, mainly because of poor farming practices over a long period of years. F Plant Life Plants grow luxuriantly throughout Alabama, because of the abundant rainfall, mild climate, and long frost-free season. Forests and woodlands cover 71 percent of the state. Hardwood species, such as chinkapin oak, tupelo, and bald cypress, which is frequently festooned with Spanish moss, are characteristic of the bottomlands of the southern river valleys. Chestnut oak, black oak, southern red oak, and species of hickory dominate the limestone valleys and uplands of the north, and species of oak and pine are frequently found in association in the northern sections of the Gulf Coastal Plain and the Appalachian Region. Most of the Gulf Coastal Plain and the Piedmont, however, lie in the vast southern pine region, where southern longleaf, shortleaf, loblolly, and slash pine are the principal species. The longleaf pine is the state tree of Alabama. Many flowering trees, such as the magnolia, and ornamental shrubs, such as the snow wreath, are native to Alabama. Mountain laurel, huckleberries, blackberries, sumac, and mistletoe grow wild in much of the state. Cane, one of the many native grasses, forms dense thickets in the south. Goldenrod, evening primrose, hairy vetch, White Cherokee rose, black-eyed Susan, hydrangea, yellow jessamine, and other wildflowers add color to the rural landscape. The state flower is the camellia. G Animal Life Few large mammals inhabit Alabama. The black bear is found in the swampy areas in the south, and white-tailed deer live in the northwest and southwest. There are some beaver colonies in central Alabama. Raccoon, opossum, weasel, otter, and a variety of rats, mice, rabbits, and foxes are common in most parts of the state. The muskrat and the southern woodchuck are also found in Alabama. Many species of birds have been identified in Alabama, including the bald eagle, the osprey, the northern harrier, the turkey vulture, the boat-tailed grackle, the purple gallinule, the long-billed marsh wren, and the seaside sparrow. The northern flicker, also known as the yellowhammer, is the state bird and the most common woodpecker found in Alabama. An important flyway for migratory waterfowl extends across Alabama from the Tennessee River valley to the Gulf Coast, and millions of ducks and geese winter on the bayous of the Mobile river delta and on the coastal marshes. Alligators, the largest reptiles in the state, are found in the southern swamps. Poisonous snakes found in Alabama are the copperhead, the cottonmouth (water moccasin), the rattlesnake, and the coral snake. In addition, there are many species of nonpoisonous snakes. Other reptiles include numerous varieties of turtles and lizards. Frogs are the most common amphibian. The lakes on the Tennessee and other rivers abound in bass, crappie, bream, and catfish. Along the Gulf Coast shrimps, pompano, tarpon, mullet, red snapper, crabs, and oysters are found. H Conservation Alabama's Department of Conservation and Natural Resources is responsible for control of air, water, and land pollution. It also deals with matters such as soil conservation and forest management. H1 Air Quality Air quality in most of Alabama is generally excellent. However, the federal standard for ozone is sometimes exceeded in the Birmingham metropolitan area. Air pollution problems include acid rain and toxic air pollutants such as heavy metals (lead, cadmium, mercury) and volatile organic chemicals. Most of the sulfur and nitrogen emissions that cause acid rain come from electric utilities. H2 Waste Management Alabama has been a major importer of hazardous waste, most of which has been sent to a commercial disposal facility near Emelle. A 1989 ban on hazardous waste imported from states that were unwilling or unable to undertake disposal programs was overturned in the early 1990s. In 2006 there were 13 hazardous waste sites on a national priority list for cleanup due to their severity or proximity to people. The state made progress in efforts to reduce pollution; in the period 1995-2000 it reduced the amount of toxic chemicals discharged into the environment by 29 percent. Most other states, however, achieved far more dramatic reductions than Alabama's. H3 Water Quality Groundwater is the source of drinking water for almost half the population and is an important source of water for agriculture and industry. Much of Alabama's groundwater is contaminated to a limited, and not unhealthful, extent. Contaminants include organic chemicals, nitrates, fluorides, brine and salt, metals, radioactive materials, and pesticides. The sources of contamination include municipal trash landfills and hazardous waste storage ponds and impoundments. III ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES From the early 19th century, Alabama's economy was dominated by one crop--cotton. After 1915, however, the boll weevil, a beetle that infests cotton plants, so damaged the state's cotton crop that farmers began to concentrate on raising livestock and crops other than cotton. Manufacturing began to be important to Alabama with the growth of the iron and steel industry during the early 20th century. Beginning in the 1930s low-cost power provided by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a federal agency, encouraged industrial development. In the late 1990s manufacturing remained the dominant economic sector. Also significantly contributing to Alabama's gross product were the government and service sectors. Alabama had a work force of 2,200,000 in 2006. The largest share of the jobs--33 percent--was in the service occupations, such as computer programming or catering. Another 18 percent of the workers were employed in wholesale or retail trade; 18 percent in manufacturing; 19 percent in federal, state, or local government, including those in the military; 6 percent in construction; 20 percent in transportation or public utilities; 16 percent in finance, insurance, or real estate; 2 percent in farming (including agricultural services), forestry, or fishing; and just 0.6 percent in mining. In 2005, 10 percent of Alabama's workers were unionized. A Agriculture In 2005 there were 43,500 farms in Alabama. Of those 32 percent had annual sales of more than $10,000; many of the rest were sidelines for operators who held other jobs. Farmland occupied 3.5 million hectares (8.6 million acres), of which 42 percent was cropland. Most of the remainder was pasture, although farmers kept some of their land as woodlots. The sale of livestock and livestock products accounted for 82 percent of the income generated on farms in 2004, with sales of crops accounting for the remainder. Alabama's livestock and animal products include chickens, particularly broilers (young chickens used for food); beef cattle; eggs; hogs; and milk. The state's chief crops are greenhouse and nursery products, peanuts, and cotton. Other crops raised in the state include hay, soybeans, corn, wheat, potatoes, oats, and sorghum. Some tobacco is grown, which is used in the manufacture of cigars. A1 Patterns of Farming The Tennessee River valley is the major cotton-growing area in the state, although soybeans, cattle, and winter-sown grains are also raised there. When fertilized, the sandy loams of the Cumberland Plateau yield good crops of cotton and corn; poultry and other livestock are an important source of income for farmers there. Peach, pear, and apple orchards dot the slopes of the Ridge and Valley province, and forests thrive on the Piedmont. Beef and dairy cattle graze on the lush grasslands that now cover the Black Belt, once a major cotton-growing area. In the southeast the most striking result of the cotton-boll weevil infestation during the first quarter of the 20th century was the shift from cotton growing to the cultivation of peanuts, soybeans, and corn. The farmers later introduced hogs to root over the peanut fields after harvesting. They also introduced cattle and chickens. In the southwest fruit and vegetables are cultivated. B Fisheries The total income from fishing is relatively small in Alabama, just $37 million in 2004. However, the coastal waters yield quantities of shrimps, oysters, crabs, pompano, mullet, snapper, and many other sea fishes. Fishing vessels take their catch to Mobile and to other Alabama ports to be processed in local canneries or to be shipped to markets that are located farther away. C Forestry Lumbering has been carried on in Alabama since about 1830, but until the 20th century no effort was made to plan for a continued yield through selective cutting and reforestation. After 1930 the production of wood products expanded rapidly, and pine forests now supply the greater part of Alabama's lumber, as well as valuable quantities of turpentine, tar, and rosin. Even scrub timber, once regarded as useless, is in demand for wood pulp, and many farmers sell such pulpwood to supplement their income. Tree farming is an important activity in Alabama. Fast-growing species, including several varieties of pine, are raised as crops and are harvested when mature, usually within five or seven years after being planted. With careful management even small tracts of woodland can provide a steady source of income for their owners. D Mining Mineral resources have given Alabama a commanding lead among the Southern states in the production of iron and steel. Within a radius of about 25 km (about 15 mi) of the city of Birmingham are found deposits of the three basic raw materials required for steel production: iron ore, limestone, and bituminous coal. By the late 1970s, however, no iron ore was being mined in Alabama, and that used in the steel industry came from outside the state. Natural gas is Alabama's most valuable mineral, generating more than one-half of the state's income from fossil fuels. Large deposits of bituminous coal are found in the northwestern section of the state, while deposits of lower-grade lignite are scattered around the coastal plain. Most of the coal extracted comes from underground mines, some of which are among the deepest in the United States. Tuscaloosa, Walker, and Jefferson are the leading coal-producing counties. Also important is petroleum, which along with natural gas comes mostly from wells in the southwestern counties of Mobile and Choctaw. By value, principal nonfuel minerals produced in Alabama are cement, crushed and broken stone, lime, and sand and gravel. The state ranks fourth in the nation in lime production, while it is first in common clays and second in kaolin, a high-fire clay. Some of the world's finest-grained marble is found in the Sylacauga area. E Manufacturing Manufacturing contributes more to personal income and more to the gross state product than any other economic sector in Alabama. In terms of the value added by manufacture, the leading industry in the state in 1996 was the manufacture of paper and associated products, with the leading employers in the sector being paper and pulp mills, producers of sanitary paper products, and firms making corrugated boxes. Other leading industries were chemical manufacturers, including those making chemicals for agriculture and other industries, organic fibers, and paints; primary metal manufacturers, including iron foundries, blast furnaces, and steel mills; firms making aluminum sheets and plates, and copper rolling mills; and textile mills, making woven cloths and yarns. Industries also employing a large number of Alabama residents are meatpackers; manufacturers of men's and boys' apparel; makers of vehicle tires; producers of motor vehicle parts; and lumber mills. The Birmingham area accounts for a significant portion of the manufacturing income and employment in Alabama. The production of iron and steel and the fabrication of cast-iron pipe and of metal valves and fittings are the area's leading industries. Beginning in the late 1970s, the area's iron and steel industry, buffeted by national economic recessions and foreign competition, suffered a tremendous decline. Many steel mills were closed permanently, and thousands of workers lost their jobs. However, some of the decline in the iron and steel industry was offset by growth in the fabricated metals industry. Huntsville has been the center for many developments in U.S. missile manufacturing. The United States Army's Redstone Arsenal and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's George C. Marshall Space Flight Center are in the Huntsville area. Reduced government spending on aerospace activities in the 1970s led the city to seek economic diversity. By the early 1990s, Huntsville had attracted almost 100 new manufacturing firms, many of them engaged in high-technology areas such as computer electronics. Mobile is an important center for the manufacture of paper products and chemicals. Its chemical industry produces fertilizer, paint, and varnish. Ship repair is also significant in the Mobile area. F Electricity Both public and private enterprise have provided for the harnessing of Alabama's rivers to produce electricity. Beginning in 1916, a series of massive dams was constructed, including Wheeler Dam and Wilson Dam, both near Muscle Shoals, and Guntersville Dam. These and other dams were acquired by the TVA in the 1930s. In the second half of the 20th century both the TVA and private utilities have greatly expanded their facilities. In 2005, 67 percent of the electricity generated in Alabama came from steam-driven power plants burning fossil fuels, mainly coal; 23 percent came from nuclear power plants; and the rest came from hydroelectric power plants. In the 1970s five nuclear power plants went into operation, three at Decatur and two at Dothan. G Transportation Birmingham, Montgomery, and Mobile are the chief transportation centers of Alabama. Birmingham is the principal railroad junction and is a focus of several major highways, as are Montgomery and Mobile. In 2007 the airport in Birmingham was the busiest of the state's 10 airports. In 2005 Alabama was served by 154,571 km (96,046 mi) of highways, including 1,463 km (909 mi) of the federal interstate highway system. A dense network of railroads extended for 5,362 km (3,332 mi). Some 27 percent of the tonnage of goods hauled by rail and originating in the state was coal, while another 12 percent was wood products such as pulp, paper, or lumber. Mobile, the state's only major seaport, is one of the leading ports in the South. The south's largest bulk coal export facility, and the country's second largest, is located at the Alabama State Dock. Other products imported and exported include iron ore, grain, gypsum, copper slag, and more forest products than any other U.S. port on the Gulf of Mexico. Mobile lies on the Gulf portion of the Intracoastal Waterway, which extends along the coast from western Florida to the Mexican border. Mobile is also linked with other industrial cities by the Black Warrior, Alabama, and Chattahoochee rivers, which carry a heavy barge traffic in pulpwood, coal, oil products, iron and steel goods, cotton, and chemicals. The Tennessee River is also a major transportation route for barge traffic. In 1985 construction was completed on the TennesseeTombigbee Waterway, which links the two rivers by means of a canal in northern Mississippi. The waterway provides a shorter water route from the inland eastern states to the Gulf of Mexico at Mobile. IV THE PEOPLE OF ALABAMA A Population Patterns According to the 2000 national census, Alabama had a population of 4,447,100 inhabitants, ranking it 23rd among the states. The population was an increase of 10.1 percent over that recorded in the 1990 census. The average population density in 2006 was 35 people per sq km (91 per sq mi). Whites make up the largest share of the state's population at 71.1 percent of the people. However, at 26 percent, the share of blacks in the state is among the highest in the nation. Some 0.7 percent of the people are Asians, 0.5 percent are Native Americans, and 1.6 percent are of mixed heritage or did not report race. Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders number 1,409. Hispanics, who may be of any race, are 1.7 percent of the people. The black population is largely concentrated in the larger cities and in the central and southern counties. Blacks make up about three-fourths of the total population in Greene, Lowndes, and Macon counties. Comparatively fewer blacks live in the northern counties. B Principal Cities In 2000, 55 percent of the state's inhabitants lived in cities, towns, and villages of more than 2,500 people. The largest cities are Birmingham, Montgomery, Mobile, and Huntsville. Birmingham, the largest with 229,424 inhabitants in 2006, is set in a long valley flanking Red Mountain. It is known as the Pittsburgh of the South for its complex of skyscrapers, steel mills, factories, and railroad yards. Montgomery, the state capital, had a population of 201,998. It is an important manufacturing city and a marketplace for lumber and cattle. Mobile has 192,830 inhabitants and is an industrial center and seaport whose tree-lined streets and historic buildings evoke its French and Spanish past. Huntsville had 168,132 people. It is a major aerospace center. Other major cities include Tuscaloosa, Dothan, Decatur, Gadsen, Florence, Prichard, Bessemer, and Anniston. C Religion More than 90 percent of all church members in Alabama are Protestants. About 5 percent are Roman Catholics, and less than 1 percent are Jewish. Among the Protestant congregations the Baptists and Methodists have the largest memberships. V A EDUCATION AND CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS Education The first school in Alabama was opened near Mobile in 1799. It was followed by the Washington Academy at Saint Stephens in 1811. A statewide public school system did not go into effect, however, until 1854, after an experimental system in Mobile had proved successful. Serious efforts to support the schools attained marked results only after 1900. Separate schools were maintained for white and black children until the early 1960s, when desegregation began under court order. State law requires all children from ages 7 to 16 to attend school. Some 10 percent of Alabama's children attend private schools. In the 2002-2003 school year Alabama spent $7,031 on each student's education, compared to a national average of $9,299. There were 12.6 students for every teacher (the national norm was 15.9 students). Of those older than 25 years of age in the state in 2006, 80.1 percent had a high school diploma, while the nation as a whole averaged 84.1 percent. A1 Higher Education The University of Alabama, the main campus of which is in Tuscaloosa, is the principal state university. Other major institutions are Auburn University (1856), the oldest land-grant institution in the South and home of the state's largest agricultural and engineering colleges, and Tuskegee University, an historically black school. In 2004-2005 Alabama had 42 public and 27 private institutions of higher education. B Libraries Alabama has 207 public library systems. Each year libraries circulate an average of 3.8 books for every resident. The department of archives and history in Montgomery was one of the first libraries in the country to be incorporated as part of a state government. An outstanding collection of reference material on the history and culture of Alabama is in the W. S. Hoole Special Collections Library at the University of Alabama. C Museums Notable museums include the Birmingham Museum of Art, the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, the Alabama Museum of Natural History at the University of Alabama, the George Washington Carver Museum at Tuskegee University, the Anniston Museum of Natural History, the Mobile Museum of Art, and the United States Army Aviation Museum at Fort Rucker. The Berman Museum of World History in Anniston exhibits more than 3,000 historical objects, art, and weapons spanning 3,500 years, many belonging to prominent historical figures such as Abbas I, Emperor Charles V, Napoleon I, and Jefferson Davis. The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute has exhibits that depict historical events from racial separation in the 1920s to present-day racial progress. D Communications In 2002, 20 daily newspapers were published in Alabama. The first-known newspaper was the Mobile Centinel, printed at Fort Stoddert in 1811. The Mobile Register, founded as the Gazette in 1813, is Alabama's oldest continuously published newspaper. Other influential dailies include the Birmingham News, the Birmingham PostHerald, the Huntsville Times, and the Montgomery Advertiser. The first radio station in the state, WBRC in Birmingham, was licensed in 1925, and the first television station, WAFM-TV in Birmingham, was licensed in 1949. In 1955 Alabama began to run the nation's first state-owned educational television network. In 2002 Alabama was served by a comprehensive communications system, which included 113 AM radio stations, 116 FM radio stations, and 37 television stations. E Architecture In Mobile and other early Alabamian towns the style of architecture reflected French, English, and Spanish influences. French design was predominant, particularly the French Colonial and Creole styles. Ornamental ironwork for houses and public buildings became popular in the 1780s. Between 1820 and 1850, a period of great prosperity for cotton planters, many elegant plantation homes were built or remodeled in the Greek Revival style. Fine examples of Greek Revival architecture include the President's Mansion at the University of Alabama and the Battle-Friedman House, also in Tuscaloosa. F Music Alabama has several symphony orchestras. Mobile, Montgomery, Huntsville, and Muscle Shoals have civic societies that arrange for concerts and ballet performances. There are opera companies and music societies in Birmingham, Huntsville, and Mobile. The Alabama Shakespeare Festival features year-round performances. Interest in classical music in Alabama was first centered in Mobile, where amateur music groups flourished during the 1850s. Folk music has long been a part of the cultural life of Alabamians. Day-long singing meetings, called singings, are still popular in the mountains of Alabama. The black spirituals and blues that developed in the Alabama lowlands and in other areas of the South are now considered a distinctly American form of music. VI RECREATION AND PLACES OF INTEREST Alabama has many recreational facilities and places of scenic and historic interest. In northern Alabama, reservoirs attract thousands of fishing enthusiasts each year. Fishing and other water sports also lure visitors along the Gulf of Mexico. A National Parks Most of the units administered by the National Park Service are linked to Alabama's rich history. Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site preserves some of the institute's original brick buildings as well as the home of Booker T. Washington, who in 1881 founded the noted college for blacks. The school today remains an active university that owns most of the property within the national historic site. Horseshoe Bend National Military Park is the site where in 1814 the forces of General Andrew Jackson broke the power of the Upper Creek alliance of Native Americans and opened large parts of Alabama and Georgia to settlement. In the northeastern corner of Alabama is Russell Cave National Monument. A small cave there served as a home for Native Americans for a span of more than 8,000 years. A small portion of the Natchez Trace Parkway crosses northwestern Alabama on its route between Nashville, Tennessee, and Natchez, Mississippi. The parkway generally follows a trail first established by Native Americans and later heavily used by early settlers. Little River Canyon National Preserve is noted for its spectacular landscapes and canyons created by the river. B National Forests There are four national forests in Alabama. The largest forest is Talladega National Forest, which is made up of one section in west central Alabama and another, a mountainous section, in northeastern Alabama. The northeastern section encircles Cheaha State Park, which is the site of Cheaha Mountain, the highest point in the state. William B. Bankhead National Forest is located in northwestern Alabama. Conecuh National Forest is situated in southern Alabama. The smallest of Alabama's national forests is Tuskegee National Forest, which is situated in the eastern part of the state. C State Parks Alabama's state park system offers a great variety of scenic and recreational attractions. DeSoto State Park, not far from Fort Payne, is the site of one of the deepest canyons east of the Mississippi River. At Huntsville is Monte Sano State Park, which lies on the crest of Monte Sano and includes Natural Well, a great circular hole whose depth has never been determined. Cheaha State Park, near Anniston, is surrounded by Talladega National Forest. The largest state park is Oak Mountain State Park, which covers an area of 4,023 hectares (9,940 acres). It is located near Birmingham. Gulf State Park lies on Alabama's Gulf Coast southeast of Mobile. Rickwood Caverns State Park, located at Warrior, north of Birmingham, is known for its underground caverns, with limestone formations believed to be 260 million years old, and its underground pools. D Other Places to Visit The Ave Maria Grotto, located at Southern Benedictine College near Cullman, contains miniature reproductions of the Vatican and of temples, mosques, and churches from around the world. Bellingrath Gardens, set on a bluff near Mobile, are filled with thousands of colorful flowering plants. The Boll Weevil Monument, at Enterprise, was erected "in profound appreciation of the boll weevil, and what it has done to herald prosperity," after the insect had destroyed most of the 1910 cotton crop and farmers had turned as a result to the cultivation of peanuts. Birmingham's Arlington Antebellum Home and Gardens, used as headquarters by General J. H. Wilson in his raid through the state in 1865, is one of the most frequently visited sites associated with the American Civil War (1861-1865). Another is the First White House of the Confederacy in Montgomery, the home of President Jefferson Davis during the early months of the Confederacy. The State Capitol in Montgomery is considered to be one of the most beautiful in the nation. It served as the first capitol of the Confederacy. Ivy Green, an ivy-covered frame cottage in Tuscumbia, was the birthplace and childhood home of Helen Keller, the renowned author and lecturer. A huge statue of Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and the patron of metalworkers, stands on Red Mountain overlooking the city of Birmingham. The 17-m (55-ft) statue is mounted on a 37-m (120-ft) tower and is said to be the largest iron statue in the world. The battleship Alabama, anchored in Mobile Bay and open to the public, attracts many visitors. The Civil Rights Memorial, in Montgomery, honors 40 people who lost their lives in support of the civil rights movement between 1954 and 1968. The monument was designed by architect Maya Lin, who also designed the Vietnam Veteran's Memorial in Washington, D.C. E Annual Events Mardi Gras is a legal holiday in Alabama. It is celebrated in Mobile by an annual five-day carnival ending traditionally on Shrove Tuesday. Another popular event is the Azalea Spectacular, a flower festival held in Mobile in February or March. A similar festival, the annual Birmingham Rose Show, is held in May. Classic plays are staged each summer at the Alabama Shakespeare Festival at Anniston. Annual sporting events include the Alabama Shooting Trials, held at Union Springs in the fall, and the River Boat Regatta, held at Guntersville in August. Three postseason college football games, the Senior Bowl, the Hall of Fame Bowl, and the Blue-Gray Classic, are played annually at Mobile, Birmingham, and Montgomery, respectively. Two major automobile races are held each year at the Talladega Superspeedway. F Sports Alabama has a strong tradition of college football. It is the home of one of the nation's most intense intrastate rivalries, that between Auburn University and the University of Alabama. Notable sports personalities from Alabama colleges include football coach Bear Bryant, football players Joe Namath and Bo Jackson, basketball player Charles Barkley, and track star Jesse Owens, winner of four gold medals during the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. VII GOVERNMENT Alabama's present constitution was adopted in 1901 and is the sixth constitution since 1819, the year of Alabama's admission to the Union. To become law, a proposed amendment must receive a three-fifths majority vote in each house of the state legislature and then a majority vote of the electorate. A Executive The executive branch of the state government is headed by a governor elected for a term of four years. Governors cannot hold any other state office or serve in the United States Senate during their terms as governor or for one year after their terms end. The governor may serve two consecutive terms. The governor may veto legislation and items in appropriation bills, but the veto may be overridden by a majority vote of the elected membership of each house of the legislature. Other state executive officers include the lieutenant governor, secretary of state, attorney general, auditor, treasurer, and commissioner of agriculture and industries. Each is elected for a four-year term and may serve consecutive terms. B Legislative The state legislature consists of a Senate of 35 members and a House of Representatives of 105 members. Senators and representatives are elected for four-year terms. The legislature meets for an annual session of 30 legislative days. C Judicial The supreme court of Alabama is composed of a chief justice and eight associate justices. It hears appeals in criminal cases involving a prison sentence of more than 20 years and in civil cases involving more than $1,000. All other appeals are heard by a court of criminal appeals or a court of civil appeals. The major trial courts are the circuit courts. All judges are elected to six-year terms. D Local Government Each of Alabama's 67 counties has a governing body that administers county affairs as prescribed by state law. The principal officers in each county are the probate judge, sheriff, coroner, tax assessor, tax collector, clerk of the county court, superintendent of education, pensions and security director, health officials, and engineer. Most towns and cities in the state have the mayor and council form of municipal government. However, many of the larger cities have the commission form of government, and a few communities are governed under the city manager form of government. E National Representation Alabama elects two U.S. senators and seven members of the U.S. House of Representatives. The state casts nine electoral votes in U.S. presidential elections. VIII HISTORY A Early Inhabitants Hunter-gatherers were the earliest inhabitants of the area now called Alabama. Excavations at Russell Cave have revealed that Native Americans dwelled in northeastern Alabama more than 8,000 years ago, and many archaeological sites suggest that people lived in Alabama 2,000 to 3,000 years before that. Later, highly organized groups, called Mound Builders for the ceremonial earthen platforms they built, lived in the Alabama, Tombigbee, and Black Warrior river valleys. When Europeans first came in the 16th century, Alabama was well populated. The local Native American nations had highly developed sociopolitical groups with complex trade and family networks. Central locations, often stockaded towns, were hubs of economic, social, religious, and political activity. Agriculture centered around the cultivation of beans, corn, and squash. The pottery, stone carvings, and metalwork of these peoples show sophisticated artistic skill and complex symbolic systems. B The Spanish Expeditions The first Europeans to reach Alabama were Spanish explorers looking for gold. Alonso Alvarez de Piñeda and Pánfilo de Narváez explored the coast early in the 16th century. The first expedition into the interior was led by Hernando de Soto, starting in 1539. With a force of several hundred soldiers, de Soto intended to find and conquer a kingdom rich in gold that he believed existed in the region. De Soto used coercion, raiding villages and taking hostages, to try to get information about the golden kingdom, as well as food and supplies. News of his tactics preceded him, so that he met resistance along most of his route and had to fight several battles. At Mauvila, a village on the Alabama River, de Soto's forces fought and defeated Chief Tascaluza and his warriors. The Spanish explorers then marched west into Mississippi, but their numbers were much reduced by battle casualties, disease, and hunger. They were harassed by sporadic attacks, and were denied food and medicine that might well have been shared with them if they had come in peace. De Soto died near the Mississippi River, and only a small number of his force survived to return in 1543 to Mexico, their starting point. They never found gold, and they decided the golden kingdom was a myth. They left behind some mixed-blood children and several European diseases. In 1559 Don Tristán de Luna, with 500 soldiers and 1,000 Spanish colonists from Mexico, arrived in Mobile Bay to start a settlement. However, a storm destroyed many of their supplies, and starvation forced them to abandon the colony and return to Mexico. The Spanish made no further effort to settle the area, but their horses, hogs, and cattle were adopted by the local population. The Native Americans had no immunity to the new diseases brought by the Europeans, and their societies were drastically changed. Thousands of people became ill and died. Many towns and villages were abandoned. The survivors merged into larger groups, so that by the 18th century few of the peoples that de Soto met were still organized under the same names. Most of the native Alabamians became members of four major Native American nations: the Cherokee in the north, the Chickasaw in the northwest, the Choctaw in the southwest, and the Creek Confederacy in the center and southeast. These nations for many years dealt with the Spanish, French, British, and Americans, forming alliances according to their own best interests. C Colonial Rule C1 French Colonization The first successful European colonizers in Alabama were the French. In 1682 they claimed the huge land they called Louisiane (in English, Louisiana), which extended from the Gulf Coast to Canada and included Alabama. The first French settlements were fortified trading posts. The first one in Alabama was Fort Louis de la Louisiane, commonly called La Mobile, built in 1702 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, on the Mobile River at Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff. This fort was the seat of French government for Louisiana until 1711, when Bienville moved the colony downriver to the site of present-day Mobile. Called Fort Condé, this settlement was the capital until 1719, when the seat of government was moved into present-day Mississippi. Meanwhile, settlers arrived from France and Canada. Black slaves were introduced to clear the fields after 1719. Through their hard labor, large areas of land were cleared to raise food for the soldiers and settlers as they searched for products that could be sold to support the colony. French traders moved inland, building Fort Toulouse (1717) at the meeting of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers and Fort de Tombecbé (1736) on the Tombigbee River. Traders from Great Britain, who were rivals of the French and disputed the boundary of Louisiana, arrived in Alabama from South Carolina and later from their new colony, Georgia. The British built Fort Okfuskee on the upper Tallapoosa. French influence waned as the Native Americans learned that British traders offered better products than the French and demanded fewer deerskins in exchange. C2 Shifting Boundaries Great Britain and France fought a series of wars in the 18th century that climaxed with the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Great Britain was the decisive winner and concluded a peace treaty that removed the French from the North American continent. Mobile was incorporated into West Florida, a colony that Spain ceded to Great Britain in 1763. All of Alabama north of West Florida became part of the Lands Reserved for the Indians, administered by a British superintendent for Native American affairs. White settlement in this reservation without the permission of the Native Americans was forbidden by the king's order. British colonists who lived on the frontier resented the ban on settlement. They felt this was an arbitrary infringement on the original colonial grants, most of which had vague or unlimited western boundaries. During the American Revolution (1775-1783), the Cherokee and Creek supported the British against the Americans. The Spanish, who supported the Americans, captured Mobile in 1780 over British and Native American resistance. At the end of the revolution, West Florida was returned to Spain and interior Alabama was turned over to the United States. Georgia claimed most of Alabama as part of its original grant. Settlers from Georgia encroached on the lands of the Native Americans, who sought Spain's help to keep them out. Spain, however, was reluctant to support them against the growing power of the United States. For several years the United States and Spain disputed the southern boundary of the United States. Finally, in 1795, the two countries agreed on a boundary at latitude 31° North. That line still forms most of the border between Alabama and Florida. Three years later, the Congress of the United States created Mississippi Territory, comprising most of present-day Mississippi and Alabama. The Mobile area remained Spanish until U.S. General James Wilkinson captured it in 1813. D The 19th Century D1 The Creek War In 1800 nearly all of Alabama north of 31° north latitude was still controlled by Native Americans, but that soon changed. After the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the federal government built the Federal Road to connect the new territory with the national capital at Washington, D.C. The road ran through Creek territory from Athens, Georgia, to Fort Stoddert, north of Mobile. For the first time, access from the east was relatively easy. Settlers came to Alabama by the thousands, further crowding the Native Americans. On June 18, 1812, the War of 1812 broke out between the United States and Britain. Spain let the British Navy operate from Florida, which is why Wilkinson captured Mobile. The Upper or Northern Creek, angered at the Americans intruding on their land, took the British side. On August 30, 1813, an Upper Creek war party attacked and overran Fort Mims, the stockaded home of Sam Mims, where frontier settlers and mixed-blood families had gathered for protection from Upper Creek marauders. About 250 people were killed at Fort Mims, although rumor and newspaper reports doubled the figure. American militias along the frontier rallied, and the Tennessee Volunteers under General Andrew Jackson moved south and destroyed Creek villages. On March 27, 1814, Jackson's forces decisively defeated the Upper Creek at the battle of Horseshoe Bend on the Tallapoosa. They were forced to sign a treaty with Jackson surrendering part of their land. Over the next five years the Creek and their allies were forced to cede much more land in central and southern Alabama. D2 Statehood By 1817 so many white settlers had migrated into the eastern (Alabama) part of Mississippi Territory that they seemed likely to get political control of the whole territory. Citizens living along the Mississippi River, who had dominated the territorial government until then, were eager to separate from the Alabama portion. Thus, when Mississippi became a state in 1817, Alabama became a separate territory with its capital at Saint Stephens. On December 14, 1819, it was admitted to the federal Union as the 22nd state. Territorial Governor William Wyatt Bibb became the first governor of the state. Almost immediately, rivalry between north and south Alabama began to flavor Alabama politics and complicate the location of a capital. Huntsville was the temporary capital until Cahawba (Cahaba), more or less centrally located in Dallas County, was built in 1820. In 1826, however, the capital was moved to Tuscaloosa, and again, in 1846, to Montgomery, where it remained. Sectionalism continued over such issues as apportionment of the legislature, location of the state university, and election of U.S. senators, and was still important in the late 20th century. Alabama's first years of statehood were marked by an influx of settlers from Tennessee, South Carolina, and North Carolina. The population more than doubled, from 127,901 in 1820 to 309,527 in 1830. Small subsistence farms and large cotton plantations were established in the fertile dark-soiled Black Belt and the Tennessee Valley. Caravans of slaves, mules, and household goods lined the roads and trails into the state. Pressure intensified on Native American enclaves, especially those of the Creek in eastern Alabama. During the administration of Andrew Jackson as U.S. president (1829-1837), these nations were forced to give up their lands and move west of the Mississippi. Some remained, however, particularly those who had adopted white culture and claimed individual parcels of land. Meanwhile, cotton production became the way to make fortunes in Alabama. Driven by the cotton boom, planters bought land and slaves on credit, and sold their crops through factors who shipped them to Mobile or New Orleans. To grow cotton, Alabama adopted the plantation system, organized around slave labor, that had been developed in Virginia. Thus the slave population of the state grew 270 percent from 1830 to 1860, compared with 171 percent for the white population. A lifestyle based on cotton wealth developed, and an elite group of wealthy planters dominated Alabama society. Despite their influence, however, slaveowners were a small minority (6.4 percent of the white population in 1860) and did not control the votes of the common people. The mostly nonslaveowning small farmers of the hill country, the mountains, and the Wiregrass region (in the southeastern corner of the state) dominated statewide elections. They were not commercial farmers interested in the price of cotton on the world market. They were largely adherents of Jackson's Democratic Party, favoring local control, equality of opportunity, and dispersal of economic power. They also tended to be hostile to private banks, which they distrusted as concentrations of economic power. Consequently, because Alabama faced a shortage of capital, the legislature established a state bank in 1824. However, mismanagement and political interference weakened the bank, and the nationwide economic slump of 1837 devastated its solvency. The issue of bank reform dominated state politics for years before the state bank was finally liquidated in the 1840s. D3 The Alabama Platform Slavery was one of the most divisive political issues in the U.S. Congress during the first half of the 19th century. Many senators and congressmen from the Northern states pressed to end slavery, both because it was considered immoral and because white labor could not compete with unpaid black labor. Members of Congress from the Southern states, including Alabama, believed that slavery was essential to their agricultural system and that the North was trying to dominate the national economy. The South could resist attempts to change its system as long as Congress was about equally divided between slave states and free states. Thus the South was vitally interested in maintaining that balance. In 1846 Congress debated the Wilmot Proviso, which would have closed to slavery all territories gained in the Mexican War (1846-1848). Southerners were alarmed because this meant that several new free states would be created; the balance would be destroyed. Sectional tension rose to a furor. William L. Yancey of Montgomery became a leader of the Southern radicals, who were known as fire-eaters. Yancey advocated secession from the Union and formation of a separate Southern nation. He led the "Southern rights" wing of the Alabama Democratic Party and persuaded the state party to adopt his Alabama Platform. This document declared that the federal government was obligated to protect slavery in the territories and that a slaveowner had a right to take his slave property anywhere in the territories. In the 1850s many Alabamians came to believe that secession was the only way to protect what they believed were Southern rights, including the right to own slaves. They were in the minority, however, until 1860. That year, Abraham Lincoln was elected president as the candidate of the Republican Party, which opposed the spread of slavery. The Southern state of South Carolina had threatened to secede if the Republicans won the presidency, and in December 1860 it did so. Other Southern states began to follow. In Alabama, a convention was called in Montgomery to consider the question. Despite strong Unionist sentiment in north Alabama and the Wiregrass, the convention voted for secession on January 11. Alabama was the fourth state, after South Carolina, Mississippi, and Florida, to leave the Union. Alabama invited six other seceding states to a meeting in Montgomery in February 1861 to consider forming a Southern nation. At that meeting they established a confederacy, the Confederate States of America, and elected as their president Jefferson Davis, a Mississippi planter, U.S. Military Academy graduate, and former U.S. senator and secretary of war. Davis took the oath of office on the main portico of the Alabama state capitol. Montgomery became the first capital of the Confederacy, but in May, for political, military, and economic reasons, the capital was moved to Richmond, Virginia. D4 Civil War Although Union support remained strong in the north hill country and mountains, most Alabamians supported the Confederacy in the American Civil War (1861-1865) that followed. Union forces invaded several times and occupied parts of north Alabama, but the most important military action of the war in Alabama was the naval Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864. Union Admiral David G. Farragut easily defeated the outgunned Confederate navy that defended the bay. However, the city of Mobile itself was not captured until April 1865. Union cavalry raids swept through the state late in the war and caused devastation, although not on the same scale as was inflicted on Georgia. D5 The Reconstruction Period The Confederacy surrendered in 1865, and Union troops were stationed in the Southern states. Alabama attempted to reestablish state government under the lenient terms that President Andrew Johnson offered for restoration, or Reconstruction, of the union. However, Congress imposed harsher terms: among other requirements, each state had to ratify the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which extended citizenship and civil rights to blacks. The Alabama legislature refused, and in 1867 Alabama was placed under military rule, as were nine other Southern states. A new voter registration excluded many former Confederates. Northerners and pro-Union Southerners, called respectively carpetbaggers and scalawags by their enemies, joined with blacks to form the state Republican Party and take control of the government. The new government adopted a new state constitution, and Alabama was readmitted to the Union in 1868. The Reconstruction government, despite much corruption, had some positive effects on Alabama. Railroads were built, industrial communities such as Birmingham emerged, and lumbering expanded. A federal agency, the Freedmen's Bureau, took responsibility for furnishing food and medical supplies to blacks, most of whom were destitute, and to needy whites as well. It was also concerned with the regulation of wages and working conditions of blacks and the establishment and maintenance of schools for illiterate former slaves. In addition, the bureau handled legal trials involving blacks. Most of the activities of the bureau were ended in 1869, except for the educational program, which continued until 1872. Many whites opposed military occupation and rule by carpetbaggers and scalawags based on black votes. The Ku Klux Klan and similar violent groups were organized to intimidate blacks and Republicans. Because of the violence, which drove both black and white Republicans from the polls, but also because of the high taxes imposed by the ambitious Reconstruction government, the Democrats regained control of state government in 1874. This ended Reconstruction in Alabama. D6 Bourbon Rule and Agrarian Unrest The Democrats, called Bourbons, who took over in 1874 inherited a large state debt, much of it fraudulent, that the Reconstruction government had incurred to finance expansion of railroads, industry, and public education. To cut back on the debt, they adopted a program of low taxes and limited spending. Education was underfunded, and school terms were little more than three months in rural areas. Black men continued to cast election ballots (no women of any race were allowed to vote) although the black vote was usually manipulated by whites through intimidation or economic pressure. With slavery abolished, blacks and whites had to adjust to wage labor. Most blacks and many poor whites had no land of their own. They had to work for large landowners, who had little cash to pay them. Under these conditions, a system of sharecropping and tenant farming evolved. A sharecropper raised part of the landlord's crop and was paid a share of the profit after deductions for living expenses and the cost of tools and supplies. A tenant farmer sold what he raised and paid rent to the landlord out of the profit. If the profit was low, the landlord got his share first. The sharecropper or tenant took what was left or, if none was left, got an advance to keep going for another year. The lenders who advanced credit usually demanded that the debtor farmers plant cotton, the South's most dependable cash crop. Unfortunately, the price of cotton fell soon after the Civil War and stayed down for decades. Thus the tenant farmers and sharecroppers fell into an endless cycle of debt. Cotton became even more dominant, and Alabama's agriculture and economic activity failed to diversify. Laws were passed limiting the freedom of sharecroppers and tenant farmers and restricting their economic opportunities. For instance, they forfeited any share in crops they abandoned, and their personal property could be seized by the landlord for unpaid debts. Not until World War II (1939-1945), when widespread mechanization of cotton production made sharecropping and tenant farming unprofitable for the landlords, did the system begin to disappear. The agricultural slump was not limited to cotton. As elsewhere in the nation, small farmers suffered as wealth created by commerce and manufacturing was concentrated in the hands of a few business leaders. Among the causes of unrest were the declining prices of farm products, the growing indebtedness of farmers to merchants and banks, and the discriminatory freight rates imposed on farmers by the railroads. In the 1870s and 1880s American farmers under midwestern leadership formed self-help groups such as the Grange and Farmers' Alliance. When these organizations decided that agricultural grievances had to be addressed with political action, the dominance of the Bourbons in Alabama was threatened. This threat was complicated by the fact that the Bourbons stood for white power, while the farmers' groups were willing to attract black farmers to their cause. The movement nationwide was called populism. Alabama populists tried first to gain control of the Democratic Party, and, when that failed, formed a splinter group, the Jeffersonian Democrats. The coalition of black and white farmers fell apart after 1896 as a result of intimidation and white susceptibility to racist Democratic appeals. Segregation of the races, through separate public facilities for whites and blacks, became a basic rule in Southern society in the last two decades of the 19th century. A black educator, Booker T. Washington of Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama, reacted to this erosion of black rights by advocating a policy of racial accommodation. He urged blacks not to emphasize the goals of social integration and political rights but instead to acquire the occupational skills that would lead to economic advancement. Other black leaders disagreed, but Washington's prestige and white support of his position caused him to be accepted as the blacks' chief spokesperson. E The 20th Century E1 New Industry By 1900 iron and steel were the most important industries in the state. United States Steel Corporation moved into the Birmingham district in 1907, indicating its national significance. Lumbering and turpentine production also became important. Industrial growth was due in large part to the building of railroads. The value of the state's few rail lines had come to be fully appreciated in the Civil War, when starvation was widespread because food produced in the Black Belt could not be transported into the hill country and other areas not served by navigable rivers. After the war, the Reconstruction government was determined to construct railroads, especially through the mineral district. The South also had come to appreciate an industrial economy. The coal, iron ore, and limestone deposits in Jefferson County, which had long been known but ignored, were now exploited. As railroads opened up the hill country, new towns based on industry--Birmingham, Anniston, Gadsden, and Fort Payne--grew into cities. During World War I (1914-1918) industrial and agricultural production in Alabama expanded to meet wartime needs. Mobile for a while became an important shipbuilding city despite the shallowness of Mobile Bay. The federal government spent millions of dollars clearing and keeping open the 58-km (36.5-mi) ship channel from Mobile to the Gulf of Mexico. E2 Diversification Economic expansion continued through the 1920s but was temporarily halted by the Great Depression of the 1930s. Alabama's delegation in Congress, which had much seniority and legislative experience, provided leadership for the economic recovery programs of the New Deal of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-1945). These federal programs helped ease poverty in Alabama and diversify the state's economy. One of the most important was the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which provided agricultural research (especially in improvement of fertilizers), reforestation, flood control, dam building, and hydroelectric power. South Alabama's mild climate and flat, gently rolling countryside made it attractive for military bases and airfields. Military expenditures during World War II stimulated economic expansion and provided civilian jobs. Mobile again became an important shipbuilding center, and the Birmingham steel plants geared up for war production. Alabama's economic base continued to diversify after World War II. Beginning in the 1950s, the U.S. spaceflight program at Redstone Arsenal and George C. Marshall Space Flight Center made Huntsville a leading aerospace center. Birmingham's economy, which had depended heavily on the iron and steel industries and blue-collar labor, saw growth in medical services, insurance, manufacturing, and engineering. Labor unions became less important, but not before wages increased. Alabama farmers turned to cattle, timber, soybeans, peanuts, and chickens, while cotton production fell. Through the 1970s, the rural population and the number of farms decreased as people moved to urban areas. The remaining farms were mostly large agribusinesses. E3 Political Developments, 1900 to 1972 Populism, with its potential to combine poor-white and black interests, threatened Bourbon control of Southern state governments. The Bourbons' response was to disfranchise blacks--that is, prevent them from voting. Mississippi was the first state to disfranchise black voters. Alabama achieved it through its 1901 constitution, using methods like a property ownership requirement, a literacy test, and a poll tax (a tax levied on individuals as a prerequisite for voting). In one-party Alabama, the Democratic nomination was equivalent to election, so early in the 20th century, nominating conventions were replaced by direct primary elections. This gave the people greater power in selecting candidates. In the years preceding World War I, several reforms and new laws were enacted. Governor Braxton Bragg Comer (1907-1911) achieved regulation of child labor in factories, better funding of education, and stronger regulation of railroads. After World War I, a state budgetary system was introduced, and the tax structure was revised to provide more revenue. State highway construction was expanded as automobile traffic increased. Bibb Graves was elected governor in 1927 with the support of the Ku Klux Klan, which was then politically powerful in Alabama. Graves brought many progressive reforms, including abolition of the corrupt and inhumane convict lease system. This system amounted to slavery: convicts were put to work in chain gangs for private entrepreneurs who had contracted with the state for their labor in fields, mines, or road repair. They were never paid for their labor, thus leaving large profits for the business owners and the state. Graves also improved mental hospitals and provided capital improvement funds for schools and colleges. The onset of the Great Depression forced Graves to deal with relief for Alabama citizens who were suffering from the hard times. He campaigned on promises to provide jobs in state government when he ran for governor again in 1935 (at that time the constitution did not allow governors to succeed themselves). In his second term, New Deal programs such as the TVA helped ease the Depression in Alabama. In 1939, after Governor Frank M. Dixon took office, a state civil service was established to provide a fair, rational basis for filling state government jobs. This was a reaction to Graves's use of state jobs as a campaign ploy and his granting of jobs for political purposes. Later Dixon reorganized the state government and streamlined its cumbersome system of expenditure. James E. ("Big Jim") Folsom, who was governor from 1947 to 1951 and from 1955 to 1959, was very popular and was noted for his colorful campaigning style. He campaigned in small towns and crossroads hamlets from a wagon filled with hay, and his speeches were preceded by music from his "Strawberry Pickers" country music band. As he talked, he swirled a mop in a bucket of suds, saying he would use the mop to clean up state government. Folsom was more liberal on racial questions than other Alabama politicians of his time. He opposed oppressive segregation policies and refused to tolerate terrorism by the Ku Klux Klan. One of Folsom's supporters was a Barber County state legislator, George C. Wallace, who tried to succeed him in 1959. Race was a main issue in the campaign, and Wallace's opponent, John Patterson, used it to win votes (most blacks were still unable to vote). Wallace, following Folsom's example, did not use race as an issue, and it cost him the election. In 1962, however, Wallace ran on a platform of support for segregation and made race the cornerstone of his campaign. This time he won easily. In 1966 he supported the election of his wife, Lurleen, to carry on his policies until he was eligible for another term. Two years into office, however, she died of cancer. In 1968 Wallace ran for president of the United States as the candidate of the American Independent Party. Campaigning on a platform of states' rights and "law and order," he carried Alabama and four other Southern states. In 1970 Wallace was again elected as governor, and in 1972 he campaigned for the presidential nomination of the Democratic Party. During a speech in Laurel, Maryland, he was shot and partially paralyzed by a would-be assassin. In 1974 he became governor again after the law was changed to let him succeed himself. He thus became the first Alabama governor to serve three terms. E4 Civil Rights After Reconstruction, Alabama maintained separate schools and other public facilities for whites and blacks. During the 1950s and 1960s, civil rights activities in the state focused on integration of these facilities and equal political rights for blacks. The federal government encouraged these efforts, but most white Alabamians supported the state's segregation policies and state officials continued to enforce them. The intransigence of Alabama officials encouraged civil rights groups to challenge state authority, and Alabama witnessed a number of major events of the period. In 1955 a black woman named Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus to a white passenger as the law of segregation required. She was arrested and, as a result, blacks boycotted buses in Montgomery in 1955 and 1956. Civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr., led the successful boycott; his efforts brought the technique of passive resistance to national prominence. The boycott ended in 1956 with a mandate from the Supreme Court of the United States outlawing all segregated public transportation in the city. The Montgomery boycott was a clear victory for passive resistance, and King emerged as a highly respected leader. Mindful of this, black clergymen from across the South organized the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), with King as its president. The organization was devoted to King's principle, adopted from the nationalist movement in India, that no violence was to be done to opponents of civil rights, even in retaliation or self-defense. In 1963 King led a massive civil rights campaign in Birmingham and organized drives for black voter registration, desegregation, and better education and housing throughout the South. He was arrested during demonstrations in Birmingham and put in solitary confinement for nine days, during which he wrote one of his most famous essays, "Letter from Birmingham Jail." The next month, Birmingham City Commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor ordered fire hoses and police dogs used against civil rights demonstrators, many of them children. A few months later, Ku Klux Klan members planted dynamite in a black Birmingham church, the 16th Street Baptist Church. The explosion killed four young girls. Desegregation of restaurants, one of the goals of the Birmingham demonstrations, was accomplished by the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 that outlawed discrimination in public accommodations. In 1965 King led the Freedom March from Selma to Montgomery to protest restrictions on black voters. This demonstration furthered the passage of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965. Widespread registration of black voters under that act led to the election of blacks to a number of local offices and their appointment to many boards and commissions. In 1979 Richard Arrington was elected the first black mayor of Birmingham. Integrated schooling came late to Alabama. Although the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that mandatory segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, Governor George Wallace tried twice in 1963 to prevent integration, first in June at the University of Alabama and then in September at several elementary and secondary schools. Both times, President John F. Kennedy activated the National Guard to facilitate integration. Following the admission of two blacks to the University of Alabama and another to Florence State College in 1963, there was a rapid increase in the number of black students attending formerly all-white Alabama colleges and universities. The increase accelerated after Auburn University and the University of Alabama began recruiting black athletes, first for football and then for basketball scholarships. In 1969 less than 15 percent of the state's black students attended integrated schools. However, by 1970 this had surged to 80 percent. E5 Late 20th Century In 1982 George Wallace was again elected governor, this time by appealing to black voters. In 1986 a controversy within the Democratic nomination process allowed Republican Guy Hunt to become the third Republican governor in Alabama history and the first since Reconstruction. Hunt was reelected in 1990 but was removed from office in 1993 after conviction for misusing state funds for personal expenditures. Hunt fulfilled the terms of his sentence, but was pardoned in March 1998 by the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles. His successor as governor was Democratic Lieutenant Governor Jim Folsom, son of "Big Jim" Folsom. Forrest "Fob" James, who had been elected as a Democratic governor in 1978, ran again and won as a Republican in 1994. Thus, at the end of the 20th century, Alabama had truly become a two-party state. In the 1990s Alabama's economy was sluggish despite investments by manufacturing firms to modernize facilities and equipment. A few industries, such as chemicals and fabricated metals, experienced steady growth because their products were in demand for export. However, textile and clothing companies were struggling, and many factories closed because of foreign competition and slack domestic demand. Alexander City's Russell Mills was the exception. The state government aggressively recruited new industry, citing the state's mild climate, abundant water, numerous deepwater lakes, untapped mineral resources, scenic beauty from mountains to white sand beaches, a willing labor force, and miles of navigable rivers. Alabama was successful in attracting a new Mercedes-Benz automobile assembly plant near Birmingham. Several additional plants associated with the auto industry encouraged an industrial boom in the Birmingham area. At the end of the century Alabama faced many of the problems that plagued other areas, including widespread poverty, rising crime rates, and unemployment. The state also had an old (1901) and obsolete constitution, an inadequate tax structure, and problems in education and health care. In 1998 Don Siegelman, a Democrat, was elected governor on the single-issue platform of a state lottery to fund educational reforms. In the following year, however, voters rejected the state referendum that would have established the lottery after religious leaders across the state campaigned against it. F The 21st Century In the early 21st century Alabama, like many states, faced a budget crisis as the economy slowed. In 2002 Republican Bob Riley defeated Siegelman in a close race for governor. Riley pledged to appoint a commission to study reforming Alabama's constitution, and to improve the state economy. The history section of this article was contributed by Leah Marie Rawls Atkins. Contributed By: Leah Marie Rawls Atkins Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.