I told her, "The fall play this fall is Hamlet, in case you're interested.

Publié le 06/01/2014

Extrait du document

«

wages

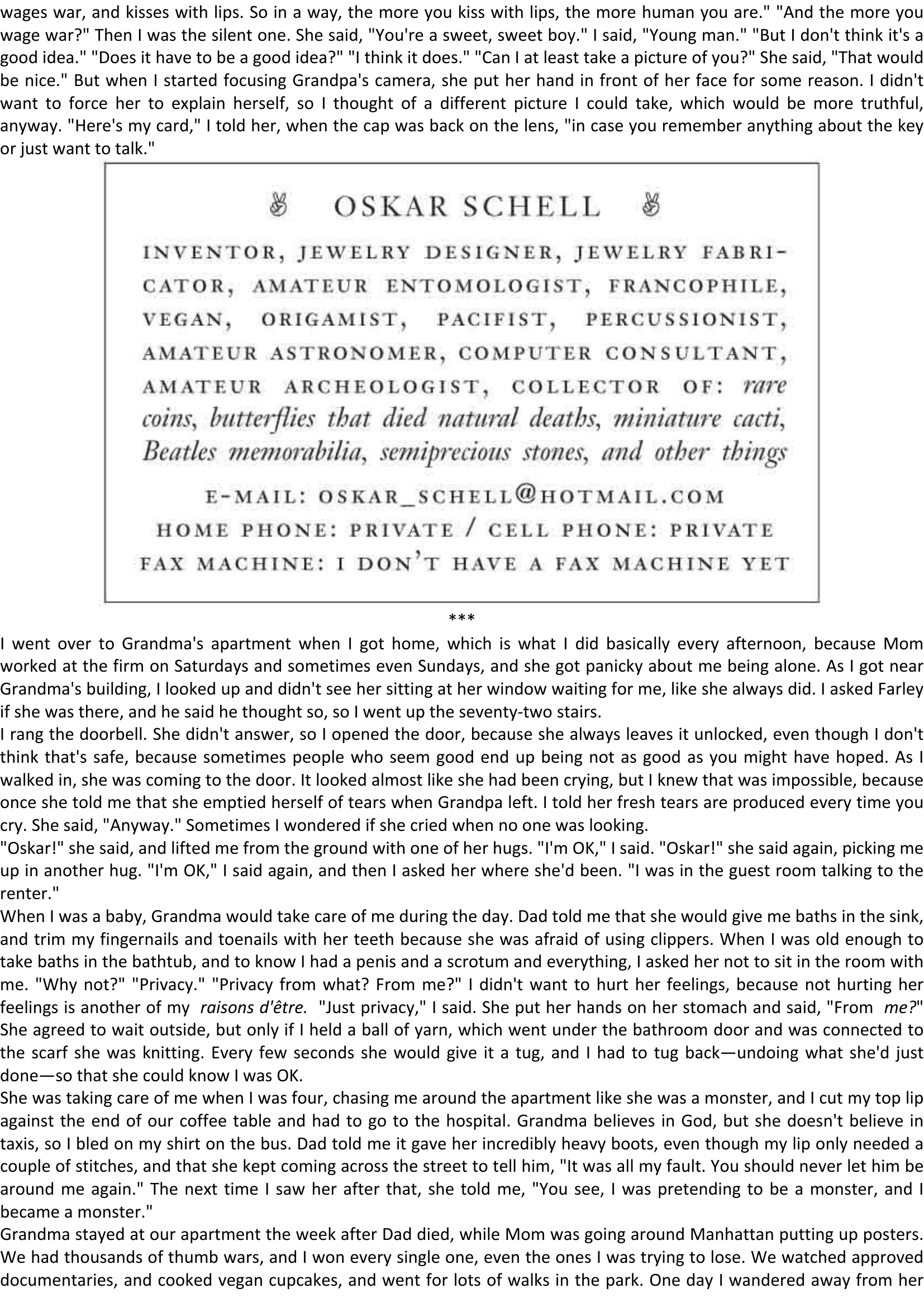

war,andkisses withlips.Soinaway, themore youkisswith lips,themore human youare." "And themore you

wage war?" ThenIwas thesilent one.Shesaid, "You're asweet, sweetboy."Isaid, "Young man.""ButIdon't thinkit'sa

good idea." "Does ithave tobe agood idea?" "Ithink itdoes." "CanIat least takeapicture ofyou?" Shesaid, "That would

be nice." Butwhen Istarted focusing Grandpa's camera,sheputherhand infront ofher face forsome reason.

Ididn't

want toforce hertoexplain herself, soIthought ofadifferent pictureIcould take,which would bemore truthful,

anyway.

"Here'smycard," Itold her, when thecap was back onthe lens, "incase youremember anythingaboutthekey

or just want totalk." ***

I went overtoGrandma's apartmentwhenIgot home, whichiswhat Idid basically everyafternoon, becauseMom

worked atthe firm onSaturdays andsometimes evenSundays, andshegotpanicky aboutmebeing alone.

AsIgot near

Grandma's building,Ilooked upand didn't seehersitting ather window waitingforme, likeshe always did.Iasked Farley

if she was there, andhesaid hethought so,soIwent upthe seventy-two stairs.

I rang thedoorbell.

Shedidn't answer, soIopened thedoor, because shealways leavesitunlocked, eventhough Idon't

think that's safe,because sometimes peoplewhoseem goodendupbeing notasgood asyou might havehoped.

AsI

walked in,she was coming tothe door.

Itlooked almostlikeshe had been crying, butIknew thatwasimpossible, because

once shetold methat sheemptied herselfoftears when Grandpa left.Itold herfresh tearsareproduced everytimeyou

cry.

She said, "Anyway." Sometimes Iwondered ifshe cried when noone was looking.

"Oskar!" shesaid, andlifted mefrom theground withoneofher hugs.

"I'mOK," Isaid.

"Oskar!" shesaid again, picking me

up inanother hug."I'mOK," Isaid again, andthen Iasked herwhere she'dbeen.

"Iwas inthe guest roomtalking tothe

renter."

When Iwas ababy, Grandma wouldtakecareofme during theday.

Dadtoldmethat shewould givemebaths inthe sink,

and trim myfingernails andtoenails withherteeth because shewas afraid ofusing clippers.

WhenIwas oldenough to

take baths inthe bathtub, andtoknow Ihad apenis andascrotum andeverything, Iasked hernot tosit inthe room with

me.

"Why not?""Privacy." "Privacyfromwhat? Fromme?" Ididn't wanttohurt herfeelings, becausenothurting her

feelings isanother ofmy raisons

d'être.

"Just

privacy," Isaid.

Sheputherhands onher stomach andsaid, "From me? "

She agreed towait outside, butonly ifIheld aball ofyarn, which wentunder thebathroom doorandwas connected to

the scarf shewas knitting.

Everyfewseconds shewould giveitatug, andIhad totug back—undoing whatshe'd just

done—so thatshecould knowIwas OK.

She was taking careofme when Iwas four, chasing mearound theapartment likeshe was amonster, andIcut mytop lip

against theend ofour coffee tableandhad togo tothe hospital.

Grandma believesinGod, butshe doesn't believein

taxis, soIbled onmy shirt onthe bus.

Dadtoldmeitgave herincredibly heavyboots, eventhough myliponly needed a

couple ofstitches, andthat shekept coming acrossthestreet totell him, "Itwas allmy fault.

Youshould neverlethim be

around meagain." Thenext time Isaw herafter that,shetold me,"You see,Iwas pretending tobe amonster, andI

became amonster."

Grandma stayedatour apartment theweek afterDaddied, while Momwasgoing around Manhattan puttingupposters.

We had thousands ofthumb wars,andIwon every single one,even theones Iwas trying tolose.

Wewatched approved

documentaries, andcooked vegancupcakes, andwent forlots ofwalks inthe park.

OnedayIwandered awayfromher.

»

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- With the fall of communism the collapse of trade with the former USSR plunged this country into serious economic difficulties.

- The fall of the Berlin Wall on 9th November 1989 was one of the major political events at the end of this century.

- These poems explore encounters between the speaker or a character and a force that is greater than he is – How do the poets develop and contemplate this experience? Refer to the details of language and effect as you compare these poems.

- HAMLET by William Shakespeare Extract 3, 2.2. 364 to the end of the play: Hamlet and the players.

- litterature.pdf : The play Macbeth was written by William shakespeare