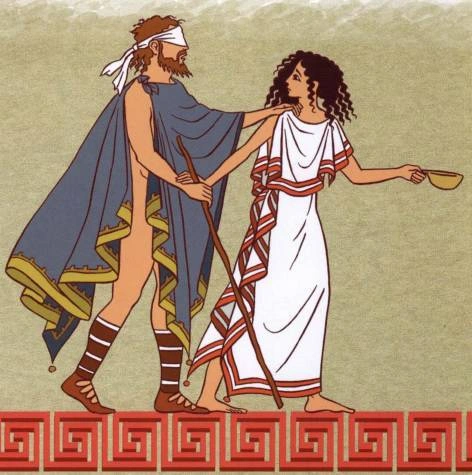

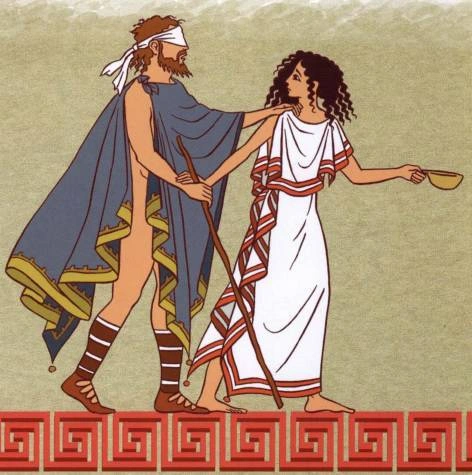

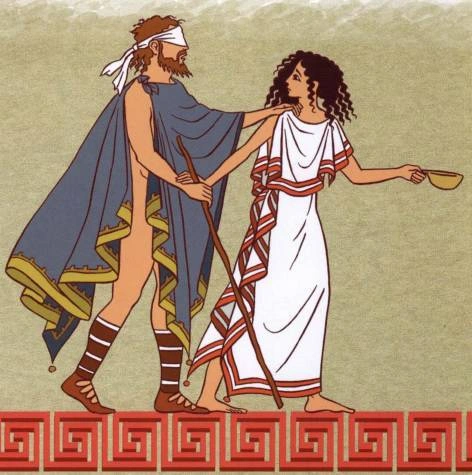

From Bulfinch's Mythology: Antigone - anthology. The classical Greek legend of Antigone, daughter of Oedipus, king of Thebes, exemplified how fate can overshadow a person's life. After Antigone's grandfather Laius, king of Thebes, was warned by an oracle that his son would kill him, he left his infant son Oedipus to die on a mountain, an act which set into motion the defining events of Antigone's life. In this 19th-century interpretation, American mythologist and writer Thomas Bulfinch related the story of Antigone's devotion to her brother Polynices, who was killed in a battle for Oedipus's throne. Antigone risked her life by burying Polynices after the new king declared him a traitor and refused to bury him. From Bulfinch's Mythology: Antigone By Thomas Bulfinch A large proportion both of the interesting persons and of the exalted acts of legendary Greece belongs to the female sex. Antigone was as bright an example of filial and sisterly fidelity as was Alcestis of connubial devotion. She was the daughter of OEdipus and Jocasta, who with all their descendants were the victims of an unrelenting fate, dooming them to destruction. OEdipus in his madness had torn out his eyes, and was driven forth from his kingdom Thebes, dreaded and abandoned by all men, as an object of divine vengeance. Antigone, his daughter, alone shared his wanderings and remained with him till he died, and then returned to Thebes. Her brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, had agreed to share the kingdom between them, and reign alternately year by year. The first year fell to the lot of Eteocles, who, when his time expired, refused to surrender the kingdom to his brother. Polynices fled to Adrastus, king of Argos, who gave him his daughter in marriage, and aided him with an army to enforce his claim to the kingdom. This led to the celebrated expedition of the 'Seven against Thebes,' which furnished ample materials for the epic and tragic poets of Greece. Amphiaraus, the brother-in-law of Adrastus, opposed the enterprise, for he was a soothsayer, and knew by his art that no one of the leaders except Adrastus would live to return. But Amphiaraus, on his marriage to Eriphyle, the king's sister, had agreed that whenever he and Adrastus should differ in opinion, the decision should be left to Eriphyle. Polynices, knowing this, gave Eriphyle the collar of Harmonia [daughter of the god of war and the goddess of love], and thereby gained her to his interest. This collar or necklace was a present which Vulcan [the god of fire] had given to Harmonia on her marriage with Cadmus [founder and first king of the city of Thebes], and Polynices had taken it with him on his flight from Thebes. Eriphyle could not resist so tempting a bribe, and by her decision the war was resolved on, and Amphiaraus went to his certain fate. He bore his part bravely in the contest, but could not avert his destiny. Pursued by the enemy, he fled along the river, when a thunderbolt launched by Jupiter opened the ground, and he, his chariot, and his charioteer were swallowed up. It would not be in place here to detail all the acts of heroism or atrocity which marked the contest; but we must not omit to record the fidelity of Evadne as an offset to the weakness of Eriphyle. Capaneus, the husband of Evadne, in the ardour of the fight declared that he would force his way into the city in spite of Jove himself. Placing a ladder against the wall he mounted, but Jupiter, offended at his impious language, struck him with a thunderbolt. When his obsequies were celebrated, Evadne cast herself on his funeral pile and perished. Early in the contest Eteocles consulted the soothsayer Tiresias as to the issue. Tiresias in his youth had by chance seen Minerva bathing. The goddess in her wrath deprived him of his sight, but afterwards relenting gave him in compensation the knowledge of future events. When consulted by Eteocles, he declared that victory should fall to Thebes if Menoeceus, the son of Creon, gave himself a voluntary victim. The heroic youth, learning the response, threw away his life in the first encounter. The siege continued long, with various success. At length both hosts agreed that the brothers should decide their quarrel by single combat. They fought and fell by each other's hands. The armies then renewed the fight, and at last the invaders were forced to yield, and fled, leaving their dead unburied. Creon, the uncle of the fallen princes, now become king, caused Eteocles to be buried with distinguished honour, but suffered the body of Polynices to lie where it fell, forbidding every one on pain of death to give it burial. Antigone, the sister of Polynices, heard with indignation the revolting edict which consigned her brother's body to the dogs and vultures, depriving it of those rites which were considered essential to the repose of the dead. Unmoved by the dissuading counsel of an affectionate but timid sister, and unable to procure assistance, she determined to brave the hazard, and to bury the body with her own hands. She was detected in the act, and Creon gave orders that she should be buried alive, as having deliberately set at naught the solemn edict of the city. Her lover, Hæmon, the son of Creon, unable to avert her fate, would not survive her, and fell by his own hand.... The following is the lamentation of Antigone over OEdipus, when death has at last relieved him from his sufferings: 'Alas! I only wished I might have died With my poor father; wherefore should I ask For longer life? O, I was fond of misery with him; E'en what was most unlovely grew beloved When he was with me. O my dearest father, Beneath the earth now in deep darkness hid, Worn as thou wert with age, to me thou still Wast dear, and shalt be ever.' Francklin's Sophocles. Source: Bulfinch, Thomas. Bulfinch's Mythology: The Age of Fable, The Age of Chivalry, Legends of Charlemagne. New York: Random House, 1934.