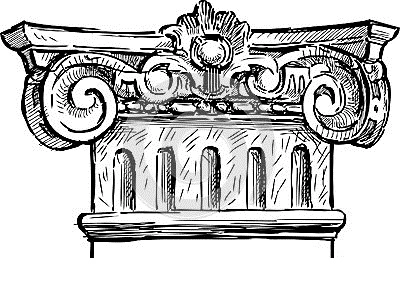

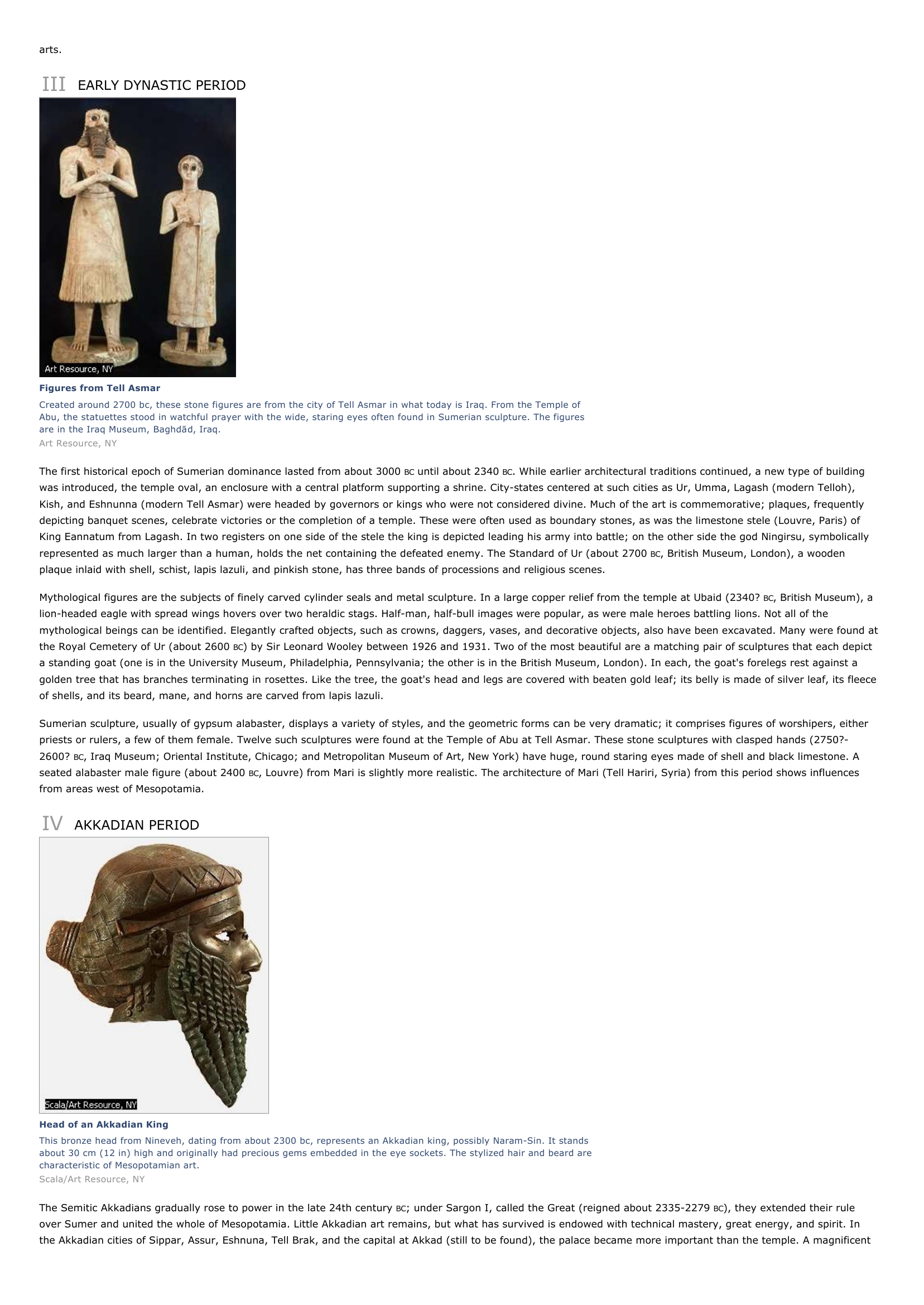

Mesopotamian Art and Architecture I INTRODUCTION Mesopotamian Art and Architecture, the arts and buildings of the ancient Middle Eastern civilizations that developed in the area (now Iraq) between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers from prehistory to the 6th century BC. The lower parts of the Mesopotamian region encompassed a fertile plain, but its inhabitants perpetually faced the dangers of outside invaders, extremes in temperature, drought, violent thunderstorms and rainstorms, floods, and attacks by wild beasts. Their art reflects both their love and fear of these natural forces, as well as their military conquests. Dotting the plains were urban centers; each was dominated by a temple, which was both a commercial and a religious center, but gradually the palace took over as the more important structure. The soil of Mesopotamia yielded the civilization's major building material--mud brick. This clay also was used by the Mesopotamians for their pottery, terra-cotta sculpture, and writing tablets. Few wooden artifacts have been preserved. Stone was rare, and certain types had to be imported; basalt, sandstone, diorite, and alabaster were used for sculpture. Metals such as bronze, copper, gold, and silver, as well as shells and precious stones, were used for the finest sculpture and inlays. Stones of all kinds--including lapis lazuli, jasper, carnelian, alabaster, hematite, serpentine, and steatite--were used for cylinder seals. The art of Mesopotamia reveals a 4000-year tradition that appears, on the surface, homogeneous in style and iconography. It was created and sustained, however, by waves of invading peoples who differed ethnically and linguistically. Each of these groups made its own contribution to art until the Persian conquest of the 6th century BC. The first dominant people to control the region and shape its art were the non-Semitic Sumerians, followed by the Semitic Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians. Control and artistic influences at times extended to the Syro-Palestinian coast, and techniques and motifs from outlying areas had an impact on Mesopotamian centers. As other peoples invaded the region, their art was shaped by native Mesopotamian traditions. II PREHISTORIC PERIOD Mesopotamian Urn This Mesopotamian terra-cotta urn (Iraq Museum, Baghd? d) from the Neolithic Period dates back to between 5000 and 3000 bc. Found in the Middle East, the urn exhibits a design representative of ancient Persian art. Called "animal style," the decoration on the vase features animals, in this case fish, used in a symbolic manner. Because ancient nomadic tribes in the Middle East left no written records or permanent monuments, the artwork buried with their dead provides the most useful information about them. Scala/Art Resource, NY The earliest architectural and artistic remains known to date come from northern Mesopotamia from the proto-Neolithic site of Qermez Dere in the foothills of the Jebel Sinjar. Levels dating to the 9th millennium BC have revealed round sunken huts outfitted with one or two plastered pillars with stone cores. When the buildings were abandoned, human skulls were placed on the floors, indicating some sort of ritual. Mesopotamian art of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods (7000?-3500? BC), before writing was fully developed, is designated by the names of archaeological sites: Hassuna, in the north, where houses and painted pottery were excavated; S?marr?', where figurative and abstract designs on pottery may have had religious significance; and Tell Halaf, where seated female figures (presumed to be mother goddesses) and painted pottery were made. In the south, the early ages are called Ubaid (5500?-4000? BC) and early and middle Uruk (4000?-3500? BC). Ubaid culture is also represented by dark-painted light pottery found first at Ubaid as well as at Ur, Uruk, Eridu, and Uqair. Early in the long sequence of archaeological levels excavated at Eridu a small square sanctuary was uncovered (5500? BC); it had been rebuilt with a niche with a platform, which could have supported a cult statue, and an offering table nearby. Subsequent temple structures built on top of it are more complex, with a central cella (sacred chamber) surrounded by small rooms with doorways; the exterior was decorated with elaborate niches and buttresses, typical features of Mesopotamian temples. Clay figures from the Ubaid period include a man from Eridu and, from Ur, a woman holding a child. Artifacts from the late Uruk and Jamdat Nasr periods, also known as the Protoliterate period (about 3500-2900 BC), have been found at several of the sites mentioned above, but the major site was the city of Uruk, modern Al Wark?' or the biblical Erech. The major building from level five at Uruk (about 3500 BC) is the Limestone Temple; its superstructure is not preserved, but limestone slabs on a layer of stamped earth show that it was niched and monumental in size, measuring 76 x 30 m (250 x 99 ft). Some buildings at Uruk of level four were decorated with colorful cones inset into the walls to form geometric patterns. Another technique that was used was whitewashing, as in the White Temple, which gets its name from its long, narrow, whitewashed inner shrine. It was built in the area of Uruk dedicated to the Sumerian sky god Anu. The White Temple stood about 12 m (40 ft) above the plain, on a high platform, prefiguring the ziggurat--a stepped tower, the typical Mesopotamian religious structure that was intended to bring the priest or king nearer to a particular god, or to provide a platform where the deity could descend to visit the worshipers. A few outstanding stone sculptures were unearthed at Uruk. The most beautiful is a white limestone head of a woman or goddess (about 3500-3000 Baghd? d), with eyebrows, large open eyes, and a central part in her hair, all intended for inlay. A tall alabaster vase (about 3500-3000 BC, BC, Iraq Museum, Iraq Museum) with horizontal bands, or registers, depicts a procession at the top, with a king presenting a basket of fruit to Inanna, goddess of fertility and love, or her priestess; nude priests bringing offerings in the central band; and at the bottom a row of animals over a row of plants. In the late Uruk period, the cylinder seal was introduced, probably in close association with the first use of clay tablets. The cylinder remained the standard Mesopotamian seal shape for the following 3000 years. These small engraved stones of personal identification were rolled along clay to create a continuous pattern or a ritual scene in miniature. The earliest seals display decorative motifs; bulls; priests or kings bringing offerings; sheepherding, hunting, or boating scenes; architecture; and serpent-headed lions and other grotesque figures. Animals, imaginary or real, are depicted with great vitality, even when their forms are abstracted. The seal-cutter's craft was as much an expression of the culture as were the monumental arts. III EARLY DYNASTIC PERIOD Figures from Tell Asmar Created around 2700 bc, these stone figures are from the city of Tell Asmar in what today is Iraq. From the Temple of Abu, the statuettes stood in watchful prayer with the wide, staring eyes often found in Sumerian sculpture. The figures are in the Iraq Museum, Baghd? d, Iraq. Art Resource, NY The first historical epoch of Sumerian dominance lasted from about 3000 BC until about 2340 BC. While earlier architectural traditions continued, a new type of building was introduced, the temple oval, an enclosure with a central platform supporting a shrine. City-states centered at such cities as Ur, Umma, Lagash (modern Telloh), Kish, and Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar) were headed by governors or kings who were not considered divine. Much of the art is commemorative; plaques, frequently depicting banquet scenes, celebrate victories or the completion of a temple. These were often used as boundary stones, as was the limestone stele (Louvre, Paris) of King Eannatum from Lagash. In two registers on one side of the stele the king is depicted leading his army into battle; on the other side the god Ningirsu, symbolically represented as much larger than a human, holds the net containing the defeated enemy. The Standard of Ur (about 2700 BC, British Museum, London), a wooden plaque inlaid with shell, schist, lapis lazuli, and pinkish stone, has three bands of processions and religious scenes. Mythological figures are the subjects of finely carved cylinder seals and metal sculpture. In a large copper relief from the temple at Ubaid (2340? BC, British Museum), a lion-headed eagle with spread wings hovers over two heraldic stags. Half-man, half-bull images were popular, as were male heroes battling lions. Not all of the mythological beings can be identified. Elegantly crafted objects, such as crowns, daggers, vases, and decorative objects, also have been excavated. Many were found at the Royal Cemetery of Ur (about 2600 BC) by Sir Leonard Wooley between 1926 and 1931. Two of the most beautiful are a matching pair of sculptures that each depict a standing goat (one is in the University Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; the other is in the British Museum, London). In each, the goat's forelegs rest against a golden tree that has branches terminating in rosettes. Like the tree, the goat's head and legs are covered with beaten gold leaf; its belly is made of silver leaf, its fleece of shells, and its beard, mane, and horns are carved from lapis lazuli. Sumerian sculpture, usually of gypsum alabaster, displays a variety of styles, and the geometric forms can be very dramatic; it comprises figures of worshipers, either priests or rulers, a few of them female. Twelve such sculptures were found at the Temple of Abu at Tell Asmar. These stone sculptures with clasped hands (2750?2600? BC, Iraq Museum; Oriental Institute, Chicago; and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) have huge, round staring eyes made of shell and black limestone. A seated alabaster male figure (about 2400 BC, Louvre) from Mari is slightly more realistic. The architecture of Mari (Tell Hariri, Syria) from this period shows influences from areas west of Mesopotamia. IV AKKADIAN PERIOD Head of an Akkadian King This bronze head from Nineveh, dating from about 2300 bc, represents an Akkadian king, possibly Naram-Sin. It stands about 30 cm (12 in) high and originally had precious gems embedded in the eye sockets. The stylized hair and beard are characteristic of Mesopotamian art. Scala/Art Resource, NY The Semitic Akkadians gradually rose to power in the late 24th century BC; under Sargon I, called the Great (reigned about 2335-2279 BC), they extended their rule over Sumer and united the whole of Mesopotamia. Little Akkadian art remains, but what has survived is endowed with technical mastery, great energy, and spirit. In the Akkadian cities of Sippar, Assur, Eshnuna, Tell Brak, and the capital at Akkad (still to be found), the palace became more important than the temple. A magnificent copper head from Nineveh (Iraq Museum), probably representing Naram-Sin (reigned about 2255-2218 BC), Sargon's grandson, emphasizes the nobility of these Akkadian kings, who took on a godlike aspect. Naram-Sin is also the subject of a skillfully executed sandstone stele (Louvre), a record of one of his victories in the mountains. He wears a horned helmet symbolic of divinity, and, unlike the iconography of the Stele of Eannatum, here the deity is not credited with his military success. The celestial powers are merely hinted at by sun-stars over a mountain peak. The rhythmic movement of Naram-Sin's triumphant army up the mountain, with the enemy falling downward, is perfectly adapted to the shape of the stone. Mesopotamian Cylindrical Seal Many types of stone were used in Mesopotamia to make seals in the shape of a cylinder. The design was incised in the seal, which was then rolled across wax or clay to produce a raised image, as shown here. Many of the Mesopotamian seals depicted a deity or religious activity. This cylinder seal of black marble belonged to an Akkadian king and dates from between 2340 and 2100 bc. It is in the Louvre in Paris, France. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The most significant Akkadian innovations were those of the seal cutters. The minimal space of each seal is filled with action: Heroes and gods grapple with beasts, slay monsters, and drive chariots in processions. A new Akkadian theme, developed and continued in the periods to follow, was the presentation scene, in which an intermediary or a personal deity presents another figure behind him to a more important seated god. Except for stories from the Gilgamesh epic, many myths that are depicted have not been interpreted. V NEO-SUMERIAN PERIOD Portrait of Gudea Gudea, who ruled the Sumerian city of Lagash during the 2100s bc, ranks among the most familiar of Mesopotamian leaders because of the numerous portrait sculptures of him. Carved in hard black stone, these portraits show the rounded curves of the face and some of the musculature beneath the skin. Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden After ruling for about a century and a half, the Akkadian Empire fell to the nomadic Guti, who did not centralize their power. This enabled the Sumerian cities of Uruk, Ur, and Lagash to reestablish themselves, leading to a Neo-Sumerian age, also known as the 3rd Dynasty of Ur (about 2112-2004 BC). made of baked and unbaked brick and incorporating ziggurats were built at Ur, Eridu, Nippur, and Uruk. Gudea (2144?-2124? a ruler of Lagash, partly BC), Imposing religious monuments contemporary with Ur-Nammu, the founder of the 3rd Dynasty of Ur, is known from more than 20 statutes of himself in hard black stone, dolomite and diorite. His hands are clasped in the old Sumerian style, but the rounded face and slight musculature in the arms and shoulders show the sculptor's will to depict form in this difficult medium with more naturalism than had his predecessors. Other sculptures and reliefs are quite static, except those that depict hybrid figures combining human and animal features. The most lively are small terra-cotta plaques and figurines--worshipers holding animal sacrifices, legendary heroes, musicians, and even a woman nursing a baby. VI OLD BABYLONIAN PERIOD Stele of Hammurabi The code of Hammurabi is engraved on the black basalt of this stele, which is 2.25 m (7 ft 5 in) high and was made in the first half of the 18th century bc. The top portion shown here depicts Hammurabi with Shamash, the sun god. Shamash is presenting to Hammurabi a staff and ring, which symbolize the power to administer the law. Giraudon/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York With the decline of the Sumerians, the land was once more united by Semitic rulers (about 2000-1600 The relief figure of the king on his famous law code (first half of the 18th century BC, BC), the most important of whom was Hammurabi of Babylon. Louvre) is not much different from the Gudea statues (even though his hands are unclasped), nor is he depicted with an intermediary before the sun god Shamash. The most original art of the Babylonian period came from Mari and includes temples and a palace, sculptures, metalwork, and wall painting. As in much of Mesopotamian art, the animals are more lifelike than the human figures. Small plaques from Mari and other sites depict musicians, boxers, a carpenter, and peasants in scenes from everyday life. These are far more realistic than formal royal and religious art. VII KASSITE AND ELAMITE DYNASTIES The Kassites, a people of non-Mesopotamian origin, were present in Babylon shortly after Hammurabi's death but did not replace the Babylonian rulers until about 1600 BC. The Kassites adapted themselves to their environment and its art. The Elamites, from western Iran, destroyed the Kassite Kingdom about 1150 BC; their art also displays a provincial imitation of earlier styles and iconography. Indeed, their admiration of Akkadian and Babylonian art inspired them to carry off the Stele of NaramSin and the Code of Hammurabi to their capital of S? sa. VIII ASSYRIAN EMPIRE Mesopotamian Relief The palaces of ancient Mesopotamia were covered with reliefs that told stories. These narrative reliefs, carved from alabaster, usually depicted scenes from the lives of the kings. This relief, once part of the palace at Dur Sharrukin, now Khorsabad, shows Sargon II (721-705 bc) with one of his subjects. Giraudon/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The early history of the art of Assyria, from the 18th to the 14th century BC, is still largely unknown. Middle Assyrian art (1350-1000 BC) shows some dependence on established Babylonian stylistic traditions: Religious subjects are presented rigidly, but secular themes are depicted more naturalistically. For temple architecture, the ziggurat was popular with the Assyrians. At this time the technique of polychromed glazing of bricks was used in Mesopotamia; this technique later resulted in the typical Neo-Babylonian architectural decoration of entire structures with glazed bricks. Motifs of the sacred tree and crested griffins, used in cylinder seals and palace wall paintings, may have come from the art of the Mitanni, a northern Mesopotamian Aryan kingdom. Unlike earlier representations of vegetation, plant ornamentation is highly stylized and artificial. Symbols frequently replace the gods. Much of the art and architecture was commissioned by Tukulti-Ninurta I (r. 1244-1207 BC) at Assur and at Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, his own residence. In the artwork at both locations, the distance between the gods and humans is emphasized. The narrative frieze, which was derived from the scenes on steles and seals, became the most important aspect of Assyrian art. The genius of Assyrian art flowered in the Neo-Assyrian period, 1000-612 (reigned 883-859 BC), BC, a time of great builders. The first of the great late Assyrian kings was Ashurnasirpal II who built at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu or Calah of the Bible). The walls of Nimrud encompassed an area of about 360 hectares (890 acres) which included the citadel, with the main royal buildings like his Northwest Palace, which was decorated with relief sculptures. Sargon II (reigned 722-705 BC) ruled from the city of Khorsabad (ancient Dur-Sharrukin), which covered 2.6 sq km (1 sq mi) and was surrounded by a wall with seven gates, three of them decorated with reliefs and glazed bricks. In the city was his palace of more than 200 rooms and courts, 1 large temple, and lesser temples and residences. Only part of the complex was completed when he died. His son and successor Sennacherib (reigned 705-681 BC) moved the capital to Nineveh where he built his "Palace without Rival," also known as the Southwest Palace. The North Palace at Nineveh was built by Ashurbanipal (reigned 668-627 BC). These Assyrian kings adorned their palaces with magnificent reliefs. Gypsum alabaster, native to the Assyrian region of the upper Tigris River, was more easily carved than the hard stones used by the Sumerians and Akkadians. Royal chronicles of the king's superiority in battle and in the hunt were recounted in horizontal bands with cuneiform texts, carved on both the exterior and interior walls of the palace, in order to impress visitors. The viewer was greeted by huge guardian sculptures at the gate; the guardians were hybrid genii, winged human-headed lions or bulls with five legs (for viewing both front and side) as known from Nimrud and Khorsabad. At times mythological figures are portrayed, a Gilgamesh-like figure with the lion cub, or a worshiper bringing a sacrifice, such as the idealized portrait from Khorsabad of Sargon II with an ibex (about 710 BC, Louvre). The primary subject matter of these alabaster reliefs, however, is purely secular: the king hunting lions and other animals, the Assyrian triumph over the enemy, or the king feasting in his garden, as in the scene (7th century BC, British Museum) of Ashurbanipal from Nineveh. The king's harpist and birds in the trees make music for the royal couple, who sip wine under a vine, while attendants with fly whisks keep the reclining king and seated queen comfortable. Nearby is a sober reminder of Assyrian might--the head of the king of Elam, hanging from a tree. Sculptors were at their best in depicting hunting scenes, for their observation of real beasts was even more profound than their imagination in creating hybrid beings. The finest animal studies from the ancient world are the dying lion and lioness (about 668 BC, British Museum), details of a hunt from Ashurbanipal's palace at Nineveh. Other reliefs from this monument depict real events: battles, the siege and capture of cities, everyday life in the army camp, the taking of captives, and the harsh treatment meted out to those who resisted conquest. The palace architectural reliefs at Nimrud, Khorsabad, and Nineveh are important not only because they represent the climax of Mesopotamian artistic expression, but because they are valuable as historical documents. Even though cities, seascapes, and landscapes were not rendered with the realism and perspective of later Western artists, the modern observer is still able to reconstruct the appearance of fortified buildings, ships, chariots, horse trappings, hunting equipment, weapons, ritual libations, and costumes through the skill of Assyrian sculptors. The various ethnic groups inhabiting Mesopotamia, Syria, and Palestine in the 1st millennium BC are depicted with great realism and can be identified by their dress, facial features, and hairstyles. Between the 9th-century BC Nimrud reliefs and the 7th-century BC Nineveh reliefs, stylistic changes took place. In the earlier scenes, armies are represented by a few soldiers only, without regard to the relative size of humans and architecture. Figures are in bands, one above the other, to suggest space. In the Nineveh scenes, the figures, carved in lower relief, fill the entire picture plane. Not only is there more detail, but at times figures overlap, giving the viewer a sense of people and animals in real space. The art of the late Assyrian seal cutter is a combination of realism and mythology. Even the naturalistic scenes contain symbols of the gods. Beautiful ivory carvings, found especially at Nimrud but also at Khorsabad, were also made in this period. Among the Nimrud ivories was a pair of plaques, each depicting a lioness attacking an Ethiopian (Iraq Museum and British Museum). They are about 10 cm high (about 4 in) and carved in ivory, partly gilded and inlaid with lapis lazuli and red carnelian. These exquisite objects may have originated outside of Assyria, for they resemble Syro-Phoenician crafted objects found at Arslan Tash on the upper Euphrates and at Samaria, capital of the Israelite kingdom. The lioness plaques incorporate Egyptian iconography and are examples of the best Phoenician craftsmanship. The British Museum piece has the Phoenician letter aleph on the base, presumably a fitter's mark. They were either imported from Phoenicia or possibly made by Phoenician craftsmen at the Assyrian court. Thousands of ivory carvings displaying a variety of styles have been recovered at Nimrud. Many, such as the lioness plaques, were thrown down one of two wells in the Northwest palace when the city was sacked around 612 BC. The art of the peoples who lived on the fringes of the Assyrian Empire at times lacks the aesthetic appeal of that of the capital. In Tell Halaf, a local ruler's palace was decorated with weird reliefs and sculpture in the round; among the hybrids is a scorpion man. At the site of Tell Ahmar in northern Syria, ancient Til Barsip (Assyrian Kar Shalmaneser), a palace decorated extensively with Assyrian wall paintings was uncovered. Some of the paintings are attributed to the mid-8th century rebuilding by Assurbanipal in the 7th century BC. BC; others to a From the earlier building are scenes with winged genii, the defeat of the enemy and their merciless execution, audiences granted to officials, and scribes recording booty from subjugated nations. The paintings in Khorsabad were more formal--repeat patterns in bands are topped by two figures paying homage to a deity. Excavations in Lorest?n, the mountainous region of western Iran, yielded fine bronzes of fantastic creatures, probably made in the middle or late Assyrian period. These were used as ornaments for horses, weapons, and utensils. IX SYRIAN, PHOENICIAN, AND PALESTINIAN ART Syria, Phoenicia, and Palestine were on the land route between Asia Minor and Africa, and the ancient art of this area always shows the influence of those who conquered, passed through, or traded with its inhabitants. Mesopotamian-style cylinder seals from the Jamdat Nasr period were found at Megiddo in Israel and at Byblos, the capital of Phoenicia; in a later period the Hurrians of northern Syria specialized in seal cutting. Pottery, works in stone, and scarabs were influenced by dynastic Egypt beginning in the 29th century BC. Bronze figurines from Byblos of the early 2nd millennium are more distinctly Phoenician, as are daggers and other ceremonial weapons found there. Although the motifs used by local artisans came from beyond the immediate region--Crete (Kríti), Egypt, the Hittite Empire, and Mesopotamia--the technique embodied in crafted objects found at Byblos and Ugarit (with its Hurrian and Mitanui cultural strains) is distinctly Phoenician. Phoenician goldsmiths and silversmiths were skilled artisans, but the quality of their work depended on their clientele. Ivory work was always of the highest standards, probably because of Egyptian competition. Phoenicians sold their wares all over the Middle East, and the spread of Middle Eastern style and iconography, like the alphabet, can be attributed to these great traders of antiquity. X NEO-BABYLONIAN PERIOD Ishtar Gate The Ishtar Gate was originally part of the temple to Bel, built by Nebuchadnezzar in about 575 bc in Babylon. The gate, which has been completely restored, is made of glazed brick tiles with layers of tile used to create the figures of the bull of Adad and the dragon of Marduk, which alternate across the surface. The restored gate is now part of the collection of the Staatliche Museen in Berlin. Gian Berto Vanni/Art Resource, NY (626-539 BC). The Babylonians, in coalition with the Medes and Scythians, defeated the Assyrians in 612 BC and sacked Nimrud and Nineveh. They did not establish a new style or iconography. Boundary stones depict old presentation scenes or the images of kings with symbols of the gods. Neo-Babylonian creativity manifested itself architecturally at Babylon, the capital. This huge city, destroyed (689 BC) by the Assyrian Sennacherib, was restored by Nabopolassar and his son Nebuchadnezzar II. Divided by the Euphrates, it took 88 years to build and was surrounded by outer and inner walls. Its central feature was Esagila, the temple of Marduk, with its associated seven-story ziggurat Etemenanki, popularly known later as the Tower of Babel. The ziggurat reached 91 m (300 ft) in height and had at the uppermost stage a temple (a shrine) built of sun-dried bricks and faced with baked bricks. From the temple of Marduk northward passed the processional way, its wall decorated with enamelled lions. Passing through the Ishtar Gate, it led to a small temple outside the city, where ceremonies for the New Year Festival were held. West of the Ishtar Gate were two palace complexes; east of the processional way lay, since the times of Hammurabi, a residential area. Like its famous Hanging Gardens, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, at the palace of Nebuchadnezzar II, little of the city remains. The Ishtar Gate (575? BC) is one of the few surviving structures. The glazed-brick facade of the gate and the processional way that led up to it were excavated by German archaeologists and taken to Berlin, where the monument was reconstructed. The large complex, some 30 m (about 100 ft) long, is on display in the city's Vorderasiatische Museum. On the site of ancient Babylon, restoration of an earlier version of the Ishtar Gate, the processional way, and the palace complex, all constructed of unglazed brick, has been undertaken by the Iraq Department of Antiquities. Nabonidus (reigned 556-539 BC), the last Babylonian king, rebuilt the old Sumerian capital of Ur, including the ziggurat of Nanna, rival to the ziggurat Etemenanki at Babylon. It survived well and its facing of brick has recently been restored. In 539 BC the Neo-Babylonian kingdom fell to the Persian Achaemenid king Cyrus the Great. Mesopotamia beame part of the Persian Empire, and a royal palace was built at Babylon, which was made one of the empire's administrative capitals. Among the remains from Babylon of the time of Alexander the Great, the conqueror of the Persian Empire, is a theater he built at the site known now as Humra. The brilliance of Babylon was ended about 250 Seleucia, built by Alexander's successors. See also Babylon; Iranian Art and Architecture; Seal. Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved. BC when the inhabitants of Babylon moved to