Encyclopedia of Philosophy: HUME'S PHILOSOPHY OF MIND

Publié le 09/01/2010

Extrait du document

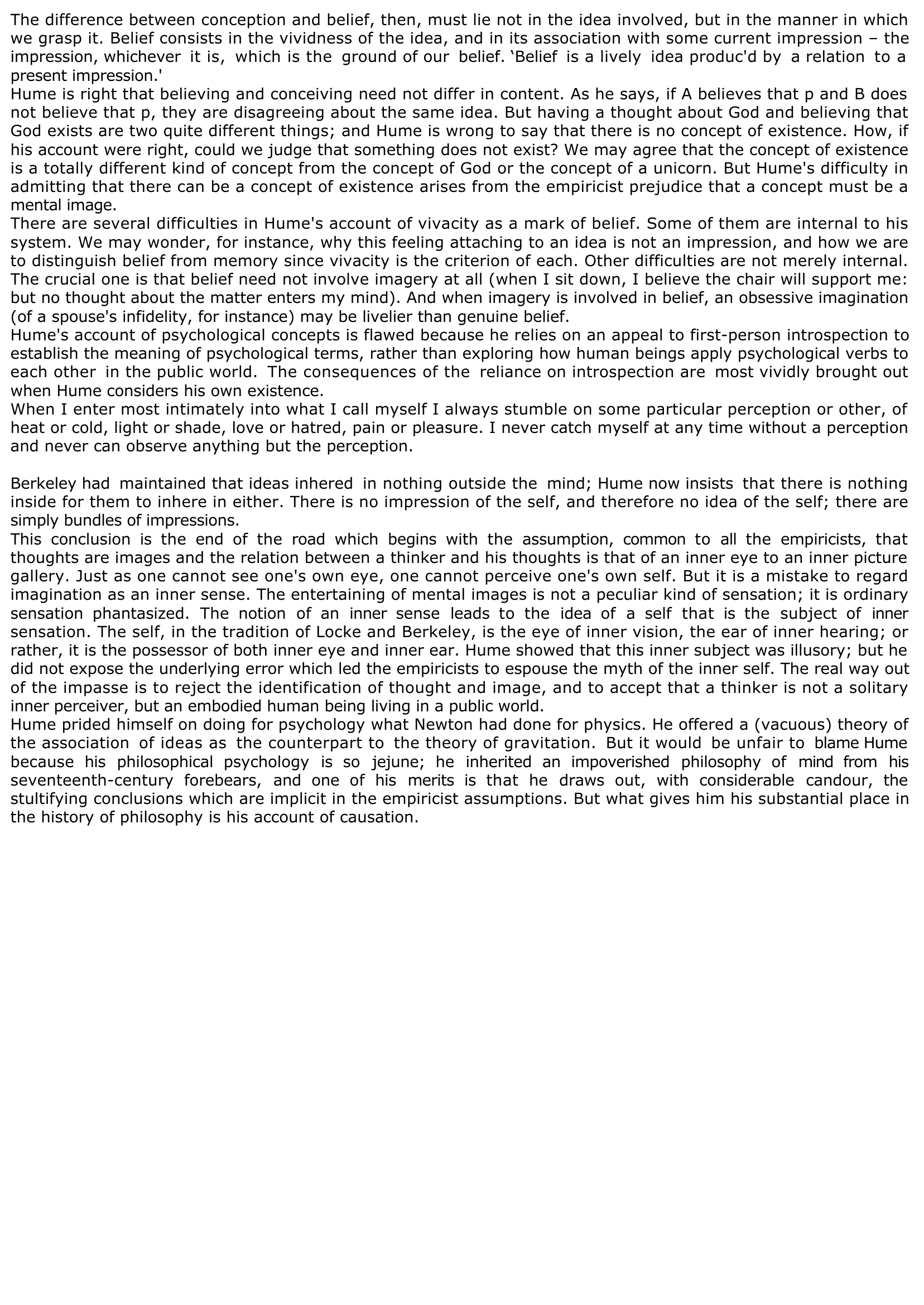

Hume was born in Edinburgh in 1711. He was a precocious philosopher, and his major work, A Treatise of Human Nature, was written in his twenties. In his own words it ‘fell dead-born from the press'; unsurprisingly, perhaps, in view of its mannered, meandering, and repetitious style. He rewrote much of its content in two more popular volumes: An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding (1748) and An Enquiry concerning the Principles of Morals (1751). He tried, and failed, to obtain a professorship in Edinburgh, and in his lifetime he was better known as a historian than as a philosopher, for between 1754 and 1761 he wrote a six-volume history of England with a strong Tory bias. In the 1760s he was secretary to the British Embassy in Paris. He was a genial man, who did his best to befriend the difficult philosopher Rousseau, and was described by the economist Adam Smith as having come as near to perfection as any human being possibly could. In his last years he wrote a philosophical attack on natural theology, Dialogues concerning Natural Religion, which was published, three years after his death, in 1776. To the disappointment of James Boswell (who recorded his final illness in detail) he died serenely, having rejected the consolations of religion.

«

The difference between conception and belief, then, must lie not in the idea involved, but in the manner in whichwe grasp it.

Belief consists in the vividness of the idea, and in its association with some current impression – theimpression, whichever it is, which is the ground of our belief.

‘Belief is a lively idea produc'd by a relation to apresent impression.'Hume is right that believing and conceiving need not differ in content.

As he says, if A believes that p and B doesnot believe that p, they are disagreeing about the same idea.

But having a thought about God and believing thatGod exists are two quite different things; and Hume is wrong to say that there is no concept of existence.

How, ifhis account were right, could we judge that something does not exist? We may agree that the concept of existenceis a totally different kind of concept from the concept of God or the concept of a unicorn.

But Hume's difficulty inadmitting that there can be a concept of existence arises from the empiricist prejudice that a concept must be amental image.There are several difficulties in Hume's account of vivacity as a mark of belief.

Some of them are internal to hissystem.

We may wonder, for instance, why this feeling attaching to an idea is not an impression, and how we areto distinguish belief from memory since vivacity is the criterion of each.

Other difficulties are not merely internal.The crucial one is that belief need not involve imagery at all (when I sit down, I believe the chair will support me:but no thought about the matter enters my mind).

And when imagery is involved in belief, an obsessive imagination(of a spouse's infidelity, for instance) may be livelier than genuine belief.Hume's account of psychological concepts is flawed because he relies on an appeal to first-person introspection toestablish the meaning of psychological terms, rather than exploring how human beings apply psychological verbs toeach other in the public world.

The consequences of the reliance on introspection are most vividly brought outwhen Hume considers his own existence.When I enter most intimately into what I call myself I always stumble on some particular perception or other, ofheat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure.

I never catch myself at any time without a perceptionand never can observe anything but the perception.

Berkeley had maintained that ideas inhered in nothing outside the mind; Hume now insists that there is nothinginside for them to inhere in either.

There is no impression of the self, and therefore no idea of the self; there aresimply bundles of impressions.This conclusion is the end of the road which begins with the assumption, common to all the empiricists, thatthoughts are images and the relation between a thinker and his thoughts is that of an inner eye to an inner picturegallery.

Just as one cannot see one's own eye, one cannot perceive one's own self.

But it is a mistake to regardimagination as an inner sense.

The entertaining of mental images is not a peculiar kind of sensation; it is ordinarysensation phantasized.

The notion of an inner sense leads to the idea of a self that is the subject of innersensation.

The self, in the tradition of Locke and Berkeley, is the eye of inner vision, the ear of inner hearing; orrather, it is the possessor of both inner eye and inner ear.

Hume showed that this inner subject was illusory; but hedid not expose the underlying error which led the empiricists to espouse the myth of the inner self.

The real way outof the impasse is to reject the identification of thought and image, and to accept that a thinker is not a solitaryinner perceiver, but an embodied human being living in a public world.Hume prided himself on doing for psychology what Newton had done for physics.

He offered a (vacuous) theory ofthe association of ideas as the counterpart to the theory of gravitation.

But it would be unfair to blame Humebecause his philosophical psychology is so jejune; he inherited an impoverished philosophy of mind from hisseventeenth-century forebears, and one of his merits is that he draws out, with considerable candour, thestultifying conclusions which are implicit in the empiricist assumptions.

But what gives him his substantial place inthe history of philosophy is his account of causation..

»

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- Encyclopedia of Philosophy: THE ESSENCE OF MIND

- Encyclopedia of Philosophy: AQUINAS' PHILOSOPHY OF MIND

- Encyclopedia of Philosophy: al-Ghazali, Abu Hamid

- Encyclopedia of Philosophy: al-Farabi, Abu Nasr

- Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Alexander, Samuel