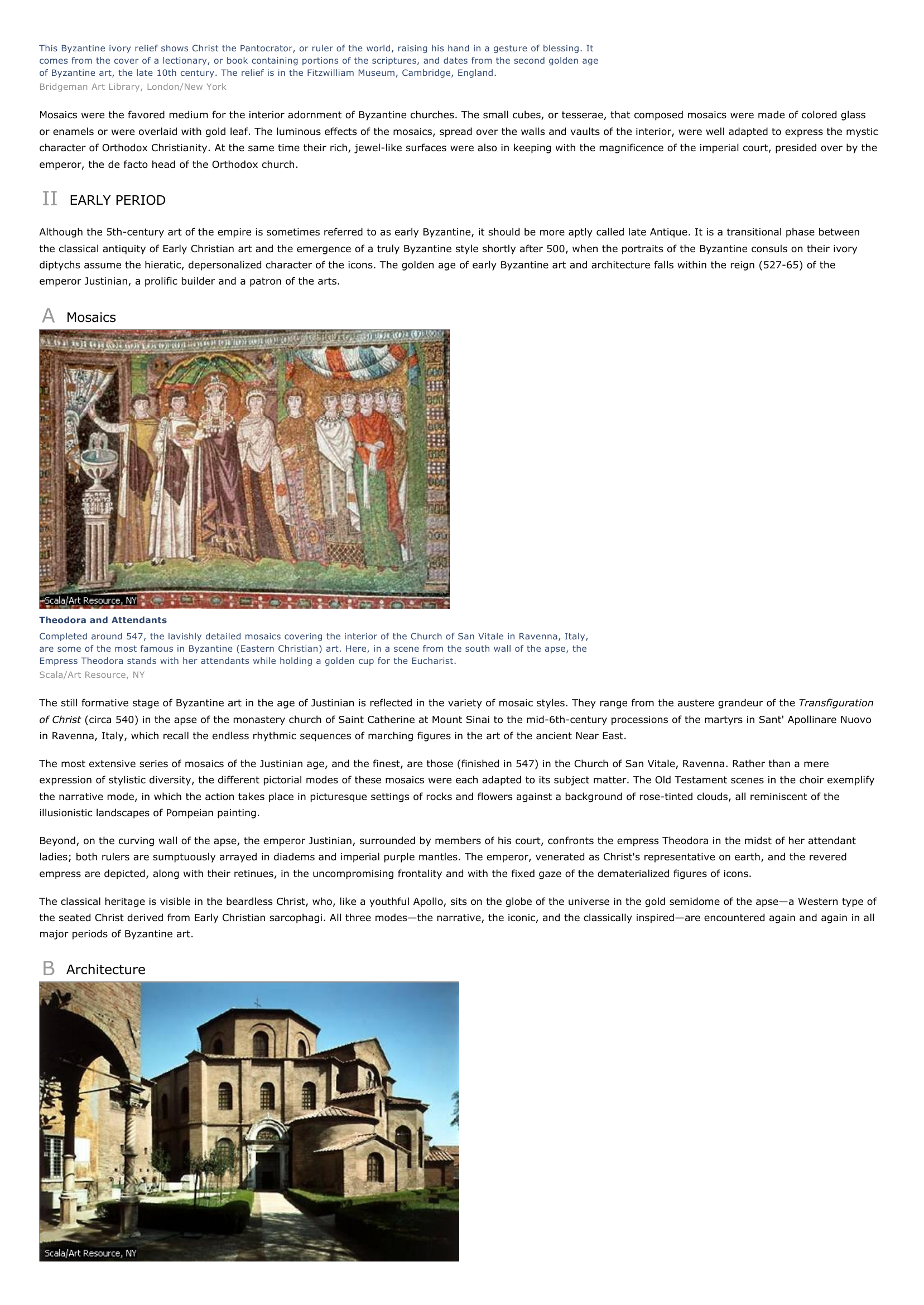

Byzantine Art and Architecture I INTRODUCTION Archangel Michael This depiction of the archangel Michael, in Saint Mark's Cathedral in Venice, Italy, is an example of ancient enamel art. During the Byzantine era artists often used precious stones for ornamentation, as seen here. Scala/Art Resource, NY Byzantine Art and Architecture, the art of the Byzantine, or Eastern Roman, Empire. It originated chiefly in Constantinople (present-day ?stanbul), the ancient Greek town of Byzantium, which the Roman emperor Constantine the Great chose in AD330 as his new capital and named for himself. The Byzantine Empire continued for almost 1000 years after the collapse of the Western Empire in 476. Byzantine art eventually spread throughout most of the Mediterranean world and eastward to Armenia. Although the conquering Ottomans in the 15th century destroyed much in Constantinople itself, sufficient material survives elsewhere to permit an appreciative understanding of Byzantine art. Byzantine art and architecture arose in part as a response to the needs of the Eastern, or Orthodox, church. Unlike the Western church, in which the popular veneration of the relics of the saints continued unabated from early Christian times throughout the later Middle Ages, the Eastern church preferred a more contemplative form of popular worship focused on the veneration of icons (see Icon). These were portraits of sacred personages, often rendered in a strictly frontal view and in a highly conceptual and stylized manner. Although any type of pictorial representation--a wall painting or a mosaic, for instance--could serve as an icon, it generally took the form of a small painted panel. Something of the abstract quality of the icons entered into much of Byzantine art. The artistic antecedents of the iconic mode can be traced back to Mesopotamia and the hinterlands of Syria and Egypt, where, since the 3rd century AD, the rigid and hieratic (strictly ritualized) art of the ancient Orient was revived in the Jewish and pagan murals of the remote Roman outpost of Dura Europos on the Euphrates and in the Christian frescoes of the early monasteries in Upper Egypt. In the two major cities of these regions, Antioch and Alexandria, however, the more naturalistic (Hellenistic) phase of Greek art also survived right through the reign of Constantine. In Italy, Roman painting, as practiced at Pompeii and in Rome itself, was also imbued with the Hellenistic spirit. The Hellenistic heritage was never entirely lost to Byzantine art but continued to be a source of inspiration and renewal. In this process, however, the classical idiom was drastically modified in order to express the transcendental character of the Orthodox faith. Early Christian art of the 3rd and 4th centuries had simply taken over the style and forms of classical paganism. The most typical form of classical art was the freestanding statue, which emphasized a tangible physical presence. With the triumph of Christianity, artists sought to evoke the spiritual character of sacred figures rather than their bodily substance. Painters and mosaicists often avoided any modeling of the figures whatsoever in order to eliminate any suggestion of a tangible human form, and the production of statuary was almost completely abandoned after the 5th century. Sculpture was largely confined to ivory plaques (called diptychs) in low relief, which minimized sculpturesque effects. Christ Pantocrator This Byzantine ivory relief shows Christ the Pantocrator, or ruler of the world, raising his hand in a gesture of blessing. It comes from the cover of a lectionary, or book containing portions of the scriptures, and dates from the second golden age of Byzantine art, the late 10th century. The relief is in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Mosaics were the favored medium for the interior adornment of Byzantine churches. The small cubes, or tesserae, that composed mosaics were made of colored glass or enamels or were overlaid with gold leaf. The luminous effects of the mosaics, spread over the walls and vaults of the interior, were well adapted to express the mystic character of Orthodox Christianity. At the same time their rich, jewel-like surfaces were also in keeping with the magnificence of the imperial court, presided over by the emperor, the de facto head of the Orthodox church. II EARLY PERIOD Although the 5th-century art of the empire is sometimes referred to as early Byzantine, it should be more aptly called late Antique. It is a transitional phase between the classical antiquity of Early Christian art and the emergence of a truly Byzantine style shortly after 500, when the portraits of the Byzantine consuls on their ivory diptychs assume the hieratic, depersonalized character of the icons. The golden age of early Byzantine art and architecture falls within the reign (527-65) of the emperor Justinian, a prolific builder and a patron of the arts. A Mosaics Theodora and Attendants Completed around 547, the lavishly detailed mosaics covering the interior of the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, are some of the most famous in Byzantine (Eastern Christian) art. Here, in a scene from the south wall of the apse, the Empress Theodora stands with her attendants while holding a golden cup for the Eucharist. Scala/Art Resource, NY The still formative stage of Byzantine art in the age of Justinian is reflected in the variety of mosaic styles. They range from the austere grandeur of the Transfiguration of Christ (circa 540) in the apse of the monastery church of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai to the mid-6th-century processions of the martyrs in Sant' Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy, which recall the endless rhythmic sequences of marching figures in the art of the ancient Near East. The most extensive series of mosaics of the Justinian age, and the finest, are those (finished in 547) in the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna. Rather than a mere expression of stylistic diversity, the different pictorial modes of these mosaics were each adapted to its subject matter. The Old Testament scenes in the choir exemplify the narrative mode, in which the action takes place in picturesque settings of rocks and flowers against a background of rose-tinted clouds, all reminiscent of the illusionistic landscapes of Pompeian painting. Beyond, on the curving wall of the apse, the emperor Justinian, surrounded by members of his court, confronts the empress Theodora in the midst of her attendant ladies; both rulers are sumptuously arrayed in diadems and imperial purple mantles. The emperor, venerated as Christ's representative on earth, and the revered empress are depicted, along with their retinues, in the uncompromising frontality and with the fixed gaze of the dematerialized figures of icons. The classical heritage is visible in the beardless Christ, who, like a youthful Apollo, sits on the globe of the universe in the gold semidome of the apse--a Western type of the seated Christ derived from Early Christian sarcophagi. All three modes--the narrative, the iconic, and the classically inspired--are encountered again and again in all major periods of Byzantine art. B Architecture Church of San Vitale, Italy Built between ad 526 and 547, the church of San Vitale stands as one of the finest examples of Byzantine architecture. Emperor Justinian I, ruler of the Byzantine Empire from 527 to 565, built San Vitale in his Italian stronghold at Ravenna when he extended Byzantine rule through western Europe. The church's design, especially its domed, centralized, octagonal core, drew heavily from earlier Byzantine architecture in Constantinople, the capital of the empire. Beautiful mosaics within the church commemorate various spiritual and secular subjects, including Justinian and the rest of the Byzantine court. Scala/Art Resource, NY As in art, a wide diversity characterizes the ecclesiastical architecture of the early Byzantine period. Two major types of churches, however, can be distinguished: the basilica type, with a long colonnaded nave covered by a wooden roof and terminating in a semicircular apse; and the vaulted centralized church, with its separate components gathered under a central dome. The second type was dominant throughout the Byzantine period. Hagia Sophia, ? stanbul Hagia Sophia (Church of the Holy Wisdom) was built in Constantinople (now ? stanbul) between 532 and 537 under the auspices of Emperor Justinian I. Innovative Byzantine technology allowed architects Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus to design a basilica with an immense dome over an open, square space, pictured. The original dome fell after an earthquake and was replaced in 563. The church became a mosque after the Ottoman conquest of 1453, and is now a museum. Roland and Sabrina Michaud/Woodfin Camp and Associates, Inc. Hagia Sophia, or the Church of the Holy Wisdom, in Constantinople, built in five years by Justinian and consecrated in 537, is the supreme example of the centralized type. Although the unadorned exterior masses of Hagia Sophia build up to an imposing pyramidal complex, as in all Byzantine churches it is the interior that counts. In Hagia Sophia the architects Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus created one of the great interior spaces in the history of architecture. The vast central dome, which rises some 56 m (185 ft) from the pavement, is dramatically poised over a circle of light radiating from the cornea of windows at its base. Four curved or spherical triangles, called pendentives, support its rim and are in turn locked into the corners of a square formed by four huge arches. The transition between the circular dome and its square base, achieved through the use of pendentives, was a major contribution of Byzantine builders to the development of architecture. To the east a vast semidome surmounts the three large vaulted niches of the sanctuary below. Arcades that recall the arcaded naves of the basilica churches occupy the ground story on the north and south sides of the central square. To the west is another huge semidome preceding a barrel-vaulted narthex. The Cattolica, Calabria Calabria in southern Italy was once the refuge of Byzantine monks and today is home to numerous buildings designed in the shape of a cross, in the traditional style of Byzantine churches. One of the more notable churches, restored in the 19th century, is the Cattolica, which dominates the town of Stilo in Calabria. The little church, with three apses and five cupolas (domes), is shown here, set against a Mediterranean landscape. John Heseltine/Corbis The ethereal quality of this "hanging architecture," in which the supports--visible on the exterior as four immense buttress towers--of the dome, pendentives, and semidomes are effectively disguised, is reinforced by the shimmering mosaics and sheets of polished marble that sheathe the interior walls and arches. III ICONOCLASTIC PERIOD Along with an appreciation of religious works of art, a strong bias had always existed among some members of the Eastern church against any depiction whatsoever of sacred scenes and personages. This antiiconic movement resulted in 726 in the order of Emperor Leo III for the destruction throughout the empire (Italy resisted) not only of icons, but of all representatives of the human figure in religious art of any kind (see Iconoclasm). During the ensuing iconoclastic period, however, the decorative arts flourished. Some idea of their character may be gained from the work of indigenous Byzantine mosaicists who created rich acanthus scrolls in the Dome of the Rock (685-705) at Jerusalem and delightful landscapes with feathery trees in the Great Mosque in Damascus (706-15). From the iconoclastic period date the oldest surviving examples of Byzantine silk textiles, some with motifs inspired by earlier Persian designs. Imported from the East, these Byzantine textiles were used in Western churches as altar hangings and as shrouds in the tombs of rulers and saints. IV MID-BYZANTINE PERIOD: MACEDONIAN RENAISSANCE In 843 the ban against icons was finally lifted, and a second golden age of Byzantine art, the mid-Byzantine period, was inaugurated with the advent of the new Macedonian dynasty (867-1056). During this appropriately named Macedonian Renaissance, Byzantine art was reanimated by an important classical revival, exemplified by a few illuminated manuscripts that have survived from the 9th and 10th centuries. As models for the full-page illustrations, the artists chose manuscripts (now lost) from the late Antique period that were illustrated in a fully developed Hellenistic style. A Painting Basil II Emperor from 976 to 1025, Basil II expanded the Byzantine Empire's borders east into Armenia and west into Bulgaria. In this 11th-century miniature from the Psalter of Basil II (Marciana Library, Venice), the emperor is shown as defender of the Christian faith, crowned by Christ and the archangel Gabriel. Bulgarian nobles kneel at his feet. Scala/Art Resource, NY In studying their prototypes the Byzantine artists learned anew the classical conventions for depicting the clothed figure, in which the drapery clings to the body, thus revealing the forms beneath--the so-called damp-fold style. They also wanted to include modeling in light and shade, which not only produces the illusion of threedimensionality but also lends animation to the painted surfaces. Religious images, however, were only acceptable as long as the human figure was not represented as an actual bodily presence. The artists solved the problem by abstraction, that is, by rendering the darks, halftones, and lights as clearly differentiated patterns or as a network of lines on a flat surface, thus preserving the visual interest of the figure while avoiding any actual modeling and with it the semblance of corporeality. Thus were established those conventions for representing the human figure that endured for the remaining centuries of Byzantine art. B Architecture In contrast to the artistic experimentations in the Justinian age, the mid-Byzantine period was one of consolidation. Recurring types of the centralized church were established, and the program of their mosaic decoration was systematized in order to conform to Orthodox beliefs and practices. A common type of the mid-Byzantine centralized church was the cross-in-the-square. As at Hagia Sophia, its most prominent feature was the central dome over a square area, from which now radiated the four equal arms of a cross. The dome was usually supported, however, not by pendentives but by squinches (small arches) set diagonally in the corners of the square. The lowest portions of the interior were confined to the small areas that lay between the arms of the cross and the large square within which the whole church was contained. C Mosaic and Enamel Crown of St. Stephen This crown was worn by Stephen I, the first king of Hungary, in the 11th century. The helmet-style crown is made of gold and set with pearls and other gems. It is especially notable for its detailed enamel work, called cloissonné, in which thin partitions of gold create separate areas that are filled with powdered enamel and then fired. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York From the fragmentary mosaic cycles in Hosios Lukas, Daphni, and several other 11th-century churches in Greece, the typical decorative program of the cross-in-thesquare church can be readily reconstructed. The program was based on the hierarchical importance of the subjects disposed in an ascending scale. The lesser saints were relegated to the lowest and least conspicuous areas of the interior. The more important saints were placed on the more essential structural elements. On the larger wall surfaces and on the higher levels beneath the dome were scenes from the Gospels and from the life of the Virgin Mary. The heavenly themes, such as the ascension, were depicted on the vaults. Pentecost, represented by energizing rays descending on the heads of the apostles, occupied the vault over the eastern arm. Beyond, in the center of the golden conch (semidome) of the apse, the Virgin bearing the Christ child reigned in isolated splendor. From the lofty center of the dome a huge bust of the bearded Christ, the Pantocrator, the awesome ruler of the universe, gazed down upon the created world below. The church thus became a symbol of the cosmos, and the whole interior, with its hierarchy of sacred images, was transformed into a vast three-dimensional icon. On a smaller scale were works in cloisonné enamel, a technique in which Byzantine artisans were highly skilled (see Enamel). Surviving examples include a few Byzantine crowns (among them the famous crown of St. Stephen of Hungary) and a number of sumptuous reliquaries. The Byzantines also fashioned other magnificent liturgical objects of silver and gold. V MID-BYZANTINE PERIOD: COMNENIAN ART Apse Mosaic, Monreale This mosaic from the royal church of Monreale, Sicily (late 12th century) was designed for the apse. The subject is Christ as the Pantocrator, with the Virgin, angels, and saints surrounding him. The mosaic was part of King Roger's effort to import the glory of Byzantium to Sicily as a symbol of his power. Scala/Art Resource, NY The second major phase of the mid-Byzantine period coincided with the rule of the Comneni dynasty (1081-1185) of emperors. Comnenian art inaugurated new artistic trends that continued into the succeeding centuries. A humanistic approach alien to earlier Byzantine art informs the icon Virgin of Vladimir (circa 1125, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow). Instead of showing her customary aloofness, the Virgin Mary here presses her cheek against that of her child in an embrace. Comnenian humanism is again encountered in the new theme of the Threnos, the lamentation over the dead body of Christ, rendered with intense pathos in a fresco of 1164 in the church of Nezerine in Croatia. Like the Virgin of Vladimir, the fresco was the work of a Constantinople painter. The most extensive series of Comnenian mosaics are those created by Byzantine artists in the large church at Monreale in Sicily, begun in 1174. The mosaic program, however, had to be readapted to the basilica form of the interior. Following a Western precedent, scenes from the Book of Genesis occupy the areas between and above the arches of the long nave arcade. The Sacrifice of Isaac, Rebecca at the Well, and Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, all masterpieces of a new dynamic narrative style, are skillfully adapted to the format of the undulating frieze that continues around and above the arches. Above, in the vast semidome of the apse, looms a gigantic bust of the Pantocrator. The Sicilian mosaics are but one example among many of the exportation of mid-Byzantine art to regions beyond the much-reduced confines of the empire. Some Byzantine influence can also be detected in the domed churches of western France. During the 11th and 12th centuries Byzantine art and architecture were the norm in the Venetian Republic. The five-domed Church of Saint Mark's (begun c. 1063) was modeled in part on Justinian's cruciform Church of the Apostles in Constantinople. In the Cathedral of Torcello the great panorama of the Last Judgment on the western wall and the lovely standing figure of the Virgin in the apsidal conch are genuine Byzantine creations. The Byzantine style was introduced into Russia in the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia at Kyiv, founded in 1037. The pervasive influence of Byzantine art on Western Europe continued into the 13th century. In the East, however, the mid-Byzantine period came to an abrupt, shocking end in 1204 with the sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders. VI PALAEOLOGUE PERIOD A brief interlude of Western rulers in Constantinople was succeeded in 1261 by the last Byzantine dynasty, that of the Palaeologan emperors (1258-1453). The final flowering of Byzantine art occurred during the Palaeologue period, and its vitality and creativeness remained undiminished. A Architecture The new architectural features had already been foreshadowed under the Comneni. In general, the vertical lines of the churches were emphasized, and the five-domed church became the norm. The drums, or circular rings on which the domes rest, often assumed octagonal form and grew taller. The domes themselves were sometimes reduced to small cupolas. Special attention was also given to exterior embellishment. B Painting and Mosaic Smallpox Mosaic, 14th Century A mosaic from the early 14th century shows a man infected with smallpox, a once-common disease that killed millions during the Middle Ages. The mosaic is located inside Kariye Mosque, also known as Church of Christ the Savior in Chora, in ? stanbul, Turkey. Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY More profound were the changes in the pictorial arts. With few exceptions, notably the splendid mosaics of the Church of Christ the Savior in Chora (1310-1320) in Constantinople, fresco painting everywhere replaced the more costly medium of mosaic decoration. The rules governing the hierarchical program of the mid-Byzantine churches were also largely abandoned. Narrative scenes sometimes occupied the vaults, and the figures tended to diminish in size, resulting in a new emphasis on the landscapes and architectural backgrounds. In the mosaics of the Church of Christ the Savior in Chora fantastic architectural forms reminiscent of modern cubism were carefully coordinated with the figures. In a contemporary fresco of the nativity in the Greek Church of the Peribleptos at Mistra, a vast rocky wasteland poignantly emphasizes the isolation of the small figures of the Virgin Mary and her child. In the background of the Raising of Lazarus in the Church of the Pantanassa at Mistra (1428), a wide V-shaped cleft between two tall peaks is eloquent of the chasm of death that separates the mummified corpse of Lazarus from the living Savior. In emphasizing the settings, however, the artists were careful to avoid any sense of actual space that might destroy the spiritual character of the scenes. Although the basic compositions of the more traditional images were retained, they were reinterpreted with exceptional vitality. In a fresco in the mortuary chapel adjoining the Church of Christ the Savior in Chora the time-honored theme of the Anastasis, the descent of Christ into limbo, was infused with extraordinary energy: The resurrected Christ strides victoriously across the shattered gates of hell to liberate Adam and Eve from the infernal regions. The Koimesis, the death and assumption of the Virgin Mary, was traditionally depicted in terms of a simple but effective arrangement: The horizontal corpse of the Virgin on her deathbed is counterbalanced by the central upright figure of Christ holding aloft the small image of her soul. In the Serbian church at Sopo?ani (circa 1265) this basic composition of the Virgin and Christ is greatly amplified to include a whole cohort of angels who are arranged in a semicircle around the figure of Christ. Transfiguration of Christ by Theophanes the Greek This icon by Byzantine painter Theophanes the Greek dates from the end of the 14th century. It represents the transfiguration of Jesus Christ, an event that is believed to have taken place on Mount Tabor. The triangular composition of the painting is emphasized by the rays of glory, which radiate from the figure of Christ down toward the three apostles. On Jesus's left is Moses (holding a tablet), and on his right is the prophet Elijah. Archivo Iconografico, S.A./Corbis These are but a few highlights of a vigorous and creative art that continued in the Balkans right into the middle of the 15th century. By that time, however, the days of Constantinople's glory were long past. Harassed by the Ottomans, the impoverished empire was reduced to little more than the city itself. In 1453 the end came with the taking of Constantinople by Muhammad II. Nevertheless, a long afterlife was granted the art and architecture of the vanished empire. Hagia Sophia provided the model for the new mosques of Constantinople. In Russia the churches continued to be built in an exotic Slavic version of the Byzantine style. The age-old traditions of icon painting (later somewhat Westernized) were handed down for generations in Russia and other parts of the Orthodox world. See also Byzantine Empire; Church; Islamic Art and Architecture; ?stanbul; Orthodox Church. Contributed By: William M. Hinkle Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.