Cognitive Psychology.

Publié le 10/05/2013

Extrait du document

«

full richness of people’s cognitive experiences.

Describing the act of remembering as a process of storage and retrieval, for example, neglects the subjective experienceof remembering.

Another criticism is that information-processing theory may not reflect how the brain actually works.

Newer models, such as the parallel distributedprocessing model, try to address this criticism by drawing on studies of brain structure and function.

Psychologists continue to debate the adequacy of the information-processing model, but its influence likely will last well into the 21st century.

III METHODS OF RESEARCH

Like other psychologists, cognitive psychologists use a wide variety of research methods.

Methods particularly relevant to cognitive psychology can be organized intothree general categories: (1) self-reports, or people’s descriptions of their experiences; (2) reaction-time measurements; and (3) methods that measure biologicalfactors such as brain activity.

A Self-Reports

One way of researching cognition is to conduct experiments in which the participants are asked to report their experiences.

For example, an experiment on patternrecognition might present people with various visual stimuli and ask them to name what they see.

An experiment on memory ability might require participants to view alist of words, then either say what they can remember (recall) or select the words they saw from a larger list (recognition).

Self-report measures sometimes includepeople’s descriptions of their own intuitions about how their minds work.

For example, people might report on the mental imagery they experience as they listen to astory or to music.

B Reaction-Time Measurements

One common way that psychologists study thinking and other cognitive processes is to measure how fast people can make decisions, solve problems, and distinguishbetween different stimuli.

In typical laboratory studies, people might be asked to name the colors in which words are printed, to scan for a special character in an arrayof letters, or to respond as quickly as possible about whether statements are true or false.

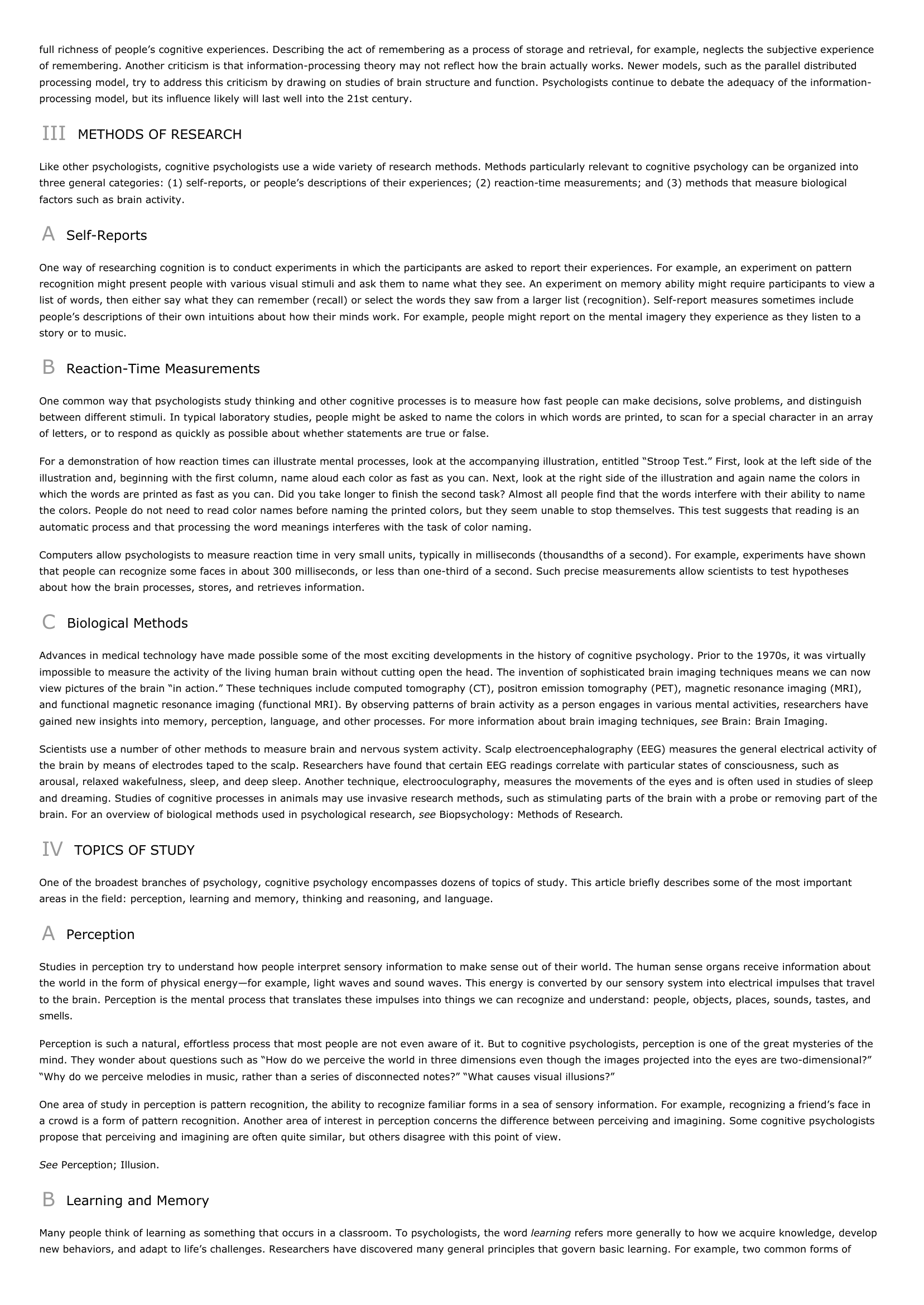

For a demonstration of how reaction times can illustrate mental processes, look at the accompanying illustration, entitled “Stroop Test.” First, look at the left side of theillustration and, beginning with the first column, name aloud each color as fast as you can.

Next, look at the right side of the illustration and again name the colors inwhich the words are printed as fast as you can.

Did you take longer to finish the second task? Almost all people find that the words interfere with their ability to namethe colors.

People do not need to read color names before naming the printed colors, but they seem unable to stop themselves.

This test suggests that reading is anautomatic process and that processing the word meanings interferes with the task of color naming.

Computers allow psychologists to measure reaction time in very small units, typically in milliseconds (thousandths of a second).

For example, experiments have shownthat people can recognize some faces in about 300 milliseconds, or less than one-third of a second.

Such precise measurements allow scientists to test hypothesesabout how the brain processes, stores, and retrieves information.

C Biological Methods

Advances in medical technology have made possible some of the most exciting developments in the history of cognitive psychology.

Prior to the 1970s, it was virtuallyimpossible to measure the activity of the living human brain without cutting open the head.

The invention of sophisticated brain imaging techniques means we can nowview pictures of the brain “in action.” These techniques include computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),and functional magnetic resonance imaging (functional MRI).

By observing patterns of brain activity as a person engages in various mental activities, researchers havegained new insights into memory, perception, language, and other processes.

For more information about brain imaging techniques, see Brain: Brain Imaging.

Scientists use a number of other methods to measure brain and nervous system activity.

Scalp electroencephalography (EEG) measures the general electrical activity ofthe brain by means of electrodes taped to the scalp.

Researchers have found that certain EEG readings correlate with particular states of consciousness, such asarousal, relaxed wakefulness, sleep, and deep sleep.

Another technique, electrooculography, measures the movements of the eyes and is often used in studies of sleepand dreaming.

Studies of cognitive processes in animals may use invasive research methods, such as stimulating parts of the brain with a probe or removing part of thebrain.

For an overview of biological methods used in psychological research, see Biopsychology: Methods of Research .

IV TOPICS OF STUDY

One of the broadest branches of psychology, cognitive psychology encompasses dozens of topics of study.

This article briefly describes some of the most importantareas in the field: perception, learning and memory, thinking and reasoning, and language.

A Perception

Studies in perception try to understand how people interpret sensory information to make sense out of their world.

The human sense organs receive information aboutthe world in the form of physical energy—for example, light waves and sound waves.

This energy is converted by our sensory system into electrical impulses that travelto the brain.

Perception is the mental process that translates these impulses into things we can recognize and understand: people, objects, places, sounds, tastes, andsmells.

Perception is such a natural, effortless process that most people are not even aware of it.

But to cognitive psychologists, perception is one of the great mysteries of themind.

They wonder about questions such as “How do we perceive the world in three dimensions even though the images projected into the eyes are two-dimensional?”“Why do we perceive melodies in music, rather than a series of disconnected notes?” “What causes visual illusions?”

One area of study in perception is pattern recognition, the ability to recognize familiar forms in a sea of sensory information.

For example, recognizing a friend’s face ina crowd is a form of pattern recognition.

Another area of interest in perception concerns the difference between perceiving and imagining.

Some cognitive psychologistspropose that perceiving and imagining are often quite similar, but others disagree with this point of view.

See Perception; Illusion.

B Learning and Memory

Many people think of learning as something that occurs in a classroom.

To psychologists, the word learning refers more generally to how we acquire knowledge, develop new behaviors, and adapt to life’s challenges.

Researchers have discovered many general principles that govern basic learning.

For example, two common forms of.

»

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- PRINCIPES DE PSYCHOLOGIE, Principles of Psychology, 1855. Herbert Spencer

- synthèse de médiation cognitive et didactique de LENOIR

- Cognitive pluralism

- Depression (psychology).

- Memory (psychology).