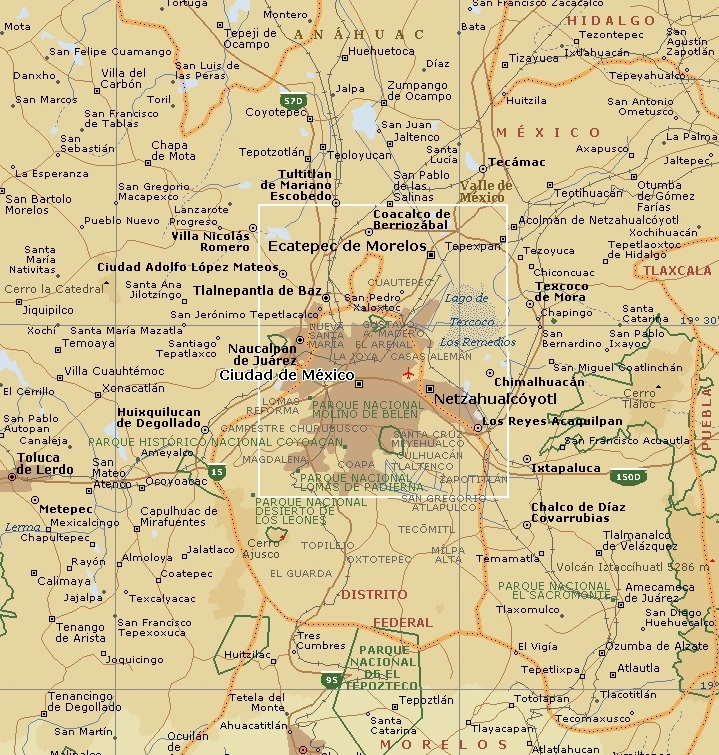

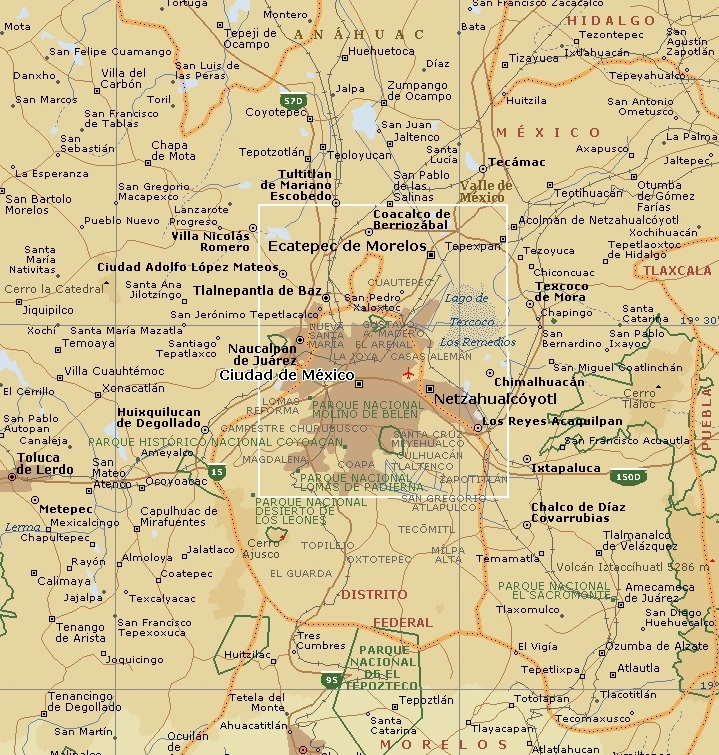

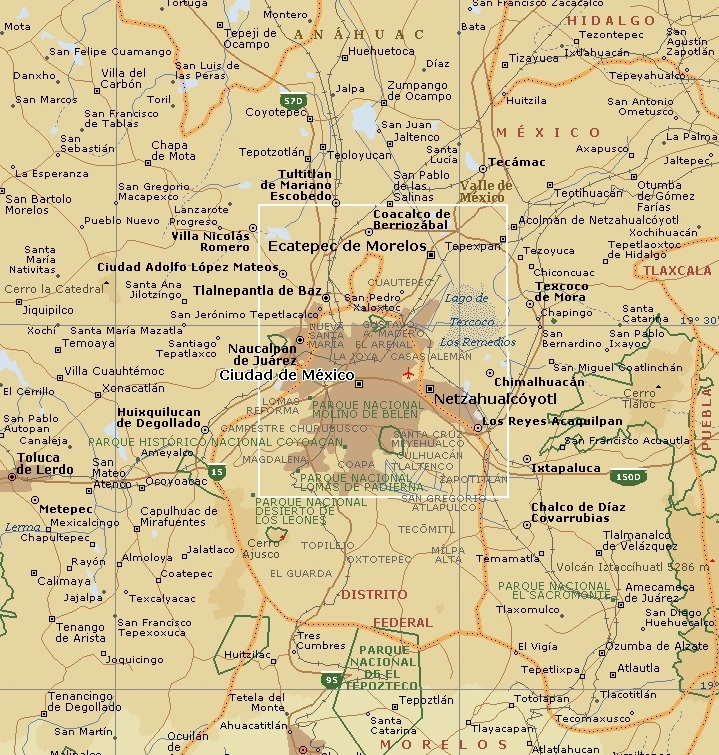

Mexico City - geography. I INTRODUCTION Mexico City, capital of Mexico and the center of the nation's political, cultural, and economic life. Its population of 18.7 million (2003 estimate) makes Mexico City one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world. It is also the seat of Mexico's powerful, centralized federal government. Much of the political decision-making for the nation takes place in Mexico City. Culturally, Mexico City dominates the nation since most of Mexico's leading universities, intellectual magazines, newspapers, museums, theaters, performing arts centers, and publishing firms are located in the capital. Mexico City is built on the ruins of Tenochtitlán, which was the capital of the Aztec Empire. The Aztec developed an advanced civilization and dominated most of Mexico during the 15th and early 16th centuries. In the early 16th century Spanish explorers landed in Mexico and conquered the Aztec. The Spaniards founded Mexico City on the ruins of the Aztec capital, and it soon became the leading urban center in Spain's American colonies. Mexico won its independence in the 1820s, and Mexico City became the capital of the new nation. Mexico City expanded at a phenomenal rate in the 20th century. The metropolitan area absorbed surrounding communities and rural areas to become a sprawling, modern urban center with a thriving economy. The city's rapid growth resulted in major urban problems, including poor housing, pollution, inadequate sanitation, and uncertain water supplies. Mexico City falls within the jurisdiction of the Federal District (in Spanish, Distrito Federal), which is the seat of Mexico's federal government. The Federal District functions as the state and city government for Mexico City and the other communities within its jurisdiction. The Federal District borders the states of Mexico on the north and Morelos on the south. Mexico City is located in the south central portion of the country. It lies at the southern edge of the Mexican central plateau in the Valley of Mexico, a basin at an altitude averaging 2,300 m (7,500 ft). The Valley of Mexico is ringed by a series of mountain ranges. On the eastern edge of the basin are the permanently snowcapped twin volcanoes, Iztaccíhuatl (5,286 m/17,343 ft) and Popocatépetl (5,452 m/17,887 ft). To the west, the mountains separate the Valley of Mexico from the Valley of Toluca and the Lerma River basin, the present source of much of the city's water. The surrounding mountains can trap air pollution within the valley, particularly when there is a thermal inversion (warmer air passing over the valley and trapping cooler ground air beneath it). Mexico City's climate is fairly consistent and steady, a product of both the city's latitude, which is south of the Tropic of Cancer, and its elevation of 2,239 m (7,347 ft). Although the city is located in a tropical climatic zone, the city's extremely high elevation produces a moderate climate with a narrow range of temperatures. The average annual temperature is 16°C (61°F). The coolest season runs from November to February; the coolest month is January, with average temperatures ranging from a high of 21°C (70°F) to a low of 7°C (44°F). The warmest period is from April to June; the average temperatures in May range from a high of 26°C (78°F) to a low of 12°C (54°F). Mexico City has a distinct rainy season from June through October, during which four-fifths of its annual 850 mm (33 in) of rainfall occurs. II MEXICO CITY AND ITS METROPOLITAN AREA Mexico City covers an area of 1,480 sq km (571 sq mi). It is the central, urban core of the Federal District, which was created around the capital city by the 1824 constitution. The Federal District occupies an area of 1,547 sq km (597 sq mi). However, the larger metropolitan area of the capital extends well into the neighboring states of Mexico and Morelos. The metropolitan area largely fills the basin floor of the Valley of Mexico. Its urban development has engulfed a number of old, once-independent towns, such as Coyoacán, creating surprising pockets of colonial architecture in the midst of 21st-century suburban sprawl. Growth has extended to the western edge of the basin and is beginning to creep up the foothills on its western face. To the south the city has reached the town of Tlalpan on the edge of the valley. To the east, poorer areas stretch for miles in a string of ciudades perdidas (Spanish for "lost cities"). A classic example of the city's unchecked expansion is the sprawling neighboring community of Netzahualcóyotl, in the state of Mexico. Economically and socially an integral part of Mexico City, the settlement was a sparsely populated lake bed in 1960. Its population grew to a little more than 500,000 people in 1970 and then more than doubled to 1,101,619 in 2008, making it one of the largest cities in the country. It had to deal with problems characteristic of much of the greater metropolitan area. In the late 1990s only 10 percent of the streets in Netzahualcóyotl were paved, and few public services were available. The people faced poverty, massive unemployment, malnutrition, and soaring infant mortality rates. Since Aztec times the Zócalo, known officially as the Plaza of the Constitution, has been the hub of Mexico City. During the Aztec Empire, this public square was the point where three great causeways converged to connect the city, which was an island in Lake Texcoco, to the mainland empire. Archaeological excavations have exposed the lower levels of the Aztec pyramids and temples in both the Templo Mayor, just behind the Zócalo, and the Plaza of the Three Cultures, a short distance to the north. The excavations are important not only as archaeological sites but also as symbols of Mexico's rich past. When the Spaniards conquered the Aztec in 1521, the Spaniards destroyed a great Aztec palace and temple at the site. They replaced them with a church and palace. The small, original Spanish church on the north side of the plaza was replaced by the Metropolitan Cathedral, which was built between 1573 and 1813. On the plaza's eastern side is the National Palace, the present seat of the Mexican government. Spanish colonial authorities began building the palace in the late 17th century to replace the residence of the Spanish viceroy (colonial governor), erected by conqueror Hernán Cortés and destroyed by rioters in 1692. Work on the palace continued intermittently throughout the 1900s, and the entrance is now adorned with murals by 20th-century Mexican painter Diego Rivera. A rather austere and daunting public space, the Zócalo is the scene of major public ceremonies and military displays. The Zócalo continues to be filled with significance for many Mexicans. It is a sacred place for Native Americans seeking to identify with their precolonial past. It is also a rallying point for political protesters and the location for massive Independence Day celebrations each year on September 16. Slightly to the west of the Zócalo, in the heart of the city's commercial and shopping district, is the Alameda, a park of tree-lined walks laid out in 1592. The park is bordered on the east by the imposing 19th-century Palace of Fine Arts, with its theater and murals. Also nearby is the 44-story Latin American Tower, downtown Mexico City's tallest structure, which houses professional and commercial offices. Farther to the west is the Paseo de la Reforma, an elegant, tree-lined boulevard that is 60 m (200 ft) wide. Seven landscaped traffic circles, or glorietas, line the Paseo de la Reforma and are marked by monuments honoring Mexico's past. These monuments include landmarks such as the statues of Mexican president Benito Juárez and the "Angel of the Independence," a symbol of Mexico's national identity. The Paseo de la Reforma passes some of Mexico City's finest shops, embassies, and offices on its southwesterly course to the 400-hectare (1,000-acre) Chapultepec Park. Stands of trees fill the park, which has extensive recreational facilities, including a lake, fountains, museums, a zoo, and an astronomical observatory. In precolonial times Aztec emperors used Chapultepec as a retreat. Today it offers some indication of the former natural beauty of the valley. The park houses some of Mexico's most important public buildings, including Chapultepec Castle. Construction of the castle began in 1783. Positioned on the park's highest elevation, the castle functioned as a fortress during colonial times. It once served as the presidential residence and now houses the National Museum of History, which includes murals by 20th-century Mexican painter Juan O'Gorman. Los Pinos, the official residence and working offices of the president, is also on the grounds, but it is not open to the public. Chapultepec Park also contains several museums. The most important is the National Museum of Anthropology. Other museums include Mexico's Museum of Modern Art and the Museum of Natural History. (These museums are described below in the section Education and Culture.) Mexico City's major north-south artery is the Avenida Insurgentes, which stretches 30 km (21 mi). It crosses the Paseo de la Reforma just north of the tourist area known as the Zona Rosa (Spanish for "Pink Zone"). Within this neighborhood are many of the principal hotels, restaurants, and fashionable stores catering to the tourist trade. Southward along the Avenida Insurgentes, various stages of the city's growth can be seen. In Colonia Juárez, just south of the Paseo de la Reforma, are elegant 19thcentury mansions from the era of Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz. Less distinguished housing of pre-1940 vintage is located farther south. Finally, as the Avenida Insurgentes approaches the city's boundaries, more affluent neighborhoods appear, with modern buildings, restaurants, and boutiques. At the southern edge of the city, the National Autonomous University of Mexico straddles the Avenida Insurgentes. On the western part of the campus is the 100,000seat Mexico 68 Olympic Stadium, site of the 1968 Olympic Games. Just east of the Avenida Insurgentes is the university's main library. The building and its famous tile mosaic exterior were designed by Juan O'Gorman. Three-dimensional murals by Diego Rivera adorn the rectory on the main campus slightly farther to the east. Outside the city, in the state of Mexico, lie major archaeological sites, including two important pyramids located at Teotihuacán, the capital of an ancient pre-Aztec civilization. The two pyramids face each other on a north-south axis and are known as the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon. Massive in size and height, they provide an extraordinary view of the surrounding region. Mexico's leading religious shrine is located just north of Mexico City in the community of Gustavo A. Madero (formerly Guadalupe Hidalgo). In this community is a basilica that marks the site of the appearance of the Virgin Mary to an indigenous peasant in 1531. The Virgin of Guadalupe, as the apparition came to be called, became a symbol for Mexican forces fighting to gain independence from Spain in the early 1800s. As the patron saint of Mexico, the Virgin of Guadalupe is revered by millions of Mexicans. The shrine attracts more religious pilgrims than any other site in the country. III POPULATION The population of Mexico City proper was 14,007,495 in 2005. The population of the metropolitan area reached 18.7 million in 2003. The city's population growth was phenomenal during most of the 20th century, spurred by migration from the provinces and a high birth rate. From 1950 through 1970, the city's population grew 4.2 percent a year, from 3,050,000 in 1950 to 6,874,000 in 1970. By 1980 the national census reported 8,831,000 people residing in Mexico City. But from 1970 to 1990 the annual growth rate decreased to only 0.9 percent. In part, the growth rate slowed after the mid-1970s because the government introduced a population control policy. As late as 1970, the government denied that a population problem existed. However, during the administration of Mexican president Luis Echeverría Álvarez (1970-1976) the government began a concerted effort to reduce birth rates, providing information on family planning through the national system of social security hospitals. In the capital, the government began an advertising campaign suggesting smaller families as an ideal. The government also began to encourage the creation of jobs in other regions of Mexico, which led to a sharp decrease in migration into Mexico City. From 1985 to 1990, the Federal District lost over a million people, more than any Mexican state. Nonetheless, in 1990 about 22 percent of the city's population had been born outside the metropolitan region. During the 1980s and 1990s, the average age of the population in the metropolitan area increased as younger residents left Mexico City to pursue economic opportunities elsewhere. The median age in the Federal District was 23 in 1990, higher than any of the states. In 1995 the overall population density was about 6,600 persons per sq km (17,200 per sq mi). In the past, the city center was by far the most densely settled part of the city. However, since the 1940s the outlying areas have absorbed most of the population increase. Not surprisingly, the Federal District is more urban than any of the Mexican states, with 99.7 percent of the population living in communities with more than 2,500 inhabitants. Most of the people who live in Mexico City are mestizos--people of both Spanish and indigenous descent. Nevertheless, variations exist within the mestizo population based on the ratio of Spanish to indigenous ancestry. Most of the people in the city speak Spanish. Mexico City has relatively few individuals who still speak Native American languages, unlike other regions of the country. In 1990 only 1.5 percent of Federal District residents spoke Native American languages, compared to 7.5 percent nationally. The major condition dividing the city's population is wealth. The capital is a city of sharp social contrasts. Wealthy residential sections are characterized by housing and suburban retail centers that rival the most luxurious in the world. A person can travel for miles in the affluent western and southern parts of the city without awareness of being in an underdeveloped nation. These neighborhoods are often in sharp contrast to the poorer sections, where housing is substandard, access to utilities and services is limited, and the standard of living is well below the poverty level. These less affluent neighborhoods are found in the center of the city and to the north and east. Ninety-two percent of the population professes membership in the Roman Catholic Church. Only 3.2 percent are Protestant, and less than 0.3 percent are Jewish. The Roman Catholic Church plays an influential social and cultural role in the city. More residents are members of church-affiliated organizations than of any other type. Led by one of Mexico's cardinals, the diocese of Mexico City is the most important in the country. It frequently publishes statements criticizing political and societal problems and emphasizing the need to reduce economic poverty. IV EDUCATION AND CULTURE Mexico City dominates the country's cultural life with a disproportionate number of universities, museums, and cultural institutions. One-third of Mexico's institutions of higher learning are located in the capital, including its largest and most prestigious universities. Most people who are educated in the capital remain there because universities provide the primary source of employment for cultural leaders in Mexico. The dominant educational institution is the National Autonomous University of Mexico, which moved to its present site, known as University City, in 1952. Its rapid rise in enrollment, from 40,000 in 1960 to 135,000 in the mid-1990s, reflects both the increase in the city's population and the rising aspirations of Mexicans. To accommodate the soaring student enrollments of the 1970s, the government created the Metropolitan Autonomous University, the largest university system in the country. It provides a series of large campuses in various areas of the city, including working-class neighborhoods. These campuses have increased access to higher education among lowerincome social groups. Also of note is the National Polytechnic University. Another institution, the Colegio de México, patterned after the United States university system, is widely known for its graduate program and its research in the social sciences. Mexico City is also home to the National Center of the Arts, opened in 1994. This architecturally impressive complex houses facilities for students of the fine arts, music, film, and drama and contains a library and concert hall. In Mexico, many university campuses are highly political, and student groups often engage in ideological battles or become actively involved in national political issues. Universities are often the sites of strikes by university employees. Several prestigious private colleges, including the Jesuit Ibero-American University and the Anáhuac University, are havens from the social turmoil that frequently grips the large public institutions. While nearly all of the children in Mexico City between the ages of 7 and 13 attend elementary school, one-third never progressed beyond the 6th grade. There is a chronic shortage of school space, which is more acute at the secondary level. School space is in short supply partly because so many people have moved to Mexico City from rural areas. Mexico City has a wide range of museums and cultural attractions. The Templo Mayor museum contains artifacts of the city's early history. Chapultepec Park contains several historical museums, including the world-famous National Museum of Anthropology, whose collection forms a comprehensive history of Mexico's indigenous populations. It is complemented by the National Museum of History housed in Chapultepec Castle, which offers exhibits of Mexican life since the time of the European conquest in the early 1500s. Chapultepec Park has several other museums, including Mexico's Museum of Modern Art, which houses paintings from the 19th and 20th centuries, and the Museum of Natural History, featuring exhibits about Earth and its plants and animals. The Rufino Tamayo Museum, also located in Chapultepec Park, includes the collection of European and American art once owned by Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo. The park also includes the Papalote Children's Museum. This hands-on science museum encourages visitors to take part in interactive exhibits. The Museum of Mexico City is located in the older section of downtown. It is a general museum with an emphasis on the development of the city and history and culture of the Valley of Mexico from prehistoric times through the Mexican revolution. In the Coyoacán neighborhood, the home of Frida Kahlo, one of Mexico's leading painters, is also a popular attraction. Mexico City's outstanding theater is the Palace of Fine Arts. Its imposing marble structure is home to the national opera, national theater, National Symphony Orchestra, and Ballet Folklórico, the official national dance company of Mexico. Murals by celebrated 20th-century Mexican artists, such as Diego Rivera, Juan O'Gorman, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, adorn the Palace. Works by these artists, which feature indigenous Mexican motifs and themes, are exhibited throughout the city in museums and on public buildings. Among the most important sites are the National Palace, the secretariat of public education, the Chapultepec Castle, the Palace of Justice, and the National Museum of History. Mexico City is the center of Mexico's vigorous publishing industry, which benefits from one of the freest publishing climates in Latin America. Two of Latin America's best newspapers, Excélsior and Reforma, are among the dailies published in the city, which also has several television stations and numerous radio stations. The most important libraries are found at the Colegio de México and the National Archives. V RECREATION Many of Mexico City's recreational facilities revolve around family activities. Families use Chapultepec Park intensively, especially on Sundays, when they picnic under the trees, stroll through the eucalyptus glades, or visit the park's zoo, amusement park, and museums. Within the park also is a small lake, where families rent rowboats and dine at waterside restaurants. Southeast of the city are the floating gardens of Xochimilco. The gardens are the last remnants of Lake Texcoco, which once surrounded the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. The floating gardens received their name from the ancient Aztec practice of anchoring baskets of earth in the lake to create new land. Xochimilco's network of canals and small islands serves both as a recreational area and as a reminder that water once covered much of the valley floor. Popular sports in Mexico City include soccer, jai alai (a ball game of Basque origin), and bullfighting. Azteca stadium seats 100,000 people and hosts regular soccer matches. It was the site of the 1970 and 1986 World Cup international soccer championships. The city is home to the world's largest bullfighting arena, the 50,000-seat Plaza Mexico, sometimes called the Monumental Plaza Mexico. VI ECONOMY Mexico City dominates the nation's economy. The Federal District produces a significant portion of Mexico's gross domestic product, or GDP (the total value of goods and services produced in the country). The federal district area accounted for 12 percent of GDP in 1998. Mexico City is the center of a manufacturing belt that stretches from Guadalajara in the west to Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico in the east. Manufactures include textiles, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, electrical and electronic items, steel, and transportation equipment. In addition, a variety of foodstuffs and light consumer goods are produced. The city plays a dominant role in Mexico's banking and finance industries. It is home to Banco de México (federal reserve bank), the Bolsa (stock exchange), and every major banking chain in the country. All major financial services, including insurance companies, are centered in Mexico City. Agriculture, mining, and trade dominated Mexico City's economy for most of its history. An industrial economy began to take root in the early 1900s. However, industry did not become the leading economic activity until government investment programs encouraged large-scale growth of manufacturing and other industrial production in the city in the 1940s and 1950s. During the 1980s, however, the government began to encourage industrial and manufacturing development in other areas of the country in an attempt to reduce pollution and overcrowding in the city. These attempts led to the decline of industrial production and employment in the city. From 1980 to 1988, Mexico City lost almost 100,000 (about 25 percent) of its industrial jobs. Although the city has lost industrial and manufacturing jobs, other sectors of its economy, notably services and commerce, have grown. The concentration of economic activity in the city attracted people from rural areas in search of employment. People moved to the city faster than new jobs were created. Many of these new residents of Mexico City were unskilled workers. They were unable to find employment in the city, contributing to problems of unemployment and underemployment. Mexico City is the hub of Mexico's transportation system. Major highways and railroads radiate from the city to all parts of the country. Benito Juárez International Airport, the capital's only airport, is located just east of the center of the city. It offers direct flights to many world capitals. Bus terminals in the city serve the needs of cross-country travelers and have largely replaced passenger service by rail. Mexico City's motor vehicles produce serious traffic and pollution problems. Commuters within Mexico City are served by a fleet of local buses and a subway system, the Metro, which opened in 1969 with some 40 km (25 mi) of track. During the 1970s, the number of riders increased dramatically, and the Metro expanded its lines. In spite of the expanded system, the Metro is fully used and crowded most hours of the day. VII GOVERNMENT The political structure of Mexico City and the Federal District was formalized by the 1917 constitution. Under the constitution, the Federal District included Mexico City and several suburban cities, and it was governed by the head of the Department of the Federal District. The department was responsible for all activities normally associated with city government, including police, public works, and transportation. The head of the Department of the Federal District exercised the combined powers of mayor of Mexico City and governor of the district. Until the 1990s, the president of Mexico appointed the head of the department. The department became more important as the population of the city grew dramatically, as Mexico City became the center of the country's industrial growth, and as intellectual and professional resources concentrated within its boundaries. The department became one of the largest, most influential federal bureaucracies. Residents of the Federal District became increasingly dissatisfied with a political situation that denied them the right to vote for what, in effect, would be their governor or mayor. In the 1980s and 1990s, the national government enacted reform legislation that transferred control of the Federal District's government from officials appointed by the nation's president to politicians elected directly by the voters of the Federal District. In 1988 residents began electing representatives to an Assembly of the Federal District, a newly created legislative body. However, the assembly exercised little influence on policy decisions affecting the district. The district eventually approved legislation that established an elected position for Mexico City and the Federal District, creating a powerful new political office directly accountable to the residents of the district. The new position was the head of the Federal District (often referred to as the mayor of Mexico City). The first election was held in 1997. Voters elected Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, a member of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), one of Mexico's major opposition parties. VIII CONTEMPORARY ISSUES Among the issues that the government faces, none is more important to Mexicans than the rapid increase in street crime. Although statistics are unreliable, observers agree that robbery, assault, and murder have increased dramatically since 1994. Mexico City has gone from one of the safest metropolitan areas in the world to one of the most dangerous. Health care is also a pressing issue in Mexico City. Nationally, 36 percent of Mexicans had access to health-care coverage in 1995, while 22 percent used such services. In the Federal District, 46 percent of the people had access to health services the same year, but only 18 percent used them. Although the residents in the Federal District have higher than average access to health care, infant mortality rates are among the highest in the nation--21 deaths among 1,000 infants under the age of one. These rates are so high because access to health care is distorted, largely confined to middle and upper classes. Large concentrations of low-income families do not have adequate health care. In addition, Mexico City's extraordinarily high levels of air pollution are particularly detrimental to the health of infants. Homeless children are increasingly an issue, too. Mexico was estimated to have 13,373 children living on the streets in 1995. Adequate housing has long been a problem in the capital, although the Federal District ranks well above the average for the entire country. For example, the average occupant per room was 1.1 in the Federal District in 1995, but 1.5 nationally. More than 75 percent of private homes in the Federal District had 3 or more rooms in 1995, compared to 66 percent nationally. Housing in the Federal District ranks higher than other parts of the country in terms of qualitative services, such as water and sewage. Mexico City, like so many metropolitan areas worldwide, faces problems because workers do not live near where they work. Mexico City has excellent subway and bus systems, but they are inadequate given the number of daily commuters. In addition, the freeway system has not kept pace with the increased use of automobiles. Automobile pollution, which accounts for two-thirds of all air pollution in the city, reduced visibility from more than 16 km (10 mi) in the 1930s to less than 4 km (2.5 mi) in the 1960s. It also has created serious smog problems. Since mountains surround the city, the smog often remains trapped in the valley basin. The government has attempted to alleviate traffic congestion by constructing a controlled-access beltway, the Periférico, along the city's western and southern edges. It has also created a grid of high-volume roads crossing the city at regular intervals. In the late 1980s, the government resorted to a system whereby cars with certain license plates could travel within the city only on selected days. None of these approaches has solved the city's air pollution problems. Air pollution in the city reaches harmful levels more than half the days of the year. IX HISTORY Founded in 1325, the Aztec city of Tenochtitlán was built on an island in Lake Texcoco, the site of present-day Mexico City. The city was the military and administrative center of the Aztec Empire, which included large parts of Mexico and Central America. Tenochtitlán is estimated to have had a population of about 200,000 people, making it one of the world's largest settlements when Europeans first arrived in the Americas in the early 16th century. Tenochtitlán was built around a series of temples and pyramids. It was organized into a series of calpulli (Aztec for "clans"), each forming a loose neighborhood of the city. The calpulli fulfilled different economic roles, and each acted as an army battalion. The Aztec emperor was selected from the calpulli leadership. A Spanish Rule In 1519 a group of Spaniards under the leadership of explorer Hernán Cortés arrived in Mexico. In 1521 Cortés conquered the city in an 85-day siege, during which most of Tenochtitlán was destroyed. When the conquest was complete, the population of the city had dwindled to about 30,000 people as a result of the war and epidemics of unfamiliar European diseases. The Spaniards began to reconstruct the city soon after they conquered it. Like most Spanish colonial cities, Mexico City was laid out on a grid pattern. The cathedral and the principal administrative buildings were built around a central plaza, known today as the Zócalo. The mansions and palaces of the elite, most of whom were appointees from Spain, were located in the streets running off the plaza. The poor lived farther away or slept in the streets, while Native Americans lived in jacales (villages of huts) at the city margins. The new European-style city, renamed Mexico City, became the most important settlement in Spain's American colonies. It served as an administrative center, a major military outpost, and a base for exporting the mineral and agricultural wealth of the Americas to Spain. The city became the capital of the colony of New Spain, which included Mexico, most of Central America, and large sections of what is today the southern United States. Beginning in 1535 a series of royal governors known as viceroys ruled New Spain from Mexico City. The city's upper class grew rich on the profits from Mexican gold and silver mines. Despite problems with disease, famine, and flooding, the city grew. In the 17th century the Spaniards built massive canals to drain Lake Texcoco. The canals reclaimed land and alleviated chronic flooding. The city's population rose gradually, reaching 60,000 by 1600, 105,000 by 1700, and 137,000 by 1800. B The 19th Century Early in the 19th century, Mexico fought an armed struggle to achieve independence from Spain. In 1821 Agustín de Iturbide, a military officer who joined the independence forces, triumphantly entered Mexico City, which had been largely spared the sieges and looting suffered in other parts of the country. Iturbide declared Mexico an independent nation and proclaimed himself emperor. However, his rule became despotic and wasteful, and in less than a year the military forced him to resign. Mexicans adopted a republican constitution in 1824, in which powers were shared between the states and the federal government. The constitution created a national congress, which selected Mexico City as the national capital and created the initial boundaries of the Federal District. B1 Political Instability A tumultuous period followed in the life of the city and the nation. The war for independence left the economy in shambles, and various factions in the country could not agree on the political future of the nation. A struggle for power ensued. Over the next 50 years, more than 30 presidents and 50 governments succeeded one another. Often, two or even three groups claimed jurisdiction simultaneously. This lack of stability made obtaining adequate finances difficult for Mexico City and most other Mexican cities. Lacking funding, the city's services and infrastructure suffered. Such national disarray made Mexico easy prey to foreign intervention. France occupied the capital from 1863 to 1867 and established the Austrian archduke Maximilian briefly as the country's emperor. During his reign, Maximilian dedicated much of the city's treasury to beautification projects and made some lasting changes in the city's appearance. He expanded the palace at Chapultepec Park and built the tree-lined boulevard that is today known as the Paseo de la Reforma. Forces under the control of Mexico's elected president, Benito Pablo Juárez, overthrew and executed Maximilian in 1867. Juárez ruled until his death in 1872, when a struggle for power again erupted among Mexican politicians and military leaders. B2 Presidency of Porfirio Díaz In 1877 Mexico's long turbulent period ended with the presidency of Porfirio Díaz, a military officer who seized the presidency in a coup. Díaz ran the country with a dictatorial hand. His government erected many magnificent public buildings, and Mexico City assumed the look of a European capital. Construction of the Palace of Fine Arts, whose architecture imitated European styles, began under Díaz, as did work on the legislative building (now the Monument to the Revolution), a dominating structure of steel and cement. Prominent architects, both Mexican and European, designed other private and public buildings; these included a national theater, hospitals, churches, and department stores. In the late 1800s and early 1900s the city began to shift to an industrialized base. During the transition, unemployment actually increased as many traditional artisans found themselves without jobs. Housing also became a significant problem; 16 percent of the population rented rooms on a day-to-day basis. Growth in trade and commerce gave rise to a new elite that took the place of the colonial elite, which had been based on wealth from silver and gold. The country's new upper class built homes in the newer suburbs to the south and southwest of the city. Their mansions, like the newly constructed public buildings and monuments, departed from classical Spanish architecture and adopted artistic styles popular in England and France. Among Mexico's elite, the French influence predominated. Upper-class families sent their children to study in Paris, bought household goods produced in Europe, wore the latest fashions from London and Paris, read literature from the continent, hired European chefs, and practiced sports popular in Europe, such as polo. Painting from the period, such as the landscapes of José María Velasco, emulated the trends favored in France and England while incorporating indigenous Mexican subjects. Architecture in the capital was most influenced by the art nouveau movement, which stressed organic decorative patterns, such as intertwined stems or flowers, and emphasized handcrafting as opposed to machine manufacturing. C The 20th Century Although the country was politically stable and its economy improved, Díaz disregarded social problems, creating unrest throughout the country. The value of wages for workers declined from 1877 to 1910. The government never implemented a public education system. Child labor was a serious problem throughout the period; an estimated 12 percent of all textile workers were children. Many working-class Mexicans received their wages as script (a credit slip issued by their employers), forcing them to purchase their food and other necessities from employer-owned stores at inflated prices. Peasants and indigenous Mexicans lived and worked under particularly precarious and oppressive conditions. Many worked under a system of debt peonage, under which they became legally obligated to their employers. This pattern, which resulted in numerous abuses and exploitation, became a form of economic servitude. Many workers wanted the rights to organize and strike in order to demand better pay, fewer hours, and improved working conditions. The government, however, suppressed these working-class demands, which led to a violent revolution in 1910. The Mexican Revolution forced Díaz to leave Mexico for exile and introduced a decade of civil violence. The revolution and its aftermath halted the development of Mexico City. Indeed, the population actually declined between 1910 and 1920. The political revolution led to an equally important revolution in artistic and intellectual circles and the revival of indigenous themes in Mexican artistic and literary schools. Young art students, among them David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco, eventually supported a movement away from paintings on canvas to present their works in large, public formats on the walls of government and private buildings. They rejected European influences, hoping to create works that were both accessible to ordinary Mexicans and oriented toward national themes. This nationalistic movement and the dynamic change in style attracted artists and writers from all over the Americas in the 1920s. By 1920 the political stability had been restored. For a brief period during the 1920s, an elected mayor governed the city, but in 1928 the federal government gave control of the capital to the Department of the Federal District. At this same time, the victors in the revolution, seeking to consolidate their political power, organized a powerful political party, the National Revolutionary Party (PRN). Eventually the PRN became the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). The PRI and its leaders monopolized control over local, state, and national government. For the next 60 years, the party never lost an election for the presidency or the governorship of any state. The party was able to maintain tight control over the administration of the Federal District and Mexico City because the president appointed the head of the Department of the Federal District and the president always belonged to the PRI. In 1921 Mexico City had just over 900,000 residents and was surrounded by miles of rural farms and communities. During the next 50 years, the city's population grew rapidly, as people moved from less developed regions to the capital. The population nearly doubled from 1921 to 1940 and more than doubled again from 1940 to 1960, when the population reached nearly 5 million. As the city grew, much of its colonial and European architecture disappeared. Numerous residences along the major avenues were destroyed to make way for modern office buildings and retail stores. Neighboring communities were incorporated within the city's metropolitan area, and by 1970 Mexico City was no longer surrounded by a rural landscape, but by an extensive megalopolis. This expansion reached beyond the boundaries of the Federal District into the state of Mexico, which surrounds the district on three sides. During the 20th century, the land on which Mexico City was built subsided unevenly at rates of up to 30 cm (12 in) a year. This subsidence resulted from the drainage of Lake Texcoco and the removal of groundwater. As a result, the city sat on spongy soil, which tended to amplify the power of the earthquakes that occurred periodically in the Valley of Mexico. In 1985 a major earthquake, centered on Mexico City itself, caused extensive damage in the central part of the city. Especially hard hit were the older buildings, many of which were not designed to withstand earthquakes. The government of Mexican president Miguel de la Madrid did not respond effectively to the crisis. Many city residents came to believe that the government was more concerned about protecting the damaged buildings from possible looting than about rescuing those trapped in the ruins. Citizens joined together to carry out the rescue efforts themselves, creating a strong sense of community. This informal cooperation eventually became more permanent. Those deprived of housing and employment as a consequence of the earthquake demanded relief from the city's government and organized to support their demands. These organizations became grassroots civic and political groups that eventually promoted the growth of opposition parties in the capital. During the 1980s and 1990s citizens of Mexico City voted in large numbers for presidential candidates from the two leading opposition parties, the National Action Party (PAN) and the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD). In the 1988 presidential elections, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, representing the party that later became the PRD, received the largest number of votes in the Federal District. The citizens of Mexico City also began to demand more self-government for the city. The first concession to returning power more directly to residents was the creation of the Assembly for the Federal District in 1988. The Federal District was divided into districts, each represented by an assembly member. Despite the existence of the Assembly, most power remained in the hands of the head of the Department of the Federal District. As part of an electoral reform package, the federal government agreed to a 1997 election in which citizens would choose the head of the Federal District. The contest for this position became the most significant electoral race in the 1997 national elections. The victor would represent more than 16 million people and would be a potential candidate for a presidential nomination in 2000. Voters elected Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas as head of the Federal District, and he took office in December 1997. His party also won control of the assembly, as well as most of the seats to the national congress that were elected from the Federal District. Although constitutionally the president of Mexico retained the right to appoint the police chief and the attorney general of the Federal District, Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo transferred those decisions to Cárdenas. However, Cárdenas encountered great difficulty coping with the widespread social and economic problems confronting the city. The most important problem for the city residents was the lack of personal security. Although Cárdenas changed police chiefs several times and introduced new forms of policing, including bicycle patrols, his government was unable to reduce crime levels in auto theft, burglaries, and muggings. In 1999 Cárdenas resigned as head of the Federal District to run for president of Mexico. The assembly chose Rosario Robles Berlanga to replace him. Robles was the first female head of the Federal District. In the 2000 election, Andrés Manuel López Obrador was elected head of the federal district. López Obrador resigned as head of the federal district to run for Mexico's presidency in the 2006 elections. He was narrowly defeated. He was succeeded as head of the federal district by Marcelo Luis Ebrard Casaubon, who won election in July and was inaugurated in December. In 2007 Mexico City's legislature approved a law allowing abortion in the first three months of pregnancy. The controversial legislation made Mexico City one of the few places in all of Latin American where abortion was legal. Contributed By: Charles O. Collins Roderic Ai Camp Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.