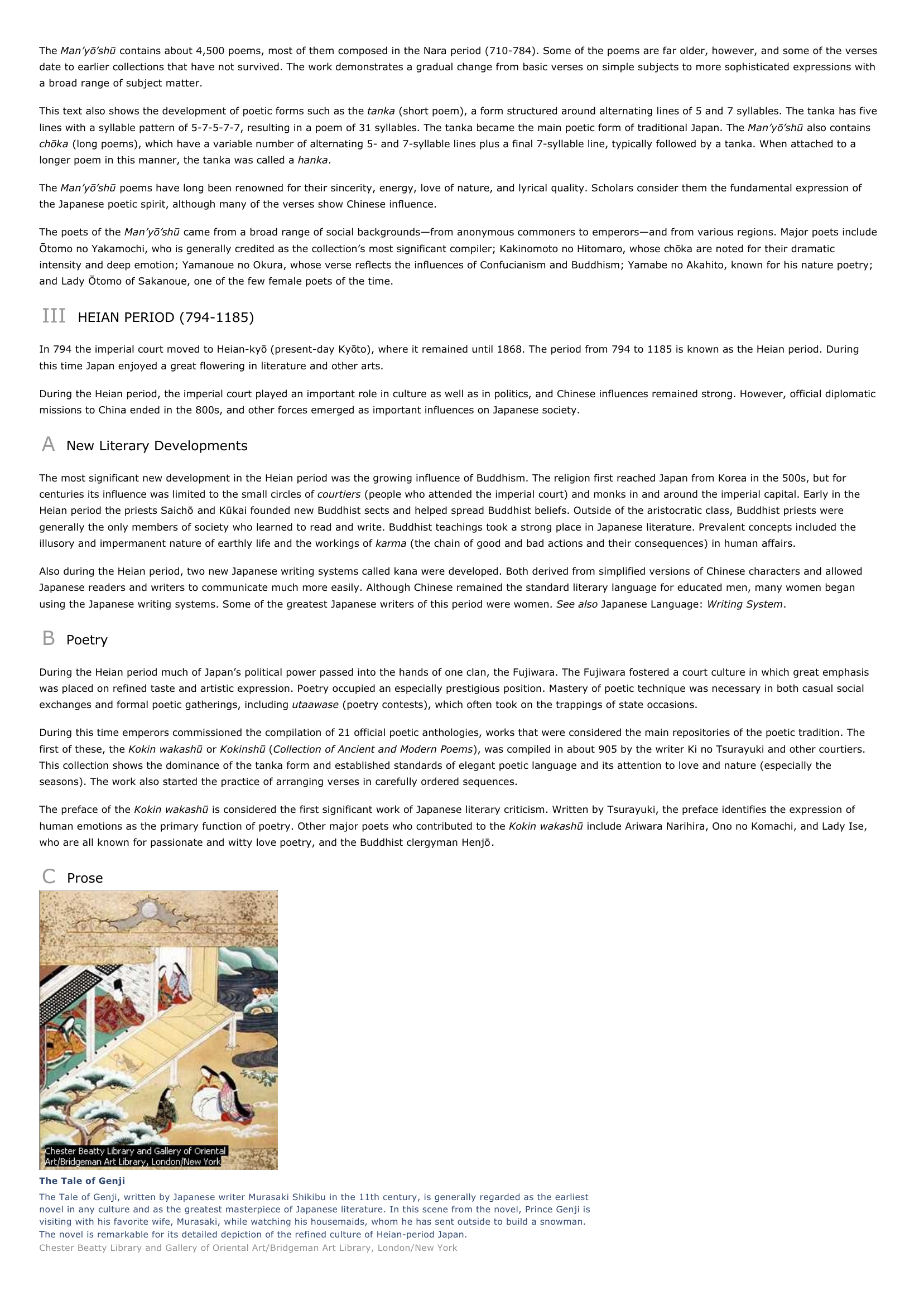

Japanese Literature I INTRODUCTION Japanese Literature, literature of Japan, in written form from at least the 8th century AD to the present. Japanese literature is one of the oldest and richest national literatures. Since the late 1800s, Japanese writings have become increasingly familiar abroad. Genres such as haiku verse, n? drama, and the Japanese novel have had a substantial impact on literature in many parts of the world. The literary history of Japan, like the history of the country itself, has been marked by alternating periods of isolation from the outside world and engagement with it. During times of greater contact with foreign societies, Japanese literature absorbed new approaches, genres, and concepts. Another consistent factor in Japanese literature over the centuries has been a tension between the generally traditionalist values of the elite members of society and the innovative impulses that have come from the culture of common people. Both camps influenced each other, and both contributed greatly to Japanese literary history. Other distinctive qualities of Japanese literature include sensitivity to the place of nature in human life, an emphasis on sincerity of expression, and the uncommon prominence of female writers, as compared with the literary histories of most cultures. Scholars customarily divide the general history of Japan into periods based on shifts in the location of the national capital and changes in governmental institutions, such as the Heian period (794-1185), the Muromachi period (1333-1603), and the Tokugawa period (1603-1868). The literary history of Japan can be broken down according to these same periods. The major dividing line between the traditional and modern periods of the country is conventionally set at the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which also signaled a new era of modernization and contact with the West. II EARLY JAPANESE LITERATURE (ANCIENT TIMES TO LATE 700S) The earliest period of Japanese literature saw the gradual emergence of a body of written materials based on native songs, myths, legends, and prayers. Some of these works were preserved in later collections, but often only in partial or revised form. By the end of this phase a literature of substantial variety and sophistication had come into being. Beginning in the AD 300s, rulers in the Yamato region of Japan, on the island of Honsh? , began consolidating their holdings into a unified, centralized state under the rule of an imperial court. The imperial court occupied a succession of capitals, including one in Heij?-ky? (the modern city of Nara) from 710 to 784. The imperial court was home to a small literate class consisting of Chinese and Korean immigrants and some native Japanese court officials. The earliest literary texts were produced by these people. During this early period, Chinese culture influenced virtually all aspects of court culture, including literature. For example, Chinese script was introduced in the 5th century and became the first writing system used in Japan. This practice continued for more than 1,000 years, even after a useful Japanese writing system was developed. A Histories The earliest works of Japanese literature that have survived intact were sponsored by the imperial court in the 700s. Kojiki (712; Records of Ancient Matters) is a chronicle apparently compiled by a court scribe based on oral traditions and possibly also from written sources that are now lost. Kojiki contains elements of myth (including the creation of the world and the Japanese islands), legend, and history. It also features family histories, poems, and religious incantations. Covering the time from antiquity to 628, Kojiki attempts to establish the divine ancestry of the imperial dynasty and to legitimize its position as the ruling house of Japan. The work uses Chinese characters in two different ways: to convey meanings as in the Chinese language and to represent different sounds that, when put together, approximate spoken Japanese words. Another chronicle, Nihon shoki (720; Chronicles of Japan), covers much the same subject matter as Kojiki but extends the history to 697. Nihon shoki was the first of a series of six imperial histories known as Rikkokushi (Six National Histories). All were modeled on the dynastic histories of imperial China and were written almost entirely in Chinese. B Poetry Go-Toba This illustration depicts Japanese emperor Go-Toba working at an anvil after his exile in 1221. Go-Toba was a poet and patron of the arts. Under his direction a collection of Japanese poetry known as the Shinkokinshu was compiled Private Collection/Laurie Platt Winfrey, Inc. The earliest collection of Japanese poetry, the Man'y?'sh? (Collection of 10,000 Leaves), was compiled in the second half of the 700s. Like Kojiki, it was written in a complex adaptation of the Chinese writing system. The Man'y?'sh? contains about 4,500 poems, most of them composed in the Nara period (710-784). Some of the poems are far older, however, and some of the verses date to earlier collections that have not survived. The work demonstrates a gradual change from basic verses on simple subjects to more sophisticated expressions with a broad range of subject matter. This text also shows the development of poetic forms such as the tanka (short poem), a form structured around alternating lines of 5 and 7 syllables. The tanka has five lines with a syllable pattern of 5-7-5-7-7, resulting in a poem of 31 syllables. The tanka became the main poetic form of traditional Japan. The Man'y?'sh? also contains ch?ka (long poems), which have a variable number of alternating 5- and 7-syllable lines plus a final 7-syllable line, typically followed by a tanka. When attached to a longer poem in this manner, the tanka was called a hanka. The Man'y?'sh? poems have long been renowned for their sincerity, energy, love of nature, and lyrical quality. Scholars consider them the fundamental expression of the Japanese poetic spirit, although many of the verses show Chinese influence. The poets of the Man'y?'sh? came from a broad range of social backgrounds--from anonymous commoners to emperors--and from various regions. Major poets include ? tomo no Yakamochi, who is generally credited as the collection's most significant compiler; Kakinomoto no Hitomaro, whose ch?ka are noted for their dramatic intensity and deep emotion; Yamanoue no Okura, whose verse reflects the influences of Confucianism and Buddhism; Yamabe no Akahito, known for his nature poetry; and Lady ? tomo of Sakanoue, one of the few female poets of the time. III HEIAN PERIOD (794-1185) In 794 the imperial court moved to Heian-ky? (present-day Ky?to), where it remained until 1868. The period from 794 to 1185 is known as the Heian period. During this time Japan enjoyed a great flowering in literature and other arts. During the Heian period, the imperial court played an important role in culture as well as in politics, and Chinese influences remained strong. However, official diplomatic missions to China ended in the 800s, and other forces emerged as important influences on Japanese society. A New Literary Developments The most significant new development in the Heian period was the growing influence of Buddhism. The religion first reached Japan from Korea in the 500s, but for centuries its influence was limited to the small circles of courtiers (people who attended the imperial court) and monks in and around the imperial capital. Early in the Heian period the priests Saich? and K? kai founded new Buddhist sects and helped spread Buddhist beliefs. Outside of the aristocratic class, Buddhist priests were generally the only members of society who learned to read and write. Buddhist teachings took a strong place in Japanese literature. Prevalent concepts included the illusory and impermanent nature of earthly life and the workings of karma (the chain of good and bad actions and their consequences) in human affairs. Also during the Heian period, two new Japanese writing systems called kana were developed. Both derived from simplified versions of Chinese characters and allowed Japanese readers and writers to communicate much more easily. Although Chinese remained the standard literary language for educated men, many women began using the Japanese writing systems. Some of the greatest Japanese writers of this period were women. See also Japanese Language: Writing System. B Poetry During the Heian period much of Japan's political power passed into the hands of one clan, the Fujiwara. The Fujiwara fostered a court culture in which great emphasis was placed on refined taste and artistic expression. Poetry occupied an especially prestigious position. Mastery of poetic technique was necessary in both casual social exchanges and formal poetic gatherings, including utaawase (poetry contests), which often took on the trappings of state occasions. During this time emperors commissioned the compilation of 21 official poetic anthologies, works that were considered the main repositories of the poetic tradition. The first of these, the Kokin wakash? or Kokinsh? (Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems), was compiled in about 905 by the writer Ki no Tsurayuki and other courtiers. This collection shows the dominance of the tanka form and established standards of elegant poetic language and its attention to love and nature (especially the seasons). The work also started the practice of arranging verses in carefully ordered sequences. The preface of the Kokin wakash? is considered the first significant work of Japanese literary criticism. Written by Tsurayuki, the preface identifies the expression of human emotions as the primary function of poetry. Other major poets who contributed to the Kokin wakash? include Ariwara Narihira, Ono no Komachi, and Lady Ise, who are all known for passionate and witty love poetry, and the Buddhist clergyman Henj? . C Prose The Tale of Genji The Tale of Genji, written by Japanese writer Murasaki Shikibu in the 11th century, is generally regarded as the earliest novel in any culture and as the greatest masterpiece of Japanese literature. In this scene from the novel, Prince Genji is visiting with his favorite wife, Murasaki, while watching his housemaids, whom he has sent outside to build a snowman. The novel is remarkable for its detailed depiction of the refined culture of Heian-period Japan. Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York During the Heian period, several genres of prose writing emerged and flourished, including diaries; short tales called setsuwa; longer narrative tales; the zuihitsu, nonfiction collections of brief impressions, lists, recollections, and the like; and rekishi monogatari, or historical chronicles. One of the earliest diaries was Tsurayuki's Tosa nikki (935?; Tosa Diary), a partially fictionalized travel account written by a male writer from a woman's point of view. Other well-known diaries from the time include Kager? nikki (974?; The Gossamer Years) by Fujiwara Michitsuna no Haha, Izumi shikibu nikki (1005?; The Diary of Lady Izumi) by Izumi Shikibu, and Sarashina nikki (1060?; Sarashina Diary) by Sugawara Takasue no Musume. These writings, almost all by women, feature descriptions of court life and candid expressions of personal feelings. The setsuwa, or brief fables, were compiled into collections such as Konjaku monogatari (early 1100s; Tales of Times Now Past). This work contains more than 1,100 stories, many of which are of Indian or Chinese origin. The tales that are set in Japan combine folk, historical, and contemporary motifs. Scholars believe that Buddhist priests compiled the Konjaku monogatari and intended some of its stories to be used for religious instruction. Taketori monogatari (950?; Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, 1956) displays folk and supernatural elements similar to those in the setsuwa. Writers familiar with court life produced narrative tales about court society. One such work, Ise monogatari (Tales of Ise, 920?), mixes poetry with brief accounts of courtly love affairs. The most renowned Heian narrative tale is the court romance Genji monogatari (1010?; The Tale of Genji) by Murasaki Shikibu. Many scholars believe this work to be the greatest work of Japanese fiction and the first true novel in any language. A vast narrative encompassing three generations of court life, Genji monogatari tells the story of Prince Genji, who represents the courtly ideals of physical beauty, artistic refinement, and social sophistication. Much of the tale's interest derives from the sensitively depicted female characters. Their love affairs with Genji and other courtiers provide the main strands of the story line. The turbulent political currents of court life and the Buddhist doctrines of impermanence and karma are also significant elements. A major author in the zuihitsu genre was Sei Sh?nagon, whose masterpiece is Makura no s? shi (1000?; The Pillow Book). This work contains hundreds of brief but strikingly expressed observations, reflections, and lists of items under headings such as "beautiful things," "splendid things," "embarrassing things," "birds," and "winds." These pieces reflect the author's lively intelligence and love of elegance. The rekishi monogatari tell of major events and personalities at court. Some of them include legendary or imaginary episodes. The best-known examples of this genre are Eiga monogatari (11th century; A Tale of Flowering Fortunes) and ? kagami (1120?; The Great Mirror). IV KAMAKURA PERIOD (1185-1333) A gradual weakening of the authority of the Heian court led to a period of increasingly widespread turmoil and a shift of power from the court aristocracy to a class of warriors based in the provinces. These warriors were known as samurai. By 1185 a shogun (military commander) named Minamoto no Yoritomo had established a military government in Kamakura, far from the imperial capital in Ky?to. The Kamakura shogunate assumed military control of the country, although the imperial court retained much of its prestige. This new style of military government was called a bakufu, often referred to in English as a shogunate. A shogun ruled through a network of personal vassals (gokenin) who pledged loyalty to him. Buddhism remained a major influence, and it developed in new directions. The years of turmoil around 1185, when the Heian order fell, inspired a widespread belief that the world had entered a degenerate stage in which Buddhist teachings were losing their force. But then Pure Land Buddhism became popular. This sect preached a doctrine of reliance on the Buddha Amida for salvation. According to this doctrine, all those who call on Amida will be reborn in his Pure Land. The doctrine opened Buddhism to the masses of the common people. A Poetry Tanka poetry, the 31-syllable, 5-line form developed very early in the Japanese literary tradition, experienced a new burst of energy and creativity during the Kamakura period. The leading poet of the late 1100s, Fujiwara Toshinari, also called Shunzei, depicted natural scenes with symbolic overtones. He also spoke for the influential ideals of y? gen (mystery and depth) and sabi (evocation of the beauty of austere, even desolate landscapes). Shunzei's poetics were maintained and developed by his son Fujiwara Sadaie, also called Teika. Teika is credited with being the compiler of the Ogura hyakunin isshu (1235?; Single Poems by 100 Poets), the best-known of all tanka collections. He was also one of the principal compilers of the Shinkokinsh? (1205?; New Collection of Ancient and Modern Times), the eighth imperial anthology. This work, along with the Man'y?sh? and the Kokinsh?, ranks among the most influential collections of Japanese poetry. Like other imperial anthologies, Shin Kokinsh? contains both contemporary and older poems and strongly reflects the taste of its compilers and their society. Major poets represented besides Shunzei and Teika include Princess Shokushi and the Buddhist priests Saigy? and Jien. The dominant tone of the work, reflecting the doctrines of Buddhism and, perhaps, the weakening of the imperial court, is contemplative, marked by a sense of the instability of life and the inevitability of loss. As if to preserve the authority of the court aristocracy, tanka poets from this point became increasingly conservative, even formulaic. They emphasized strict transmission of carefully preserved traditions. B Other Genres Other earlier forms survived into the new era, including setsuwa collections such as Uji sh?i monogatari (early 1200s; A Collection of Tales from Uji) and diaries by court ladies such as Izayoi nikki (1280; The Diary of the Waning Moon), by the nun Abutsu, and Towazugatari (1307?; The Confessions of Lady Nij?) by Gofukakusa In Nij?. Two of the greatest zuihitsu works also date from this age. H?j ?ki (1212; An Account of My Hut) by Kamo no Ch?mei recounts in striking language the destruction caused by natural disasters, social and political upheavals, and warfare in the late 1100s. In the work, the author meditates on the inevitability of suffering and impermanence and describes his attempt to transcend them by living a life of elegant simplicity as a Buddhist recluse. During another period of turmoil at the end of the Kamakura shogunate, Yoshida Kenk?, who like Ch?mei achieved prominence as a court poet only to turn to a secluded life as a Buddhist monk, produced his Tsurezuregusa (1330?; Essays in Idleness). Its 243 brief sections contain observations, recollections, and commentaries on a wide range of topics. Somewhat self-contradictory at times, the commentaries' inconsistency reflects the author's appreciation of the beauty of the irregular, the incomplete, and the transitory and his acceptance of imperfection in human life. The book has long been one of the most frequently cited expressions of distinctively Japanese aesthetic, social, and spiritual values. Perhaps the most distinctive literary development in the warrior-dominated Kamakura period was the composition and dissemination of numerous gunki monogatari, or war tales. These stories detail the exploits and values of the samurai. The most renowned tale is Heike monogatari (begun 1220?; Tale of the Heike), a lengthy account of the defeat of the Taira clan by the rival Minamoto clan at the close of the Heian period. The tale was composed gradually and spread throughout Japan by luteplaying reciters called biwa h?shi. It eventually made it into written form. Heike monogatari combines elements of historical chronicle, epic ballad, dramatic tragedy, and Buddhist sermon in a richly poetic language. Many of its episodes and phrases provided a basis for later works. V MUROMACHI PERIOD (1333-1603) The Mongol Empire attacked Japan in 1274 and again in 1282. Weakened by these attacks and by internal dissension, the Kamakura shogunate collapsed in 1333. It was replaced by a new shogunate founded by the warrior Ashikaga Takauji; this new shogunate was based in the Muromachi district of Ky? to. The resulting close contact between warriors and the court aristocrats helped shape cultural developments in this era. Another trend was the creation of new literary forms that combined elements from the high culture of aristocrats and samurai and the culture of the lower classes. A N? Drama New tendencies were most apparent in the evolution of the n? drama, which developed under the patronage (monetary and political support) of the Ashikaga shoguns and other samurai and through the guidance of playwright and performer Kan'ami Kiyotsugu and his son Zeami Motokiyo. The n? drama was molded into a profound dramatic art from a variety of relatively simple popular song, dance, and mime entertainments. N? drama drew its settings, characters, and language from the classic traditions of tanka and court monogatari such as Ise monogatari, Genji monogatari, and Heike monogatari. Zeami's many critical treatises include F?shi Kaden (1400-1402; Teachings in Acting Style and the Flower) and Shikad? (1420; The True Path to the Flower). These works raised the artistic level of n? by stressing the concepts of hana, the effect of extraordinary beauty conveyed to the audience through the actor's performance, and yugen, grace and elegance in speech, movement, and music. A similar process of refinement took place in kyogen, the comic interludes performed as companion pieces to n? . In kyogen, nonheroic characters, mainly of lower social rank, appear in everyday situations. See Japanese Drama: N? Drama. B Renga Renga (linked verse) was an offshoot of tanka that had been practiced for generations as an informal amusement. To create a renga, one poet would introduce a threeline opening and another poet would add a two-line continuation. Still another poet could then add a new three-line phrase that linked to the themes previously introduced, followed by a two-line verse, and the cycle would continue. Renga produced for ceremonial occasions could be as long as 10,000 lines. Renga flourished in the 1400s, when it emerged as a major verse form with its own sophisticated aesthetics and patronage. Gifted poets included the Buddhist priests Sh?tetsu, Shinkei, and S?gi. Court poet Yoshimoto Nij? compiled the first important renga anthology, Tsukubash? (1356-1357; Tsukuba Collection). S?gi was a cocompiler of the Shinsen Tsukubash? (1495; New Tsukuba Collection) and was one of the participants in the Minase sangin hyakuin (1488; A Hundred Stanzas by Three Poets at Minase), a 100-verse sequence that is considered the major renga masterpiece. Unlike the earlier tanka poets, many leading renga poets were of humble birth, and they were able (and sometimes forced) to associate freely with commoners as well as nobles and samurai in their artistic pursuits. C Military Tales The continuing popularity of military tales in the Muromachi period reflected the dominance of the samurai and the continuation of warfare and unrest. Most of these tales were written by multiple anonymous contributors over a period of years. Taiheiki (1372?; Chronicle of the Great Peace) recounts the conflicts from 1318 to 1367 in a style that combines elements of the earlier historical chronicles and the war tales (gunki monogatari) developed in the Kamakura period. Gikeiki (1400?; The Story of Yoshitsune), like many popular Japanese narratives, tells of the exploits and downfall of a semilegendary tragic hero, in this case the dashing Minamoto no Yoshitsune. Soga monogatari (14th century; The Tale of the Soga Brothers) became the basis for countless later retellings of its main theme, a celebrated samurai vendetta. VI TOKUGAWA PERIOD (1603-1868) During the second half of the Muromachi period, the authority of the shogunate lessened and local warlords vied for power. These developments resulted in almost continual warfare and conditions of near-anarchy. The arrival of Portuguese traders and missionaries, starting about 1543, also unsettled the political situation. Soon other Europeans arrived, bringing Christianity and new technology such as firearms. In the late 1500s a succession of three warlords--Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu--restored Japan's national unity and order. The Tokugawa shogunate that Ieyasu established in 1603 with headquarters in Edo (present-day Tokyo) lasted more than 250 years and brought a period of unprecedented peace and stability. The shogunate ruled strictly to maintain national security and its own power. Rulers prohibited most contact with other societies, and they promoted the division of society into a rigid hierarchy composed of four hereditary classes: a ruling elite of warriors (the samurai) and the commoner classes of peasants, artisans, and merchants. Although the merchant class was the lowest in social rank, many merchants accumulated substantial wealth as commerce flourished with the return of order and stability. By the late 1600s a new urban-based culture was on the rise. A Genroku Period The first great flowering of this new culture occurred during the early Tokugawa period, known as the Genroku period, from 1688 to 1704. During this time, more and more Japanese learned to read and the growth of mass-production printing helped increase access to and familiarity with literary texts. One of the most significant new literary forms was haikai, a variety of linked verse that developed as an offshoot of the renga form. Early haikai were largely undistinguished, but the poet Bash? elevated the form to its highest level by endowing it with unprecedented refinement and spiritual depth. Particularly eloquent were his hokku, 17-syllable stanzas of three lines (in a 5-7-5 syllable pattern) that began the haikai sequences. This form, which combined observations about nature and humans with profound spirituality, later became known as haiku. Bash? is also renowned for his travel accounts. In his Oku no hosomichi (1702; The Narrow Road to the Deep North), haiku verses accompany lyrical prose descriptions of his visits to scenic, historical, and literary sites in northern Japan. Other well-known poets of haikai and haiku include Buson, a painter-poet with an elegant pictorial style, and Issa, noted for his humanism and his witty, sympathetic verses about small animals. Much of the new urban culture centered on the licensed pleasure quarters of the major cities. These areas featured brothels, theaters, and eating and drinking places that provided diversion and release from the rigid restrictions of ordinary life. They also became lively centers of art and fashion. The zesty spirit of this ukiyo, or floating world, was captured in writings known as ukiyo-z?shi (tales of the floating world). The best-known writer of this genre was Ihara Saikaku, who employed a lively prose style and celebrated the delights and uncertainties of a life devoted to indulgence in passion. His works include K?shoku ichidai otoko (1682; The Life of an Amorous Man), K?shoku ichidai onna (1686; The Life of an Amorous Woman), and K?shoku gonin onna (1686; Five Women Who Loved Love). Saikaku's later tales portray the more sober virtues of diligence, thrift, and honor. His acute observations of human nature earned him a reputation as the founder of Japanese realism. Another major figure of the time was dramatist Chikamatsu Monzaemon, who wrote for kabuki theater and j? ruri puppet theater (also called bunraku). Kabuki theater features music, dancing, and brilliantly colored, elaborate sets. In puppet theater, the puppets are manipulated and accompanied by chanting and music. See Japanese Drama: Puppet and Kabuki Theater. Chikamatsu's colorful, violent depictions of historical and legendary warrior heroes were wildly popular, but his most lasting achievements were domestic dramas based on actual incidents. These dramas feature characters from humble merchant-class backgrounds in ? saka. In the most famous of these, Sonezaki shinj? (1703; The Love Suicides at Sonezaki) and Shinj? ten no amijima (1720; The Love Suicides at Amijima), Chikamatsu uses richly poetic language to portray a young merchant and his courtesan lover who find themselves caught between the immovable moral obligations of society (giri) and the irresistible force of human emotions (ninj?). The only escape is a lovers' suicide that shows commoners willingly engaging in a kind of heroic self-sacrifice that was previously considered exclusive to the samurai class. B Late Tokugawa Period In the latter half of the Tokugawa period, the center of cultural activity shifted eastward from Ky?to and ? saka to Edo, the seat of the shogunal government. During this time, many major works were produced and new genres were developed. The volume and variety of literary activity expanded and commercial publishing increased. For the first time, writers with popular appeal could make a living from their work. Also, professional publishers of popular literature, such as Hachimonji-ya in Ky? to, became commercially viable. Kabuki drama continued to be popular, while j? ruri gradually declined. Haikai poetry also remained popular, and there were elaborate networks of professional masters, competitions, and schools devoted to it. The form also gave birth to several variant forms of casual, light verse collectively known as zappai. The most successful form was senry?, sharply satirical poems in a 17-syllable haiku format that are still composed by modern poets. During the late Tokugawa period there was a rise in the publication of fiction tales that appealed to a broad and relatively unsophisticated audience. These works frequently recycled material from existing sources, including folk tales, legends, histories, Chinese novels, and kabuki plots. These diverse strains are integrated most skillfully in the work of Ueda Akinari, especially in the intricate language and psychological penetration of his Ugetsu monogatari (1768; Tales of Rain and Moonlight). Highly sophisticated fictions were composed in the late 1700s and early 1800s by educated samurai and merchants, many of them men of ability but low social rank. Denied outlets for their ambitions in a rigid social structure, they turned to literature and art to exercise their talents. Many wrote ky? ka (comic verses in tanka form) and gathered at banquets where writers from diverse social backgrounds could enjoy the rare opportunity to mingle freely. The gesaku (playful prose compositions) produced during this time ranged from satires and freewheeling fantasies by Hiraga Gennai to witty accounts of pleasurequarter connoisseurs by Sant? Ky? den to worldly character studies by Shikitei Samba. Picaresque comedies by Jippensha Ikku and elaborate historical narratives by Takizawa Bakin appealed to broad popular audiences. VII MODERN PERIOD (1868-PRESENT) In the mid-1800s the political institutions of the Tokugawa shogunate weakened. This process accelerated markedly after 1853, when an American naval expedition appeared in Japanese waters and demanded an end to the policy of diplomatic and commercial seclusion that Japan had followed for more than 200 years. Facing the Westerners' military and technological superiority, the shogunate could not resist these demands. However, the signing of several treaties with Western countries in the 1850s undermined the shogunate's authority and intensified the long-developing discontent with the rule of the shoguns among proimperial nationalists. In 1868 a coalition of proimperial samurai in western Japan overthrew the Tokugawa shogunate, ushering in the modern phase of Japanese history. Meiji Restoration. A Meiji Period (1868-1912) The emperor Meiji ascended to the throne just as these political changes were occurring. At the same time, Japan's imperial capital moved from Ky?to to the former shogunal capital of Edo, which was renamed Tokyo. During the emperor's reign, known as the Meiji period (1868-1912), Japan developed modern political, military, economic, and social institutions. The Meiji years also brought advances in education, science and technology, commerce, and industry. In the early years of the Meiji period, Japanese intellectuals grappled with the challenges of adopting new political and social values while the people struggled to understand the scientific, technological, and economic systems of the West. Influential proponents of Western-style development in Japan were indifferent or even hostile to literature, viewing it as a diversion from urgent practical concerns. In the 1880s, however, a new literature began to take shape. Its authors came from among the small group of young people educated in the newly created Westernstyle universities and familiar with the literatures of European countries. A1 Fiction The novel, long considered one of the less prestigious forms in Japan, gradually rose after 1868 to the central literary position that it occupied in the West. This rise was fueled by a growing stream of Japanese translations of European fiction beginning in the 1870s, as well as by a number of political allegories in novel form that were produced by Japanese authors in the 1880s. Another important push came from the publication of Tsubouchi Sh?y? 's critical treatise Sh?setsu shinzui (1885-1886; The Essence of the Novel). In 1887 Futabatei Shimei began publication of Ukigumo (1887-1889; Drifting Cloud, 1967), which has been widely hailed as the first successful modern Japanese novel. Futabatei's work features a realistic portrayal of the tensions and inconsistencies of society in the Meiji years, an acute representation of his characters' interior lives, and a new style of narrative language based on modern speech. From the 1880s until the early 1920s, new techniques and approaches--many of them rooted in Western traditions--continued to be a major feature of the Japanese literary scene. At the same time, many traditional literary features proved remarkably resilient. Sometimes they were employed as a form of resistance to the forces of innovation, but often they worked with them in a fruitful synthesis. A1a Mori ?gai and Natsume S?seki Natsume Soseki Japanese author Natsume Soseki first gained public attention with his Wagahai wa neko de aru (1906; I Am a Cat, 1961), a generally light-hearted series of observations that a cat makes about humans. Soseki later published more serious psychological novels. Japan Museum of Modern Literature The two most renowned fiction writers of the Meiji period were Mori ? gai and Natsume S?seki. Both authors studied abroad in their youth--?gai in Germany and S?seki in England--and both became well versed in Western literary developments. ? gai, who had a distinguished career as an army medical officer, was a versatile writer who produced important works in a wide range of genres, including fiction, drama, poetry, and criticism. His early writing was heavily influenced by European-style romanticism, and he explored the shape and limitations of Japanese efforts to adapt to Western ways in works such as Maihime (1890; The Dancing Girl, 1975) and Fushinch? (1910; Under Reconstruction, 1962). Later he turned his attention to materials and themes drawn from Japanese history, especially the austere values of the samurai class, in a series of works that includes Abe ichizoku (1913; The Abe Family, 1977) and Shibue ch? sai (1916; Woman in the Crested Kimono, 1985). Readers admired ? gai for his clear, dignified style, which served as a model for many later writers. His work as a translator and editor introduced new ideas and forms and helped launch the careers of younger writers. S?seki began his career as a scholar of English literature. His lighthearted, satirical early novels Wagahai wa neko de aru (1906; I Am a Cat, 1961) and Botchan (1906; translated 1972) were immediately successful and remain popular. However, his reputation is based largely on a series of finely wrought psychological novels such as Mon (1910; The Gate, 1972) and Kokoro (1914; translated 1957) that probe the interior lives of insecure, lonely characters struggling to find meaning in the modern world. A1b Naturalist School A major development late in the Meiji period was the emergence of the influential naturalist school. The Japanese naturalists drew their original inspiration from the naturalism that emerged in Europe in the late 19th century. European naturalist writers aimed at an objective depiction of life. They believed that human behavior was determined by hereditary instincts and emotions and by the social and economic environment, rather than by free human choice. At first, with the publication of the novel Hakai (1906; The Broken Commandment, 1974) by Shimazaki T? son, Japanese naturalism seemed poised to take a similar course. The book created a sensation with its frank portrayal of a member of Japan's burakumin (outcast) class and his struggles against social forces beyond his control. However, the publication of Tayama Katai's Futon (1907; The Quilt, 1981) changed the course of naturalism. An account of a middle-aged married writer's hopeless infatuation with a young woman, the book was widely assumed to be based on events in Katai's own life. Although it was not the first example of autobiographical fiction in modern Japan, the boldness of Katai's confession created a powerful impression of honesty and sincerity. Revelations of the excesses and frustrations of struggling young writers--thinly fictionalized and heavy on sordid details and gloomy atmosphere--quickly replaced social issues as the primary subject matter of Japanese naturalism, which established itself as the dominant form of Japanese fiction. A1c Reaction Against Naturalism Tanizaki Jun'ichir? Many of the works of Japanese author Tanizaki Jun'ichir? focus on male-female relationships. He is best known for Tade kuu mushi (1929; Some Prefer Nettles, 1955), about a failing marriage. The Mainichi Newspaper Co., Ltd. Despite the popularity of naturalism, writers such as S?seki, ? gai, Nagai Kaf? , and Tanizaki Jun'ichir? offered alternatives. These writers valued beauty and imagination over confessional realism, and their work ultimately proved to have more staying power than that of the naturalists. Important works included Nagai's Sumidagawa (1909; The River Sumida, 1965) and Bokut? kidan (1937; A Strange Tale from East of the River, 1965) and Tanizaki's Sasameyuki (1943-1948; The Makioka Sisters, 1957). A2 Poetry and Drama Poetry and drama were also caught up in the Meiji tide of modernization, and youthful reformers gave traditional poetic forms new vitality. These writers included Ochiai Naobumi and Yosano Tekkan, who adapted the ancient tanka form by reviving long-dormant themes and styles and introducing new ones. Yosano's wife, Akiko, scandalized conservatives with her outspoken individualism and sensuality, but her collection Midaregami (1901; Tangled Hair, 1971) established her as one of the greatest poets of the age. Ishikawa Takuboku's tanka, with their direct but eloquent style and evocations of the loneliness of modern life, have remained favorites. Masaoka Shiki campaigned to return freshness to the haiku form by advocating the principle of shasei, or composition based on direct observation. Translations of contemporary European poetry by ?gai and others led to attempts at shintaishi (new-style poetry) outside the traditional forms. The first of these to make a strong impression on readers was the romantic collection Wakanash? (Collection of Young Herbs, 1897) by Shimazaki. Kabuki theater maintained its popularity during the Meiji period, but new styles of drama also emerged. Shinpa was a kabuki offshoot that brought contemporary themes, adaptations of well-known novels, and foreign plays to the stage. Beginning in the final years of the Meiji period, shingeki (new theater) emerged, modeled on Western theater. For example, Tsubouchi Sh?y ?, one of the originators of shingeki, is well known for his Japanese translations of the complete works of William Shakespeare. See Japanese Drama. B Era of the World Wars (1912-1945) The death of the Meiji emperor in 1912 marked the close of Japan's initial period of modernization. The reign of his son Yoshihito, which lasted until 1926, is known as the Taish? period. Major events during this period included the expansion of the industrial economy and the gradual emergence of democratic political institutions. B1 Taish? Period Naturalism lost some of its momentum during the Taish? years. Instead, a thinly fictionalized autobiography form called shish?setsu dominated the fictional landscape. This type of work was a distinctive combination of modern-style realistic elements and traditional aesthetic and psychological patterns. The writers of the Shirakaba (white birch) school rejected the gloom and claustrophobia of naturalist fiction and offered an idealistic, humanistic optimism that won great popularity. The most celebrated of the Shirakaba writers, Shiga Naoya, was noted for the sensitivity of his observations and the spare purity of his style. Numerous other writers, such as Kasai Zenz? and Uno K?ji, were not closely connected with any school but rose to prominence with autobiographical works. Another major Taish? figure, Akutagawa Ry? nosuke, initially won acclaim for short stories such as "Rash?mon" (1915; "Rashomon," 1930), which later became the basis for a famous Japanese motion picture, and "Hana" (1916; "The Nose," 1930). Akutagawa added a modern psychological element to these reworkings of traditional tales. Later he turned to satirical fantasy in Kappa (1927; translated 1947) and to a series of harrowing self-portraits of a spirit on the verge of collapse, including Haguruma (1927; Cogwheels, 1965). Akutagawa's suicide in 1927 was the first in a series of suicides over the next few decades by first-rank Japanese writers. Among the theories for this pattern of suicides are the crisis of coping with modernity, the predicament of artists unable to find a secure position in the modern world of Japan, and the Japanese tradition that looks upon suicide as an acceptable--and sometimes even necessary--way out of a difficult conflict or dilemma. In poetry, the most striking development during the Taish? years was the emergence of Hagiwara Sakutar? , who wrote eerie and compelling symbolist verses. Hagiwara's writings were the first successful Japanese poetry to use modern everyday language rather than the classical style of traditional poetic idiom. B2 Sh?wa Period The Taish? emperor died in 1926 and his son Hirohito became emperor. Hirohito adopted the name Sh?wa (Enlightened Peace) for his reign. During the early years of this period, social tensions gradually increased as Japan felt the effects of the worldwide economic depression and politics took on an increasingly militarist and threatening tone. In literature, several new movements rose rapidly in the late 1920s. The proletarians, a group of writers committed to using their work to advance the revolutionary agenda of Marxism (see Marx, Karl), achieved a brief but spectacular prominence in these years. Although much of their output was later dismissed as heavy-handed propaganda, the proletarians produced some memorable pieces, including Kobayashi Takiji's Kanik?sen (1929; The Cannery Boat, 1933), which centers on the abuses suffered by workers aboard a floating crab cannery. Government repression crushed this movement in the 1930s; Kobayashi died while in police custody in 1933. Other writers insisted just as strongly on the primacy of aesthetic values over political ones. The writers of the shinkankaku-ha, or neo-perceptionist school, were inspired by recent European developments such as surrealism and stream-of-consciousness narrative techniques. They sought to launch their own kind of literary revolution by incorporating experimental modes of expression into their work. Although the shinkankaku-ha movement proved to be short-lived, a few of its adherents, most notably Kawabata Yasunari and Yokomitsu Riichi, made major contributions to Japanese fiction with works that featured strikingly unorthodox expression and psychological exploration. Among the best examples of this tendency is Kawabata's Yukiguni (1948; Snow Country, 1956), which tells the story of an ill-fated love affair between a man and a geisha (female hostess and entertainer) working at a mountain resort. By the late 1920s female fiction writers such as Miyamoto Yuriko, Hirabayashi Taiko, and Sata Ineko had begun attracting attention in increasing numbers. Their work commonly concentrated on the lives of women and their efforts to gain autonomy in a male-dominated world. Autobiographical content and leftist ideological perspectives were major features in many of their works, such as Miyamoto's Futatsu no niwa (Two Gardens, 1947) and Sata's Kurenai (Crimson, 1936). As the unconventional movements faded away by the mid-1930s, established writers such as Shimazaki, Tanizaki, Nagai, Shiga, and the naturalist Tokuda Sh?sei reclaimed the limelight with major new works. At the same time, former Marxists who had renounced their convictions--often while imprisoned--tried to come to terms with their abandonment of Socialist and Communist ideals in a series of works that came to be known collectively as tenk? bungaku (recantation literature). Throughout the 1930s, as Japanese military forces became increasingly embroiled in an invasion of China, most aspects of life moved ever closer to a wartime footing. Works portraying conditions at the front, such as Hino Ashihei's Tsuchi to heitai (Earth and Soldiers, 1938), were wildly popular. After the outbreak of war with the United States and its allies in 1941, government control over cultural activities in Japan was virtually complete. Publication of works deemed unsupportive of the war effort became almost impossible. Many writers participated, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, in government-sponsored literary activities, including trips to report on life in Japan's newly conquered territories. A few authors, such as Nagai, refused to do so and passed the war years in silence. C Post-World War II (1945-1970) Japan's defeat and unconditional surrender in 1945 brought World War II to an end. The ensuing seven years of American occupation brought sweeping changes to virtually all aspects of Japanese life. C1 Aftermath of War Kawabata Yasunari In 1968 Kawabata Yasunari became the first Japanese writer to win the Nobel Prize for literature. His writings balance surface detail and symbolic meaning, and he is known for his use of vivid visual imagery. The Mainichi Newspaper Co., Ltd. In the immediate postwar years, a new personal freedom and the promise of a peaceful, democratic society coexisted with a deep despair caused by wartime devastation, desperate poverty, chronic food shortages, and the disillusionment created by the collapse of the country's political, social, and cultural order. During these years Japan experienced a rush of literary activity, as writers' pent-up energies were suddenly released and readers eagerly sought out new works. Older authors such as Tanizaki, Nagai, Uno, and Shiga were quick to reappear on the scene. Tanizaki's Sasameyuki, the publication of which had been suspended by the government during the war, was finally released in full and was widely hailed as a modern masterpiece. The work is a nostalgic account of changes in the lives of a merchant family in the 1930s. A series of younger writers captured the spirit of the times more accurately by striving to come to terms with the drastically changed social conditions. The novels Shay? (1947; The Setting Sun, 1956) and Ningen shikkaku (1948; No Longer Human, 1958) by Dazai Osamu express the difficulty of enduring in a world where conventional values have become meaningless. Because many of his characters were often overwhelmed by despair and even suicidal, Dazai's suicide in 1948 was widely seen as the expected conclusion to his career and life. Sakaguchi Ango, in a series of stories and essays such as Hakuchi (1946; The Idiot, 1962) and Darakuron (On Decadence, 1946), affirmed the need for spiritual and social regeneration based on human nature rather than on tradition or ideology. Other writers who shared fame with Dazai and Sakaguchi as members of the burai-ha, or outlaw school, include Ishikawa Jun and Oda Sakunosuke. Some authors, especially those who had spent the war years participating in or observing the fighting, examined the meaning of their wartime experiences. ?oka Sh?hei's Nobi (1951; Fires on the Plain, 1957) reveals the depths of physical and spiritual degradation to which the Japanese army was reduced in the war's final stage. Takeyama Michio's Biruma no tategoto (1948; Harp of Burma, 1966) depicts one soldier's pursuit of redemption. In the closing days of World War II, the United States dropped atomic bombs on two Japanese cities, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. More than 100,000 people were killed or missing as a direct result of the bombings, and the attacks prompted many documentary and literary responses. The most celebrated of these is Kuroi ame (1966; Black Rain, 1969) by Ibuse Masuji. Ibuse was not in Hiroshima at the time of the bombing, but he based his novel closely on eyewitness reports and diaries of survivors. Wartime destruction and the dislocations of postwar life play a less direct part in the postwar writing of Kawabata Yasunari. However, in a series of his lyrical novels, including Sembazuru (1952; Thousand Cranes, 1959) and Yama no oto (1954; The Sound of the Mountain, 1970), a war-induced sense of loss forms a backdrop to sensitively rendered characters, lonely individuals who attempt to find some consolation in love, nature, or artistic traditions. In 1968 Kawabata became the first Japanese author to win the Nobel Prize in literature. Depressed and ailing, he committed suicide four years later. Many female writers in Japan tended to depict various aspects of women's lives without addressing explicitly political themes. Hayashi Fumiko, Uno Chiyo, and Enchi Fumiko, who began their careers before the war, became more prominent during the postwar years. Their major successes include Hayashi's Ukigumo (1951; Floating Clouds, 1965) and Enchi's Onnazaka (1949-1957; The Waiting Years, 1971) and Onna men (1958; Masks, 1983). The works of postwar novelists such as Ariyoshi Sawako, K? no Taeko, and Kurahashi Yumiko have continued to center on the contradictions and difficulties of women's lives in modern Japan. C2 New Directions Mishima Yukio The works of Japanese novelist Mishima Yukio were greatly influenced by his distaste for the sterile realities of 20thcentury Japanese society. In his writings and lifestyle, he expressed nostalgia for the stronger values and greater cultural unity of traditional Japanese society. In his ultimate protest against contemporary society, Mishima committed ritual suicide in 1970. UPI/THE BETTMANN ARCHIVE Japan entered a period of recovery and then sustained rapid economic growth after 1950. During this period the sense of urgency that marked the immediate postwar years gradually dissipated. Many writers sought a happy medium between serious and popular literature in the form of ch? kan sh?setsu (in-between fiction), much of which explored social issues such as family life and relations between the sexes. Mass-media culture became an increasingly powerful force, and many writers contributed to the market for entertainment and reportage. Autobiographical fiction continued to have its adherents in the postwar era, but it lost the dominant role that it had enjoyed since early in the century. One of the first writers to emerge as a major presence in the second half of the 20th century was the versatile and prolific Mishima Yukio, whose works depict a modern Japan in which the triumph of materialism and careerism leaves a gaping spiritual void. Mishima was also well known for his outspoken and controversial political views, especially his support for a revival of the authority of the emperor. He even led an unsuccessful military coup d'etat in 1970. Immediately after completing his final work, a series of four novels collectively entitled H?j ? no umi (1969-1971; The Sea of Fertility, 1972-1974), Mishima joined the list of notorious Japanese literary suicides by committing seppuku (self-disembowelment with a sword in samurai fashion). ? e Kenzabur? Japanese novelist ? e Kenzabur? won the 1994 Nobel Prize in literature. His works include Man'en gannen no futtoboru (1967; The Silent Cry, 1974) and Jinsei no shinseki (1989; An Echo of Heaven, 1996). Many of ? e's writings examine alienation in modern Japanese society. Fujifotos/The Image Works Abe K?b? wrote the acclaimed Suna no onna (1962; Woman in the Dunes, 1964) and other novels and plays that mix fantasy with themes of alienation and loss of identity. Another major writer who emerged during this period was ?e Kenzabur?, who created a richly imagined fictional universe that incorporates political and social criticism and deep-seated personal concerns. ? e's novels include Kojinteki na taiken (1964; A Personal Matter, 1968) and Man'en gannen no futtob?ru (1967; The Silent Cry, 1974). In 1994 ?e won the Nobel Prize in literature. Although fiction continued to overshadow poetry and drama in the postwar years, the traditional tanka and haiku forms were still composed in great quantities. Occasionally a distinctive figure, such as female tanka poet Tawara Machi, succeeded in capturing the public imagination. D Contemporary Japanese Literature (1970- ) Haruki Murakami In the late 20th century, Haruki Murakami emerged as one of Japan's leading novelists. Many of his works focus on the challenges that the modern world poses to individuals and society. Mainichi Newspaper Co., Ltd. By the 1970s Japan had developed into an affluent, somewhat complacent society in which literature contended for attention from a public increasingly attuned to massmarket journalism, television, cartoons, movies, and computer games. Under these conditions, writers and readers were generally less inclined to explore social, philosophical, or political issues in a sustained, penetrating way. Writers of this period such as Inoue Hisashi and Tsutsui Yasutaka combined language and conventions from popular culture with imaginative experiments in fictional structure, while still preserving a coherent narrative and moral framework. Inoue's novels include Bun to Fun (1970; Boon and Phoon, 1978), Kirikirijin (The Kirikirians, 1981), and T?ky ? sebun r? zu (Tokyo Seven Rose, 1999). Tsutsui's works include Afurika no bakudan (1968; The African Bomb and Other Stories, 1986) and Kazoku hakkei (1972; What the Maid Saw: Eight Psychic Tales, 1990). Tawara Machi Japanese poet Tawara Machi's first book of tanka poetry, Sarada Kinenbi (1987; Salad Anniversary, 1989), was a huge bestseller. The tanka, a five-line poem containing 31 syllables, is the most popular form of traditional poetry in Japan. Mainichi Newspaper Co., Ltd. Fiction writers born after World War II, such as Haruki Murakami, Tsushima Y? ko, Ry? Murakami, and Banana Yoshimoto, turned away from the modern novel's quest to find meaning in individual lives within a structured society. Instead, they traced the seemingly directionless courses of characters in a world with no center and little past, where the traditional support structures of family, state, and workplace are weakened or absent. Characters in novels such as Haruki Murakami's Sekai no owari to h?doboirudo wand?rando (1985; Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, 1991) and Yoshimoto's Kitchin (1987; Kitchen, 1993) seem as much at home in a world of multinational media culture as in Japan. Murakami's bestseller Noruwei no mori (1987; Norwegian Wood, 1989) takes its title from a popular 1960s song by the rock group the Beatles; the song serves to cue up memories for the novel's main character. Similar references to pop music and other Western cultural elements are prominent in Ry? Murakami's novel 69 (1987; translated 1993). These cross-cultural influences and devices have helped the translated works of these Japanese writers and their contemporaries find an audience in the West. Tsushima, the author of novels such as Yama o hashiru onna (1980; Woman Running in the Mountains, 1991), has been one of Japan's most prominent contemporary female writers since her debut in the late 1960s. Yoshimoto, in her early 20s when she produced Kitchin, is internationally popular and is breaking ground for a new generation of Japanese writers. Modern Japanese literature is being created from a more diverse population than ever, as Japan's Korean and other ethnic communities make their voices heard in Japanese. Some literary scholars have suggested that the Japanese language sometimes seems to be the only distinctively Japanese feature remaining in much of the country's current literature. These changes mirror the evolution of Japanese society as it takes on the challenges of the 21st century. Contributed By: Joel R. Cohn Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.