french versification

Publié le 14/10/2014

Extrait du document

«

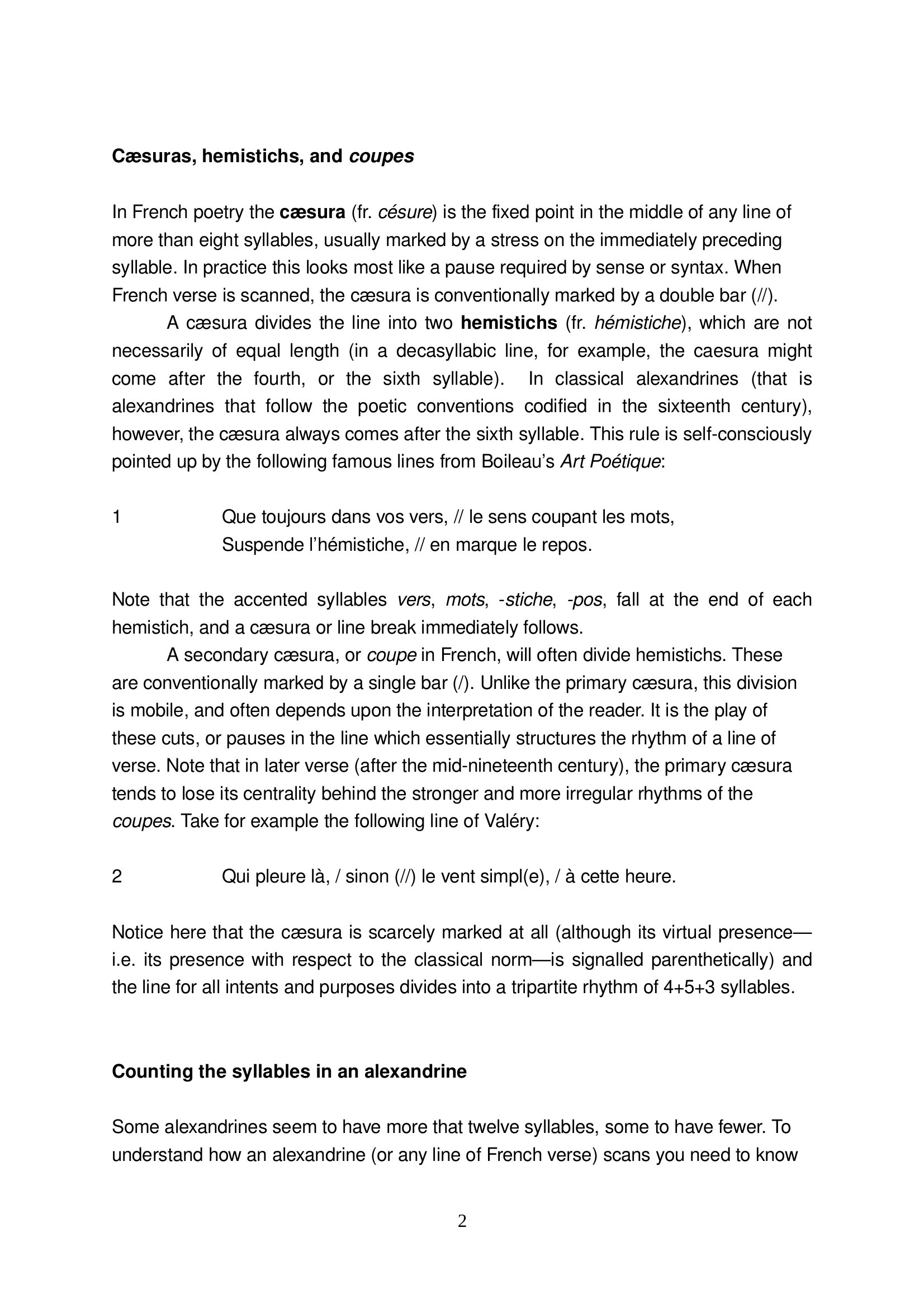

Cæsuras, hemistichs, and coupes

In French poetry the cæsura (fr. césure ) is the fixed point in the middle of any line of

more than eight syllables, usually marked by a stress on the immediately preceding

syllable. In practice this looks most like a pause required by sense or syntax. When

French verse is scanned, the cæsura is conventionally marked by a double bar (//).

A cæsura divides the line into two hemistichs (fr.

h

émistiche ), which are not

necessarily of equal length (in a decasyllabic line, for example, the caesura might

come after the fourth, or the sixth syllable).

In classical alexandrines (that is

alexandrines that follow the poetic conventions codified in the sixteenth century),

however, the cæsura always comes after the sixth syllable. This rule is selfconsciously

pointed up by the following famous lines from Boileau’s Art Po

étique :

1 Que toujours dans vos vers, // le sens coupant les mots,

Suspende l’h

émistiche, // en marque le repos.

Note that the accented syllables vers , mots , stiche , pos , fall at the end of each

hemistich, and a cæsura or line break immediately follows.

A secondary cæsura, or coupe in French, will often divide hemistichs. These

are conventionally marked by a single bar (/). Unlike the primary cæsura, this division

is mobile, and often depends upon the interpretation of the reader. It is the play of

these cuts, or pauses in the line which essentially structures the rhythm of a line of

verse. Note that in later verse (after the midnineteenth century), the primary cæsura

tends to lose its centrality behind the stronger and more irregular rhythms of the

coupes . Take for example the following line of Val

éry:

2 Qui pleure l

à, / sinon (//) le vent simpl(e), / à cette heure.

Notice here that the cæsura is scarcely marked at all (although its virtual presence—

i.e.

its presence with respect to the classical norm—is signalled parenthetically) and

the line for all intents and purposes divides into a tripartite rhythm of 4+5+3 syllables.

Counting the syllables in an alexandrine

Some alexandrines seem to have more that twelve syllables, some to have fewer. To

understand how an alexandrine (or any line of French verse) scans you need to know

2.

»

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- Outils d’analyse : la versification

- Comprendre la versification

- Langue et versification dans les Fables de La Fontaine

- French Open - Sport.

- vers. n.m., élément de base de la versification, caractérisé par