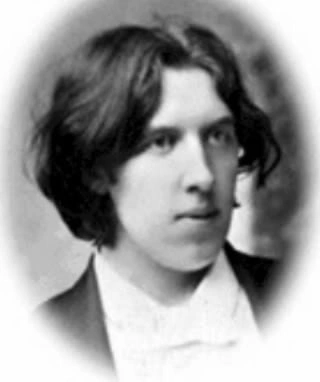

Oscar Wilde: The Picture of Dorian Gray (Sprache & Litteratur).

Publié le 13/06/2013

Extrait du document

Oscar Wilde: The Picture of Dorian Gray (Sprache & Litteratur). Es gebe weder moralische noch unmoralische, sondern nur gut oder schlecht geschriebene Bücher, vermerkte Oscar Wilde im Vorwort zu seinem einzigen Roman The Picture of Dorian Gray (Das Bildnis des Dorian Gray). Das Werk wurde von den meisten Zeitgenossen auch prompt als amoralisch abgelehnt. Es schildert die Geschichte eines Mannes, der - mit ewiger Jugend und Schönheit begnadet, weil sein gemaltes Porträt statt seiner altert - seinen Hedonismus und Narzismus ebenso hemmungs- wie rücksichtslos auslebt und schließlich auch vor dem Mord an Basil Hallward, dem Maler seines Porträts, nicht zurückschreckt. Sein Leben endet in Überdruss und Gewissensqualen. Er zerstört das Gemälde und stirbt (diese Szene ist im vierten Zitat beschrieben). Oscar Wilde: The Picture of Dorian Gray ,,The story is simply this," said the painter after some time. ,,Two months ago I went to a crush at Lady Brandon's. You know we poor artists have to show ourselves in society from time to time, just to remind the public that we are not savages. With an evening coat and a white tie, as you told me once, anybody, even a stockbroker, can gain a reputation for being civilized. Well, after I had been in the room about ten minutes, talking to huge, overdressed dowagers and tedious Academicians, I suddenly became conscious that someone was looking at me. I turned halfway round, and saw Dorian Gray for the first time. When our eyes met, I felt that I was growing pale. A curious sensation of terror came over me. I knew that I had come face to face with someone whose mere personality was so fascinating that, if I allowed it to do so, it would absorb my whole nature, my whole soul, my very art itself. I did not want any external influence in my life. You know yourself, Harry, how independent I am by nature. I have always been my own master; had at least always been so, till I met Dorian Gray. Then - but I don't know how to explain it to you. Something seemed to tell me that I was on the verge of a terrible crisis in my life. I had a strange feeling that Fate had in store for me exquisite joys and exquisite sorrows. I grew afraid, and turned to quit the room. It was not conscience that made me do so; it was a sort of cowardice. I take no credit to myself for trying to escape." (...) ,,Because you have the most marvellous youth, and youth is the one thing worth having." ,,I don't feel that, Lord Henry." ,,No, you don't feel it now. Some day, when you are old and wrinkled and ugly, when thought has seared your forehead with its lines, and passion branded your lips with its hideous fires, you will feel it, you will feel it terribly. Now, wherever you go, you charm the world. Will it always be so? ... You have a wonderfully beautiful face, Mr Gray. Don't frown. You have. And Beauty is a form of Genius - is higher, indeed, than Genius, as it needs no explanation. It is one of the great facts of the world, like sunlight, or spring-time, or the reflection in dark waters of that silver shell we call the moon. It cannot be questioned. It has its divine right of sovereignty. It makes princes of those who have it. You smile? Ah! when you have lost it you won't smile ... People say sometimes that Beauty is only superficial. That may be so. But at least it is not so superficial as Thought is. To me, Beauty is the wonder of wonders. It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible ... Yes, Mr Gray, the gods have been good to you. But what the gods give they quickly take away. You have only a few years in which to live really, perfectly, and fully. When your youth goes, your beauty will go with it, and then you will suddenly discover that there are no triumphs left for you, or have to content yourself with those mean triumphs that the memory of your past will make more bitter than defeats. Every month as it wanes brings you nearer to something dreadful. Time is jealous of you, and wars against your lilies and your roses. You will become sallow, and hollow-checked, and dulleyed. You will suffer horribly ... Ah! (...) Our limbs fail, our senses rot. We degenerate into hideous puppets, haunted by the memory of the passions of which we were too much afraid, and the exquisite temptations that we had not the courage to yield to. Youth! Youth! There is absolutely nothing in the world but youth!" (...) He looked round, and saw the knife that had stabbed Basil Hallward. He had cleaned it many times, till there was no stain left upon it. It was bright, and glistened. As it had killed the painter, so it would kill the painter's work, and all that that meant. It would kill the past, and when that was dead he would be free. It would kill this monstrous soul-life, and, without its hideous warnings, he would be at peace. He seized the thing, and stabbed the picture with it. There was a cry heard, and a crash. The cry was so horrible in its agony that the frightened servants woke, and crept out of their rooms. Two gentlemen, who were passing in the Square below, stopped, and looked up at the great house. They walked on till they met a policeman, and brought him back. The man rang the bell several times, but there was no answer. Except for a light in one of the top windows, the house was all dark. After a time, he went away and stood in an adjoining portico and watched. ,,Whose house is that, constable?" asked the elder of the two gentlemen. ,,Mr Dorian Gray's, sir," answered the policeman. They looked at each other, as they walked away, and sneered. One of them was Sir Henry Ashton's uncle. Inside, in the servants' part of the house, the half-clad domestics were talking in low whispers to each other. Old Mrs Leaf was crying and wringing her hands. Francis was as pale as death. After about a quarter of an hour, he got the coachman and one of the footmen and crept upstairs. They knocked, but there was no reply. They called out. Everything was still. Finally, after vainly trying to force the door, they got on the roof, and dropped down on to the balcony. The windows yielded easily: their bolts were old. When they entered they found, hanging upon the wall, a splendid portrait of their master as they had last seen him, in all the wonder of his exquisite youth and beauty. Lying on the floor was a dead man, in evening dress, with a knife in his heart. He was withered, wrinkled, and loathsome of visage. It was not till they had examined the rings that they recognized who it was. Oscar Wilde: The Picture of Dorian Gray. London 1985, S.10-11, S. 27-246. Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Liens utiles

- GRAY Dorian. Personnage du roman d’Oscar Wilde le Portrait de Dorian Gray

- PORTRAIT DE DORIAN GRAY (Le) Oscar Wilde (résumé et analyse de l’oeuvre)

- Oscar Wilde (Sprache & Litteratur).

- Portrait de Dorian Gray, le [Oscar Wilde] - fiche de lecture.

- A la fin du xixe siècle, Oscar Wilde écrivait dans la préface au Portrait de Dorian Gray : « L'appellation de livre moral ou immoral ne répond à rien. Un livre est bien écrit ou mal écrit. Et c'est tout. [...] L'artiste peut tout exprimer. » le Portrait de Dorian Gray, traduction Jaloux-Frapereau, Stock, 1925, p. 10. A l'aide d'exemples précis, et sans vous limiter forcément à la littérature, vous commenterez et discuterez cette opinion. ?